The Indo-Europeans were a nomadic people, shrouded in mystery. Their existence was first inferred by linguists who identified numerous syntactical and lexical similarities among various languages spoken across the Eurasian continent, from the British Isles to Central Asia. As a result, generations of linguists have faced the significant challenge of reconstructing the theorized proto-language that existed several thousand years ago. Alongside these linguistic efforts, interest in the culture and identity of the people who spoke this language also grew. In this article, I aim to explore one particular aspect of the Indo-Europeans: their religion and mythology, and how comparative linguistic research can help fill the gaps in our limited source material.

Sources

Reconstructing Indo-European religion is a major challenge due to the absence of direct archaeological evidence. Several materially attested cultures have been proposed as representatives of the Indo-Europeans, but none have gained general acceptance within the academic community. As a result, our primary sources of information are language and literature. The search for common divine names and shared mythological themes has dominated scholarly research. Several schools of thought have emerged, each approaching the topic from a different perspective, though all rely on the same comparative method (cf. infra).[1]

One of the most important sources of information has, without a shadow of a doubt, been the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas. Philological and linguistic research has shown that most of the material in this text dates back to the 2nd millennium BCE, preserved through oral transmission using meticulous mnemotechnic methods.[2] Some scholars have placed significant emphasis on the Rigveda in the study of Indo-European religion. Friedrich Max Müller, for instance, came close to equating Vedic mythology with Indo-European mythology—a view that is, admittedly, quite a stretch. Interestingly, Greek literature has received comparatively less scholarly attention, largely due to the belief that many of its “pure” Indo-European elements were obscured or replaced by strong pre-Greek and Near Eastern influences.[3] Other important sources for the study of Indo-European religion include Roman, Baltic, and Norse mythology. Surprisingly, Scythian mythology has received relatively little scholarly attention, even though it is generally accepted that the Scythians remained comparatively close to the original Indo-European cultural sphere. [4] Tabiti, Papaios and Api are for example believed to have been gods of the Indo-European Pantheon.[5]

The Four Major Schools of Thought

First there is the so-called Meteorological or Naturist School. These scholars believed that Indo-European myth originated in the human urge to explain broad natural phenomena such as the sky, sun, moon, dawn … [6] The worship of these natural elements was central in their rituals. German-born British philologist and Orientalist, Friedrich Max Müller, interpreted these ancient rituals and myths primarily as solar allegories.[7]The Meteorological School, though having recently found some new proponents, has lost most its following throughout the 20th century.

The second major school is the Ritual School. Its adherents claim that the Indo-European myths were formed to explain already existing rituals.[8] This school had a more pragmatic view of the Indo-European religion, claiming that their rituals first and foremost served as attempts to manipulate nature to their own advantage.[9]Sir James George Frazer, the famed author of the Golden Bough, was a proponent of this theory.[10]Professor Bruce Lincoln of the University of Chicago has even proposed a well-defined creation myth of the human race among the Indo-Europeans: there was an original sacrifice of a man by his twin brother, the creator of the humans. The Indo-Europeans consequently reenacted this mythical event with their own sacrifices.[11]

The Functionalist School on the other hand, holds that myths served to justify existing social behaviour and to legitimize the social hierarchy.[12] The influential theory of the trifunctional system, developed by Georges Dumézil, has played a pivotal role in the development of the Functionalist School. Dumézil’s theory suggested that the religion of the Indo-Europeans reflected and upheld a typical tripartite order of society, with a priest, warrior and servants’ class. The French linguist and philologist has therefore put great emphasis on the importance and triads in ancient religions, such as the Capitoline triad Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.[13]

Finally, there is the Structuralist School which was dominant in the Soviet world.[14] Structuralists believe that the human mind understands the world through binary oppositions, and that it approaches problems by framing them in terms of opposing patterns. Moreover, the structuralists did not reject Dumézil’s tripartite system but rather refined it. They emphasized the oppositional features present within each function—for example, the creative and destructive aspects of the warrior class.[15]

Three examples of Comparative Linguistic Research for Reconstructing the Indo-European Religion

Fire

“Agni shines with powerful light; from his powers, he makes things manifest” -Rigveda 5.2.8-9-

Several deities can be identified through linguistic evidence. One such figure is Agni, a god attested in both the Rigveda and the Kushan Empire. Agni is the god of fire in all its forms: the sun, lightning, forest fires, and the domestic hearth—in short, both celestial and terrestrial fires. He is not primarily celebrated as a destructive force, however, as the cited passage makes clear. Rather, he is revered as the light of truth that unveils reality.[16]

Agni is evidently of Indo-European descent, since the word has cognates all over the Indo-European linguistic sphere. The most famous cognate for European readers is probably the Latin word for fire: ignis. Another cognate can be found in Balto-Slavic as *ungnis, which also means fire.[17] The commonly accepted reconstructed Proto-Indo-European word for fire is *h₁n̥gʷnis.

What all these cognates have in common is that they are associated with a religious cult centered around the natural element of fire. Several early modern sources report that the Lithuanians worshipped a sacred fire named Ugnis, which they kept burning eternally. The idea of maintaining a perpetual sacred flame may sound familiar to scholars of Roman history, as the flame of Vesta was similarly kept alight by a group of virgins in Ancient Rome. Meanwhile, like their Baltic neighbors, the Latvians also had a fire cult dedicated to a deity named Uguns, who functioned as a kind of mother goddess. Further to the east, Old Church Slavonic texts provide evidence that the Slavs worshipped fire, referred to as ogonĭ.[18] All these attestations of venerated fire deities—spanning a vast area from the cold Baltic north to the warm and humid Indian subcontinent—are no coincidence. Scholars believe that h₁n̥gʷnis, the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European word for ‘fire,’ referred not only to the physical element but also to a fire deity in Indo-European religion. The general consensus is that this god was associated with the hearth, serving as a domestic or sacrificial deity central to communal and ritual life.[19] Martin West states that this sacred fire was venerated and carefully maintained by the household, and that it was even transported intact when a family moved to a new dwelling.[20] While this idea highlights the fire’s central ritual significance, it does raise questions about its practicality—especially in the context of a nomadic society, where constant movement would make the preservation of a continuous flame highly impractical.

Dyaus Pitā – Jupiter

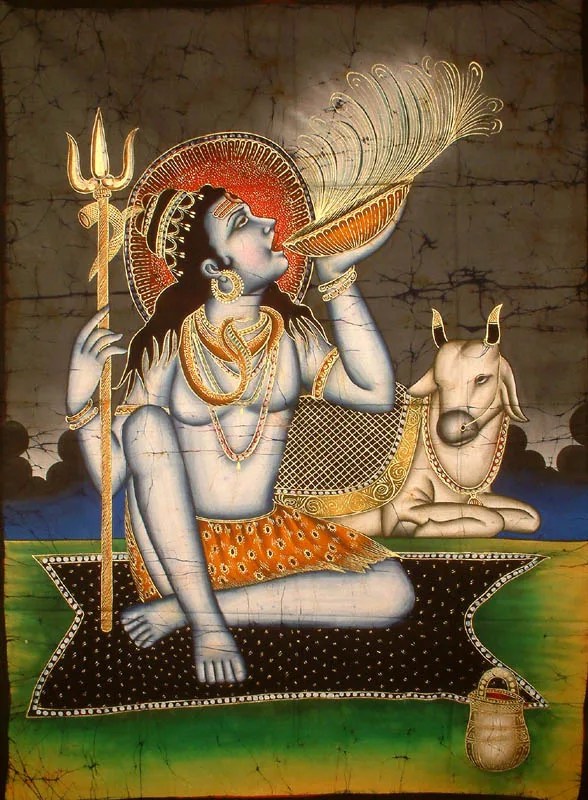

Another deity found in the Rigveda that may sound quite familiar to scholars of classical antiquity is Dyaus Pitā (द्यौष्पितृ). An immediate resemblance to the name of the Roman supreme deity, Jupiter, is evident. The Greek god Zeus is also a cognate of the element Dyaus. All these gods share a common association with the sky. However, while Zeus and Jupiter were both elevated to the position of supreme god within their respective pantheons, Dyaus Pitā did not enjoy the same prominence. Over time, he faded into obscurity within Brahmanism.

Dyaus derives from the Indo-Iranian *dyā́wš, which in turn is believed to originate from the Proto-Indo-European *dyēus. It is generally accepted that this *dyēus functioned as the sky god of the Indo-Europeans. Similar to Dyaus Pitā, *dyēus‘ name was likely often combined with the Proto-Indo-European word for father, *ph₂tḗr, signaling the Indo-Europeans’ conception of the deity as a father figure. The *ph₂tḗr element later faded in Greek, where the supreme god was conventionally referred to simply as Zeus, though in some literary contexts, he occasionally reappears as Zeus Patēr (Ζεὺς πατὴρ). The Romans, however, preserved this combination. In Old Latin, the Romans invoked the deity using the vocative compound Iou and pater, rather than the nominative Ious. According to some linguists, this Latin form derives from the Proto-Italic Djous Patēr.[21]

Soma

The ancient Indo-Europeans supposedly had a sacred drink: fermented honey. According to Witzel, this potion eventually evolved into a more bitter beverage in the western part of Central Asia, which became the Vedic soma or Avestan haoma. These cognates derive from the Indo-Iranian root *sav-, meaning “to press,” referring to the act of pressing the stalks of a plant.[22] Manfred Mayrhofer has suggested a Proto-Indo-European origin in the root *sew(h)-.[23] Witzel supports a Proto-Indo-European background for the word soma, as opposed to an origin in the Bactria–Margiana Culture (BMAC).[24]

In the ancient Vedic literature, soma was a potion that granted eternal life to the gods, with Indra and Agni depicted as consuming it in great quantities.[25] It also bestowed supernatural strength, as illustrated in the myth of Indra drinking soma before his battle with the demon Vritra. In Vedic India, an elaborate ritual accompanied the preparation of soma, as described in the Soma Mandala. This ritual involved pressing and straining the soma plant and mixing it with water or milk. Each act in the ritual was imbued with symbolic meaning, as reflected in the hymns. Soma is also personified as a deity, with a central myth recounting his liberation by a falcon from captivity under the archer Kṛśānu. He was then brought to Manu, the first man and sacrificer.

In Iran, haoma features in the religious literature of the Zoroastrians, the Avesta.[26] The word haoma of the Avestan language survived into Old Persian as hauma (𐏃𐎢𐎶) in the DNa inscription (c. 490 BCE) at Naqsh-e Rostam. Hauma then morphed into hōm () in Middle Persian and is still in use today as a name in Iran (هوم). The divine plant is described in the Avestan texts as tall, fragrant, and golden green.[27] It was said to have the power to heal, stimulate sexual arousal, strengthen physically, and was “nutritious for the soul”.[28]

The drink is still prepared today by Brahmins in South India, Zoroastrians in Yazd and Kerman in Iran, and by the Parsi community in Mumbai. Interestingly, the writer Aldous Huxley was inspired by Vedic literature when he named the sedative drug in his dystopian novel Brave New World “soma.” Ironically, unlike the Vedic soma, which was associated with immortality and divine power, Huxley’s soma served to dull emotion and suppress individuality—offering superficial happiness at the cost of personal freedom and a shortened life.

A synonym for soma in the Rigvedic texts is amṛta (अमृत), which is etymologically related to the Greek ambrosia and literally means “immortality.” These cognates derive from the Proto-Indo-European word *ṇ-mṛ-tós.[29] The negative prefix *n- evolved into a- in both Greek and Sanskrit, while *mṛ is the zero-grade form of *mer-, meaning “to die.” Just as in Vedic culture, ancient Greek ambrosia was considered the food or drink that granted eternal life to the gods. According to Homer, ambrosia was brought to Mount Olympus by doves and was served either by Zeus’ lover Ganymede, the goddess of youth Hebe, or Dionysus’ nurse, Ambrosia. [30]

Conclusion

The three examples above demonstrate that we can reconstruct the religious worldview of the Indo-Europeans to a certain extent. However, as is the case with all Indo-European studies, there is always room for refinement or even outright refutation of the proposed theses. Unless concrete archaeological evidence emerges, we are left with linguistic traces in the various civilizations that arose from the Indo-European wanderers of the Eurasian steppes. This does not mean, however, that comparative linguistic research has been unfruitful. It has, for example, revealed that the Indo-Europeans were a people who saw divinity in natural elements like the sky and fire, and who used a plant-based potion during rituals, to which they ascribed magical powers.

Olivier Goossens

Bibliography

–Anthony, D., The Horse, The Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, 2007, Princeton.

–Beckwith, C., Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present, 2011, Princeton.

–Derksen, R., Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, 2008.

-De Vaan, M., Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages, 2018, Leiden-Boston.

–Divino, F., “Seers and Ascetics: Analyzing the Vedic Theory of Cognition and Contemplative Practice in the Development of Early Buddhist Meditation and Imaginary”, Religions, Vol. 16, pp. 378-433.

–Dumézil, G., Mythe et épopée: L’idéologie des trois fonctions dans les épopées des peuples indo-européens, 1986.

–Flood, G., An Introduction to Hinduism, 1996, Cambridge.

–Geldner, K., Der Rig-Veda, Vol. 3, 1951, Cambridge (MA).

–Jakobson, R., “Linguistic Evidence in Comparative Mythology”, Roman Jakobson: Selected Writings, ed. S. Rudy, 1985, pp. 12-32.

–Mallory, J. & Adams, D., The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, 2006, Oxford.

–Mallory, J. & Adams, D., Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, 1997, London.

–Mayrhofer, M., Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen, Vol. 2, 1992, Heidelberg.

–Puhvel, J., Comparative Mythology, 1987, Baltimore.

–West, M., Indo-European Poetry and Myth, 2007, Oxford.

–Witzel, M., “Beyond the Flight of the Falcon”, Which of Us are Aryans? Rethinking the Concept of Our Origins, ed. R. Thapar, 2019, New Dehli, pp. 1-29.

–Woodard, R., Indo-European Sacred Space: Vedic and Roman Cult, 2006, Illinois.

[1] Mallory & Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, 427-431.

[2] Flood, An Introduction to Hinduism, 37; Anthony, The Horse, The Wheel and Language, 454; Witzel, “Beyond the Flight of the Falcon”, 11.

[3] Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 138, 143.

[4] Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel, and Language.

[5] West, Indo-European Poetry and Myth, 266.

[6] Mallory & Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, 116

[7] Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 13–15.

[8] Mallory & Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, 428–429; Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 14–15.

[9] Mallory & Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, 116.

[10] Puhvel, Comparative Mythology, 15.

[11] Mallory & Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, 428–429.

[12] Mallory & Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, 116.

[13] Dumézil, Mythe et épopée.

[14] Mallory & Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World, 431.

[15] Idem.

[16] Divino, “Seers and Ascetics”, 9.

[17] Derksen, Etymological Dictionary of the Slavic Inherited Lexicon, 364.

[18] Jakobson, “Linguistic Evidence in Comparative Mythology”, 26.

[19] West, Indo-European Poetry and Myth, 269.

[20] Idem.

[21] De Vaan, Etymological Dictionary of Latin and the other Italic Languages, 315.

[22] Geldner, Der Rig-Veda, Vol. 3, 1-9.

[23] Mayrhofer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen, Vol. 2, 748.

[24] Beckwith, Empires of the Silk Road, 32; Anthony, The Horse, the Wheel and Language, 454-455.

[25] Amrita, Rigveda 8.48.3.

[26] Hōm Yast, Yasna 9

[27] Tall: Yasna 10.21, Vendidad 19.19; fragrant Yasna 10.4; golden green: Yasna 9.16.

[28] Healing: Yasna 9.16-17, 9.19, 10.8, 10.9; sexual arousal: Yasna 9.13-15, 9.22; strengthen: Yasna 9.17, 9.22, 9.27; nutritious for the soul: Yasna 9.16.

[29] Mallory, “Sacred Drink”, 538.

[30] Homer, Odyssey, 12.62-63: “πέλειαι / τρήρωνες, ταί τ᾽ ἀμβροσίην Διὶ πατρὶ φέρουσιν”; Cicero, De Natura Deorum, 1.40.

Leave a comment