Around 2000 BCE, the Indo-Europeans migrated to what is today Greece. After settling there, they lived for several centuries in the shadow of the splendorous Minoan civilization on Crete. However, the Indo-Europeans did not remain idle. They developed into a series of well-organized small states, ruled by kings (wanax) in their heavily fortified palaces. This led to the rise of the Mycenaean civilization, named after its most prominent and famous stronghold, Mycenae. After the disintegration of the Minoan civilization—partly due to the catastrophic volcanic eruption on Thera (Santorini) around 1650 BCE—it was the Mycenaeans’ turn to become the dominant power in the Aegean.

Their artifacts are found throughout the entire Mediterranean, with some of their manufactured goods even reaching Nubia.[1] This attests to the extensive trading networks of the Mycenaean states. Archaeology is our primary source of information in this area, as the Linear B tablets offer only limited evidence of Mycenaean commercial activity. However, this is not the focus of this brief article. Our aim is to explore the regions where Mycenaean presence was not simply the result of brief visits by traders, but rather the permanent settlement of large groups of Greeks—i.e., colonization.

There are three types of colonization. The first involves annexation, where a large group of immigrants takes over already occupied territory. The second is known as a “settlement colony,” where migrants establish themselves in unoccupied land. In this type of colonization, immigrants are most likely to retain their original cultural practices. The third type occurs when a large cultural group is allowed to settle in an existing town but is subjugated to local authorities. These colonies are usually established for commercial purposes. A good Bronze Age example is the Assyrian trading colony in the city of Kanesh, where the immigrants lived in a designated quarter of the city. These colonists in trading posts sometimes held a degree of autonomy over certain matters.

One methodological challenge is the lack of contemporary written sources providing information about colonization activities. To date, no word equivalent to “colonize” has been identified in Bronze Age Greek. [2]Moreover, no Linear B documents have been discovered outside the Greek mainland and Crete. Similarly, foreign texts from Mycenaean trading contacts, such as those from Ugarit, offer no relevant insights. Consequently, it appears that we are once again at the mercy of archaeology for answers.

Another potential non-material source of information is the epic tradition, though its use requires great caution. While some scholars dismiss the reliability of later literary sources, others see value in them. [3]Vanschoonwinkel argues that valuable insights can be gleaned by cross-referencing literary traditions with archaeological evidence. [4] He suggests that there is at least some truth to the stories about legendary times in Classical Greece. For instance, the reluctance of legendary heroes to visit the Levant and Egypt aligns with the lack of evidence for Mycenaean settlements in these regions. This approach gains credibility from archaeological research at Hissarlik (Troy), which uncovered evidence of a large-scale siege that could serve as the historical basis for Homer’s Iliad.

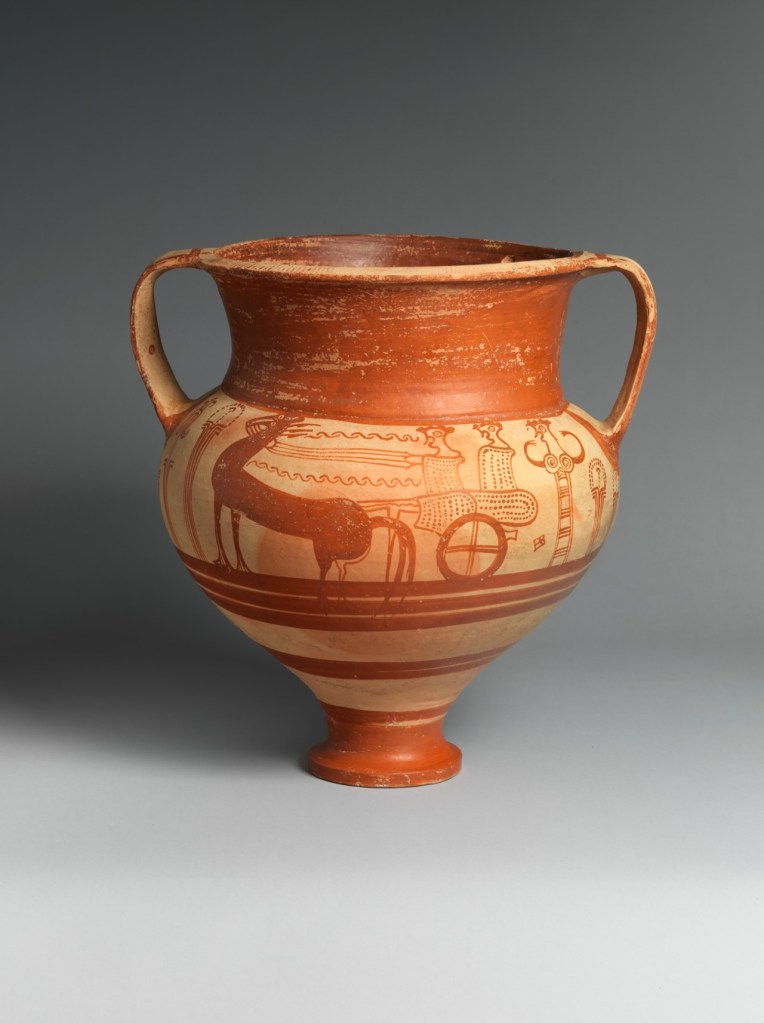

Pottery can also serve as a valuable source of information, though it can present a misleading picture. Some regions have been more thoroughly excavated than others, meaning a lack of pottery in certain areas of the Mediterranean does not necessarily indicate reduced Mycenaean presence. Similarly, a high concentration of Mycenaean ceramics does not necessarily signify colonization; it could just as easily result from successful trade conducted by the Mycenaeans.

As Vanschoonwinkel rightly observes, material evidence that cannot be easily attributed to mere trade—such as funerary practices—is particularly revealing. This aspect of human culture is deeply ingrained and rarely changes solely through commercial contact. Funerary practices similar to those of mainland Greece could, therefore, indicate the settlement of Greeks originating from the Mycenaean kingdoms.

To date, no substantial Helladic evidence has been discovered at any site that conclusively indicates Mycenaean colonization outside the Aegean.[5] While some traces suggest the presence of Mycenaean individuals or small groups, there is no evidence of large-scale migration. Some archaeologists have proposed the existence of Mycenaean trading posts in locations such as Ugarit and Tell Abu Hawam in the Levant[6], Scoglio del Tonno in southern Italy, Thapsos in North Africa, and Antigori in Sardinia.[7] However, these claims have been effectively disproven.

Excavations in Cyprus and western Anatolia have provided more compelling evidence, including the prevalence of imported Mycenaean pottery and the presence of local workshops producing similar ceramics. Even more significant is the similarity in funerary practices. The Bronze Age archaeological layers at Iasus and Miletus reveal urban centers that were either Mycenaean or heavily Mycenaeanized. Additionally, discoveries such as the necropolis at Müskebi, the tholos at Colophon, and possibly the cemetery at Panaztepe suggest the existence of more Mycenaean settlements in Asia Minor.

Textual evidence supports the idea of Mycenaean settlement on the eastern side of the Aegean. A Hittite archive contains a text detailing relations with the so-called Ahhijawa, a term likely referring to the Achaeans/Mycenaeans. [8] Initially, the Hittite term Ahhijawa described the people living along the Aegean coasts. These interactions began in the late 15th century BCE, coinciding with the earliest Mycenaean remains found at Iasus and Miletus. Moreover, the city of Millawata or Millawanda—likely Miletus—is mentioned as being within the sphere of influence of the Ahhijawa.

Cyprus presents a unique case. Greek immigration to the island began no earlier than the late 13th century and unfolded gradually. These immigrants can be definitively identified as Mycenaeans, as demonstrated by pottery and burial complexes from the 12th and 11th centuries. Interestingly, the epic tradition links the settlement of Greeks on Cyprus to events following the Fall of Troy, placing it in the later part of the legendary era—an account that is not far removed from historical reality. Over time, the growing Greek presence and local assimilation led to Cyprus being considered part of the Hellenic world.

The study of Mycenaean colonization is complicated by significant methodological challenges. No evidence has emerged to confirm settlements outside the Aegean. However, within the Aegean region—particularly along the western Anatolian coast and in Cyprus—there are indications of stronger Mycenaean influence, suggesting the possible existence of Bronze Age Greek colonies in these areas. The debate remains unresolved, and further archaeological research is needed to provide greater clarity on the subject.

Olivier Goossens

[1] Spataro, Garnett, Shapland, Spencer & Mommsen 2019, 683-697.

[2] Casevitz 1985, 221-223.

[3] Embrace: Bérard 1957; Fortin 1980; 1984.

Reject: Pearson 1975; Baurain 1989.

[4] Vanschoonwinkel 2006, 41- 113.

[5] Wace and Blegen 1939; Immerwahr 1960.

[6] Stubbings 1951, 107; Van Wijngaarden 2002, 71–3.

[7] Taylour 1958, 128; Immerwahr 1960, 8–9; Voza 1972; 1973; Bietti Sestieri

1988, 28, 37, 40; Kilian 1990, 455, 465; Jones and Vagnetti 1991, 141 (cf. Vagnetti 1993, 152); Van Wijngaarden 2002, 235–6.

[8] Bryce 1989; Vanschoonwinkel 1991, 399–404.

Leave a comment