When Alexander founded in the Nile Delta one of his many Alexandrias in 331 BCE, he would have been overjoyed to know that this settlement would later become one of the cultural capitals of the ancient world—a city that still bears his name today. This location was not entirely unknown to the Greeks. In fact, it was on the nearby island of Pharos, just across the limestone ridge where Alexandria would rise, that Homer situated the abode of Proteus, a prophetic sea god. Nor was Alexandria completely barren; the small Egyptian fishing village of Rhakotis, which would later become one of the city’s neighborhoods, was already established there. The site’s potential as a trading hub was evident from the thriving nearby ports of Canopus and Heracleion.

Researching Alexandria presents significant challenges. One major obstacle is that the city has been continuously inhabited since its founding, which severely limits opportunities for excavation. However, recent archaeological surveys and explorations of the old harbor—now submerged beneath the Mediterranean—have uncovered remarkable treasures and provided invaluable insights. For example, the discovery of several statues depicting Ptolemaic kings as pharaohs has challenged the long-held perception of Alexandria as a purely Greek-looking city. While the predominance of Greek culture is not disproven, these findings add nuance to previously accepted views. Nevertheless, much of what we know about Hellenistic Alexandria still relies heavily on literary sources, such as the writings of the geographer Strabo.

After Ptolemy I Soter gained control of Egypt following the Partition of Babylon in 323 BCE, he initially ruled briefly from Memphis before relocating with his retinue to Alexandria. Under his leadership, the city continued to grow and prosper. Alexandria was organized as a Greek polis and has often been regarded as distinct from the rest of Egypt. This distinction is notably reflected in its later Roman designation, Alexandria ad Aegyptum, meaning “Alexandria by Egypt,” rather than “in Egypt.”

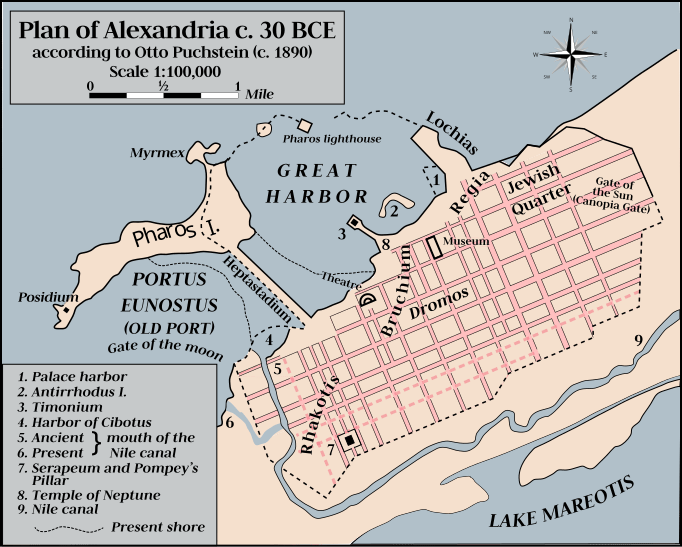

Alexandria has often been described by ancient authors as being shaped like a cloak (chlamys), stretching approximately 6 kilometers from east to west and only about 2 kilometers from north to south. The city’s neighborhoods were laid out according to an organized grid plan, a design attributed to Deinokrates of Rhodes. Historically, both scholars and the public were quick to regard this type of urban organization as an enlightened Greek invention. However, the Egyptians had been building towns in this manner for centuries. One of the defining features of Alexandria, which astonished its visitors, was its broad streets lined with numerous stoai, giving the sides of the streets the appearance of a continuous colonnade.

The city was dominated by the vast palace complex of the Ptolemies, located to the east of the Great Harbour, primarily on Cape Lochias. This grand district housed the renowned Museum and Library, the tomb of Alexander the Great, and the sepulchers of the Ptolemies, eventually united within a pyramid-shaped structure commissioned by King Ptolemy IV (r. 221–204 BCE). The palatial quarter spanned between one-third and three-quarters of the city’s area and included open spaces accessible to the public. These spaces hosted significant festivals, such as the Adonis festival, vividly described in Idyll 15 by Theocritus. Such celebrations were pivotal in nurturing a shared “Alexandrian” identity. Nearby, the Temple of Poseidon and the Theatre on Hospital Hill added to the city’s cultural and architectural splendor.

One of the most celebrated architectural projects initiated by Ptolemy I was the renowned Lighthouse on the island of Pharos, designed by Sostratos of Knidos. Over time, the lighthouse became synonymous with the island itself. However, Ptolemy I did not live to see its completion. Beyond its practical function as a beacon for seafarers, the lighthouse served as a powerful piece of state propaganda, symbolizing the might and grandeur of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Later hailed as one of the “Seven Wonders of the World,” the Lighthouse of Pharos stood as a testament to ancient engineering and ambition. Sadly, earthquakes and the subsequent reuse of its materials have reduced this once-majestic structure to little more than its foundations.

Diodoros tells us that in his time (1st century BCE), approximately 300,000 “free” inhabitants lived in Alexandria. According to Jane Rowlandson, this suggests a total population of around 500,000. Most of these inhabitants were of Greek and Macedonian descent. As vividly portrayed by Theocritus in his Idyll 15, many settlers from the Hellenic world initially retained the identity of their mother city during the 3rd century BCE. However, a study by Willy Clarysse (1998) indicates that by the 2nd century, wealthier citizens had begun to develop a distinct “Alexandrian” identity.

In addition to Greeks and Macedonians, many other ethnic groups lived in the metropolis, including Egyptians, who resided in the neighborhood of Necropolis. The hostility and racism prevalent in the city are vividly depicted in the aforementioned Idyll by Theocritus, which describes Egyptians as nothing more than thieves. Another important community in Alexandria was the Jewish population. According to tradition, it was here that the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek by 72 translators at the request of King Ptolemy II (r. 285–247 BCE). Over time, a significant portion of the Jewish community came to embrace Greek culture, in stark contrast to their northern counterparts, who fought wars to resist such assimilation.

Near the Egyptian quarter stood the Temple of Serapis, also known as the Serapeum. The temple, in its recognizable form, was constructed under Ptolemy III (r. 246–222 BCE). Serapis was a syncretic deity, arising from the combined worship of Osiris and Apis. He was often depicted in a Hellenized style, and tradition holds that Ptolemy I introduced this god to the settlers of Alexandria. The goal was to provide them with a local yet familiar deity they could relate to, in contrast to the traditional Egyptian gods, whose animal-headed forms were alien to the Greek settlers. At the same time, the Osiris and Apis elements in the cult ensured that Serapis also resonated with the local Egyptian population. Over time, Serapis became an immensely popular god, venerated throughout the entire Mediterranean.

Another focal point of Alexandria’s religious life was the dynastic cult. After their deaths, the monarchs of Egypt were venerated as gods, and festivals were held in their honor, such as the Ptolemaieia, the Arsinoeia, and the Basileia. The queens, in particular, were widely celebrated throughout the city.

The will of the Alexandrians was poorly represented in political life, with key institutions, such as the bouleuterion, wielding little power. There is also no evidence of an assembly of the people. The political arena was dominated by the royal family, and understandably so, as Alexandria served as the center of a Hellenistic kingdom. Nevertheless, the people found other ways to express their opinions on matters of public interest. In our sources, riots are frequently mentioned, such as the unrest that occurred after the murder of Arsinoe III.

Olivier Goossens

Leave a comment