A Study of Indo-Central Asian Polities in the Age of Silk Roads in the twelfth century

As the hooves of the nomadic horses thundered from across the Steppes, the traders and mystics hummed in the bazaars of Delhi and Samarkand alike. Two worlds—Hindustan (historical name for medieval northern India) and Central Asia (or the Khorasan and Mawara’ al-Nahr/Transoxiana, to be specific)—found themselves drawing closer towards one another. The pull cast by entities both material and abstract. In the twelfth century, the Silk Road did not just ferry silk, horses, spices, or slaves; but also, ideas, doctrines, vocabularies and stories across deserts, mountains, and dynasties. Conquest and cosmopolitanism ran parallel like two streams, all the while making way for dynamic standards of legitimacy, which could hinge as much on Persianate cultural fluency as on military might.

This article seeks to explore the intertwined trajectories of Hindustan and Central Asia during the long twelfth century, a period often studied in isolation within national or regional historiographies. As scholars, we are frequently trained to treat regions like South Asia and Central Asia as distinct historical theatres, each with its own internal logic and temporal rhythms. Yet, such compartmentalization risks obscuring the dynamic interactions and mutual entanglements that unfolded along their shared frontiers—zones of conflict, migration, commerce, and cultural exchange. This article, thus, examines the parallel political developments and interactions between the powers in Hindustan and the polities of the Mawara’ al-Nahr and the Khorasan in twelfth century, offering insights into how these diverse regions responded to similar challenges, all the while developing distinct political and cultural traditions. In doing so, the article aims to offer a more integrated, border-conscious history—one attuned to the currents of change that flowed across mountains and deserts as readily as they did through the corridors of empire.

The Turkic Prowess: Different, But Alike.

The Turkic polities in both Hindustan and Central Asia were essentially born of the game of musical chairs played across the breadth of Eurasia. The winners emerged when the music of the older empires abruptly stopped. Graduating from their supporting roles as slave-soldiers, mercenaries, and frontier raiders in the theatres of Abbasid, Ghaznavid, and Seljuk power, these Turkic understudies now became the masters of their own will and prowess. “The Turks,” as Marshall Hodgson wryly observed, “demonstrated a remarkable talent for inheriting the ruins of empires and constructing from these fragments something both derivative and startlingly original—like architectural salvagers with an avant-garde sensibility.”1

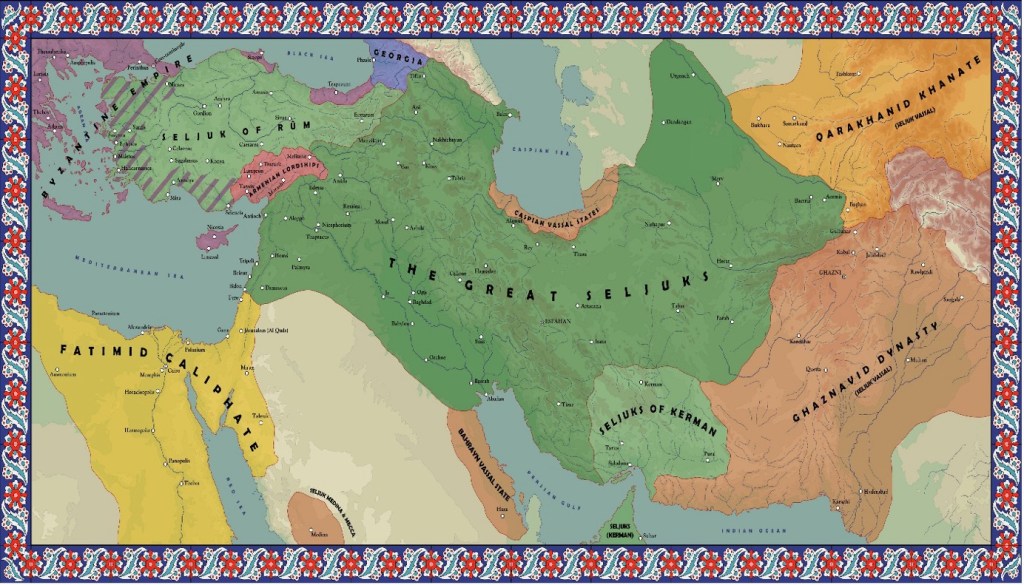

The period between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries bears testament to dramatic upheaval across the Islamic and Central Asian world. The Turks, bearing the status of mamluk (Arabic for ‘owned’) or ghulām (meaning ‘youth’ or ‘slave’), had been hired as military personnel by the Abbasids, more promptly so after Caliph al-Muʿtaṣim (r. 833–842) formalised their recruitment2, particularly from the Central Asian steppe regions (Mawara’ al-Nahr, Ferghana, and beyond). By the 11th century, entire dynasties—like the Ghaznavids—had been established by the fittest of these Turkic ghulām-commanders. On the other hand, were the Seljuks who, born as free Oghuz Turks and backed by caliphal investiture from the Abbasids, claimed the mantle of Islamic legitimacy and expanded into Persia, Iraq, and the Levant. However, towards the end of twelfth century, the weakening of the Abbasid Caliphate (750-1258), followed by the fall of the Ghaznavids (r. 977-1186) and Seljuks (r. 1037-1194), left a vacuum of power across vast territories stretching from the Iranian plateau to the Indian subcontinent. And once more, the music played—this time inviting new contenders to claim the thrones left momentarily bare. Two among them would define the political horizon on either side of the Hindu Kush: the Khwarazmians and the Ghurids.

Khwarazmians, initially the military governors (khwārazmshāhs) of the oasis region of Khwarazm (modern-day Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan), had essentially been subordinate to the Seljuk seat. Ethnically of Turkic origin, Khwarazmshahs were Persianised Turks who consolidated local power under the formidable leadership of the father-son duo, i.e., Ala al-Din Tekish and Muhammad II. They stretched their empire from the Aral Sea to as far as the Zagros mountains, beyond which lay the Abbasid seat in Baghdad. A defining moment came in 1194, when at the Battle of Ray (a southern suburb of modern-day Tehran), Tekish defeated the last meaningful Seljuk Sultan, Toghril III. At this stroke, the Seljuk order in Persia crumbled, and the Khwarazms took the imperial chair. Ghurids, who had accepted Seljuk authority and had risen as effective rulers of the Ghur hill region between Herat and Kabul, came directly for the Ghaznavid throat. Ala-ud-Din Husayn brought his Ghurid steel to the Ghaznavid soil at Tiginabad (Qandahar) in 1151 and let his superior infantry and strategy do the job. With Yamin-ud-Daula Bahram Shah—the Ghaznavid ruler, fleeing to Panjab, Ala-ud-Din entered Ghazni and levelled it with ruthless finality, earning for himself the laqab (an epithet) of Jahan-Suz(Burner of the World).

“The Ruler of Ghur [Ala al-Din Husayn] was a man of fierce countenance and fiercer temper. Having suffered imprisonment at the hands of Bahram Shah, he swore that should God grant him victory, he would leave no stone upon stone in the city of Ghazni. When his armies prevailed, he fulfilled his oath with such thoroughness that for generations men would say: ‘The wrath of the Jahan-Soz fell upon them.’”3

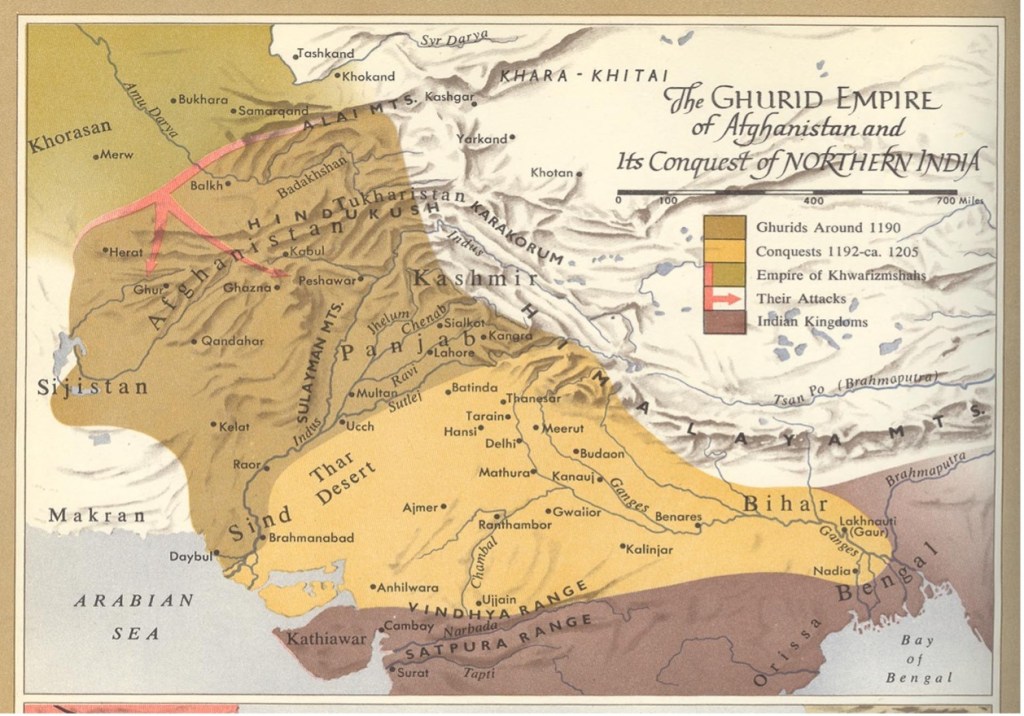

Though Ghazni was retaken by Bahram Shah, the shaken up Ghaznavid power never again found a solid ground beneath its feet. Until his death in 1161, the Jahaz-Suz turned to consolidating power within Ghur and extending Ghurid authority into Khorasan. In 1163, when his nephews, Ghiyas-ud-Din Muhammad and Mu’izzud-Din Muhammad, came to power, the Ghurid empire was still regional and relatively fragmented, but brimming with possibility. They had to their credit the key strongholds including Fīrūzkūh (their capital), Jām, Lāsh and Juwain, Bust, and parts of Herat; partial control over Khorasan’s eastern fringes, often contested with Seljuks and local dynasts, and a loose suzerainty or rivalry with regions such as Sistan, Garchistan and parts of western Punjab (where the last of Ghaznavids still held sway). Though closer to home, the Ghaznavids still lingered in the plains of eastern Afghanistan and the Punjab, ruled by Khusrau Malik; to their west, the Seljuks, once the towering overlords of the Islamic world, were in unmistakable decline as they awaited a final blow to their existence at the hands of the Khwarazmians (the Battle of Ray, 1194).

Stepping into this precarious arena and a volatile age, the Ghurid brothers inherited not an empire, but an opportunity. An opportunity to fill the vacuum left by fading powers and stalled ambitions; an opportunity that they did justice to by redrawing the political map—from Nishapur to Delhi, and from the Hindu Kush to the Ganges. From their highland capital at Fīrūzkūh and often clashing with the waning Seljuks and the rising Khwarazmians, Ghiyas-ud-Din consolidated power across Khorasan, extending Ghurid influence westward into Herat, Balkh, and the contested cities of Tus and Nishapur. Meanwhile, Mu’izzud-Din turned east towards the Indian Subcontinent. Piercing through the gates of Multan and subduing the Ismaili stronghold of Uchh, his defining moment came in 1186, when he extinguished Khusrau Malik, the last burning Ghaznavid lamp, in Lahore. With Lahore conquered and the Ghaznavid power wiped off the political map, the north of Hindustan lay open to him, only if there weren’t the Rajputs to give him a challenge. The Rajputs headed by Prithviraj Chauhan met the Ghurid forces at Tarain (modern day Haryana, 110 kilometres north of Delhi) in 1191, and repulsed the Ghurids back enough for Mu’izzud-Din to review his strategy and wait another year to launch a solid attack. in 1192, when the Ghurids reappeared they tilted the balance of power in Hindustan forever.

“Muhammad ibn Sam [Mu’izzud-Din Muhammad Ghuri] had studied well the reasons for his earlier defeat at the hands of the Rai [Prithviraj Chauhan]. This time, he arranged his forces in the ancient manner prescribed by the masters of war. At dawn, his horsemen charged with such discipline and fury that the Hindus, despite their multitudes, could not withstand the onslaught. When the dust of battle cleared, the sovereignty of Hind had passed from the hands of the Chauhans into those of Islam. Thus, did God grant victory to the faithful and render the unbelievers’ strength as dust scattered by the wind.”4

Thus, as the 13th century dawned over the eastern Islamic world, two towering powers met at the juncture of the Silken route: the Ghurids of Hindustan and the Khwarazmshahs of Transoxiana. While the Ghurids expanded eastward into the plains of northern India, building a network of client rulers and military slaves who would later birth the Delhi Sultanate, the Khwarazmshahs projected their might westward—into the fragmented heartlands of Persia, brushing dangerously close to the Abbasid Caliphate. Under Ala ud-Din Muhammad II, the Khwarazmian empire swelled to incorporate the entire expanse from the Oxus to the Zagros, presenting itself as a worthy inheritor, or rather, a challenger, to caliphal legitimacy. Yet beneath the sheer might of these nascent empires lay the tremors of fragility. Their frontiers—wide, loyalties—transactional, and their political cultures, though vibrant, carried within them the contradictions of conquest. The early 1200s were their apogee and their final flourish before the Mongol tempest would, once again, shatter the balance of power along the silken road.

“When the letter of the Sultan Muhammad Khwarazmshah reached the Caliph al-Nasir, demanding that he recognize him as Sultan over all lands of Islam and threatening to march on Baghdad with an army that would darken the sun, the Commander of the Faithful turned pale with anger. The missive proclaimed: ‘The age of the Arabs is over, and sovereignty now belongs to the Turks. Either the Caliph shall acknowledge me as supreme ruler of the East and West, or I shall establish another to sit upon the throne of Baghdad.’ It was then that al-Nasir, seeing the peril descending upon the house of Abbas, dispatched envoys to Genghis Khan, ruler of the Tatars.”5

By the 1210s, an unfamiliar name had begun to ripple across the caravanserais and courtly councils of Central Asia — Chengiz Khan, the lord of the eastern steppes. Chengiz Khan and his fellow Mongols were no mere raiders. Long before a full-scale invasion, Chengiz’s envoys and spies probed the porous borders of Transoxiana, measuring its wealth, routes, and resistance. When in 1215, he seized Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing) from the Jin, the Khwarazmian sultan Ala ud-Dīn Muhammad II dismissed them as an eastern distraction. Trade routes brought tales of entire cities levelled in China, of nomads who fought without fear, and of a khan who claimed the right to universal submission. The Mongols, for now, were still a horizon away — but the Silk Roads had begun to tremble.

The unravelling of the Khwarazmian Empire began not on a battlefield, but in the dust-choked streets of Otrar (present-day Kazakhstan, near the confluence of the Arys and Syr Darya rivers) in 1218, where a diplomatic blunder lit the fuse of destruction. That year, Chengiz had dispatched a caravan of Muslim merchants to open formal contact and commerce with Khwarazmshah Ala ud-Dīn Muhammad II. However, suspicion trumped diplomacy with the Khwarazmian governor Inalchuq having accused them of spying, seized their goods, and had them executed. When Chengiz sent three envoys demanding redress, the Shah deepened the insult—executing one, shaving and mutilating the rest. It was a grave violation of diplomatic sanctity, and the Mongol response was biblical in scale and strength. What followed was one of the most devastating campaigns in world history: in less than three years, the Mongols razed Bukhara, Samarkand, and Merv, annihilated entire cities, and drove the Khwarazmshah to die a fugitive in the Caspian wilderness. In that moment of arrogance and miscalculation, the Islamic East opened its gates to the wrath of the steppe.

In the Hindustan mainland, Mu’izzud-Din, after winning the Tarain battle, pressed deeper into the Indo-Gangetic plains. Between 1193 and 1205, his forces captured Delhi, Ajmer, Kannauj, and Benares, eroding the political authority of the Chauhans, Gahadavalas, and other Rajput confederacies. And yet, instead of administering these territories directly, Muhammad Ghūrī revived a time-honoured regimen within the Islamic world, entrusting governance to a cohort of loyal Turkic slave-commanders, the mamluks or ghulāms. In Qutb ud-Dīn Aibak, who administered Delhi, and Ikhtiyār ud-Dīn Bakhtiyār Khaljī, who conquered Bihar and Bengal, Ghūrī found loyal mamluks whose authority rested not in lineage, but in martial merit and personal allegiance. Thus, in the spring of 1206, as Muhammad Ghūrī returned westwards towards home after a punitive campaign in Lahore, he was slain by a Khokhar tribesman at Dhamiak, near the banks of Jhelum. At this moment, the empire that he left behind stretched precariously between restive Ghurid princes in the west, facing Khwarazmian encroachment, and a patchwork of mamluk-led provinces in Hindustan.

As the twelfth century drew to a close, the political landscape of both Central Asia and Hindustan stood on the cusp of transformation. In Hindustan, Ghūrī’s former slave and lieutenant, Qutb al-Dīn Aibak, seized Delhi in 1206 and laid the foundations of what would become the Delhi Sultanate. By 1219, the Mongol Empire, under Chengiz Khan, would descend upon Transoxiana with devastating speed, altering the fate of Khorasan and much of the Islamic East. Thus, as the thirteenth century opened, Hindustan embraced a new sultanate, while Khorasan and Mawara’ al-Nahr braced—unwittingly—for an empire from the steppe that would redraw the world.

The Silk Road: Not All Who Travelled Brought War

“The merchants who travel between Khwarazm and Ghur carry not only silver and gold, silk and spices, but also the hidden treasures of knowledge and faith. From their saddlebags come manuscripts alongside merchandise, and in the caravanserais, one hears as many debates on theology as haggling over prices.”6

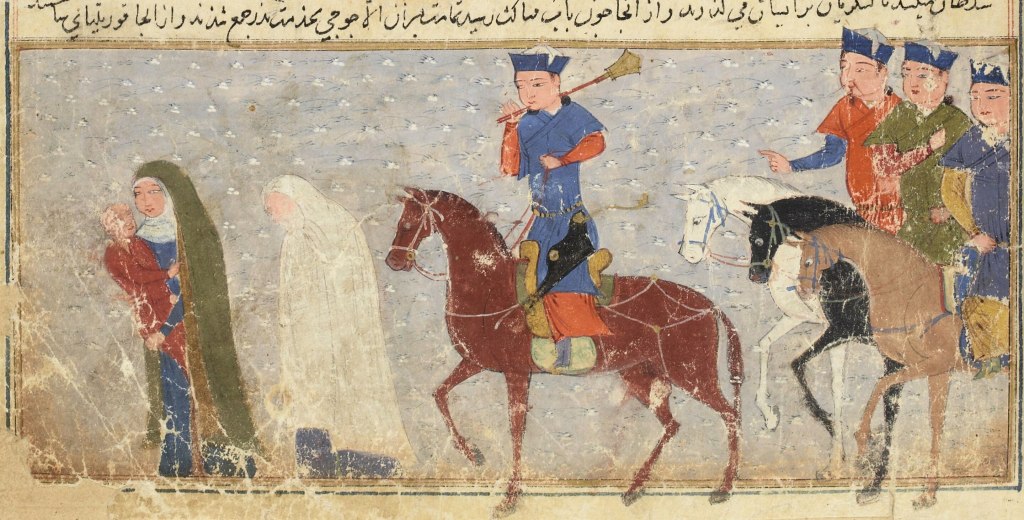

Beneath the tumult of conquest and rivalries, a subtle interplay of ideas and goods pulled the Khwarazmian and Ghurid realms towards one another. The commercial relationship between these empires was founded upon complementary economies. While the Khwarazmians controlled the rich agricultural basins of the Amu Darya (Oxus) river and dominated the northern routes connecting to the steppe, the Ghurids commanded the mountain passes leading to India’s wealth. Despite political tensions, this geographical arrangement made their cooperation almost inevitable. Ghurid territories supplied Indian cotton, indigo dyes, gems, and elephants northward, while Khwarazmian merchants sent Turkestan horses, Central Asian armor, Chinese silks, and Russian furs southward.

Critical of them all, was the horse trade. As Fakhr-i Mudabbir noted, “the armies of Hindustan would be nothing without the horses of Turkestan and Khurasan, which alone possess the speed and stamina needed for the lightning raids that bring victory.” Thus, the Khwarazm empire was an important supplier of these warhorses, creating a strategic reciprocity. With this reciprocity, grew the cosmopolitan hubs such as Delhi and Lahore in Hindustan, and Samarkand and Bukhara under the Khwarazms. These cities became vibrant centers where merchants, scholars, and artisans from diverse backgrounds mingled. While the political masters clashed on battlefields, the great libraries of Merv, Nishapur, Ghazni, and the khanqahs in Lahore and Delhi fed the intellectual and spiritual yearnings of scholars and saints. Ibn Jubayr, traveling through the region in the late twelfth century, noted with wonder, “Though the banners of Khwarazm and Ghur oppose each other in the field, their scholars sit side by side in the madrasas, their merchants drink from the same cups in the caravanserais, and their mystics chant the same divine names in their retreats. Such is the paradox of these lands where war and wisdom proceed hand in hand.”7

“The true miracle of the Silk Road,” observed the Kashmiri scholar Kalhana in his Rajatarangini, “is not that it delivers silk to those who desire it, but that it carries wisdom to those who never knew they thirsted for it.”8 Indeed, through these silken roads the commerce of ideas flourished alongside that of goods. Buddhist manuscripts travelled alongside chattering parrots from India; Sufi treatises accompanied perfumes from Persia; astronomical instruments journeyed with porcelain from China. The caravanserais that punctuated these routes became inadvertent academies where merchants exchanged not only silver but syllogisms, where pilgrims shared not only bread but benedictions. Even as Mongol armies shattered cities, they paradoxically created the conditions for unprecedented intellectual mobility through the Pax Mongolica that would follow the initial devastation. Through this period of political metamorphosis, the Silk Road performed its most profound service—preserving the continuity of human curiosity and cross-cultural admiration even as empires dissolved into dust.

Thus, as the thirteenth century dawned, the Silk Roads would once again become conduits for conquest, bearing Mongol cavalry across the heartlands of Khorasan and the fringes of Hindustan; yet even amid imperial collapse and geopolitical rupture, the enduring circuits of trade, pilgrimage, and intellectual exchange along these routes would persist and flourish—a testament to the Silk Roads’ deeper strength and logic, where the movement of ideas and aspirations ultimately proved more enduring than the ambitions of empires.

Jasleen Kaur

Jasleen Kaur holds a Master’s degree in History from Panjab University, Chandigarh, where she also completed her undergraduate studies with distinction. To further strengthen her pedagogical foundation, she pursued a Bachelor of Education from Punjabi University, Patiala. During this time, she developed a sustained interest in the Indo-Persian world, which led her to complete a Certificate Course in Elementary Persian, followed by an intensive language program offered by the Persian Research Center–New Delhi in collaboration with the Saadi Foundation, Iran, in which she scored 92% in the final examination. In 2020, Jasleen was offered a place in the MPhil in Late Antique and Byzantine Studies at the University of Oxford—a program she was unable to join due to financial constraints. Nevertheless, she has continued to pursue her research independently, with a particular focus on gender, sovereignty, and cultural transmission across the Persianate world. Her work broadly centres on a theme she has termed: “Veins of Influence: The Quiet Flow of Persian Thought and Taste in South Asia,” which explores the nuanced ways in which Persian literary and cultural traditions permeated and shaped Indian intellectual and artistic landscapes.

- “The Turks,” as Marshall Hodgson wryly observed, “demonstrated a remarkable talent for inheriting the ruins of empires and constructing from these fragments something both derivative and startlingly original—like architectural salvagers with an avant-garde sensibility.” ↩︎

- “Al-Muʿtaṣim came to favour the Turks because of their martial ability, and he relied increasingly on their service… He built Sāmarrāʾ so that they might be quartered away from the people of Baghdad.” al-Ṭabarī, The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume 33: Storm and Stress along the Northern Frontiers of the Abbasid Caliphate, trans. C. E. Bosworth (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1991), 110–113. ↩︎

- Fakhr-i Mudabbir, Adab al-Harb wa al-Shuja’at, trans. Iqtidar Husain Siddiqui (Lahore: Maktaba-i Jadid, 1965), 124-25. ↩︎

- Hasan Nizami, Taj al-Ma’athir, trans. Bhagwat Saroop, in Medieval India: A Miscellany, vol. 2 (Aligarh: Aligarh Muslim University, 1972), 86-87. ↩︎

- Ibn al-Athir, Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh [The Complete History], trans. D.S. Richards, The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi’l-Ta’rikh, Part 3: The Years 589-629/1193-1231: The Ayyubids after Saladin and the Mongol Menace (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), 205-206. ↩︎

- Abu’l-Hasan al-Marghinani, Kitāb al-Tijāra wa’l-Turuq [Book of Commerce and Routes], trans. S.M. Stern, in Trade and Commerce Between Central Asia and India During the 13th-14th Centuries (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1987), 143. ↩︎

- Ibn Jubayr, Riḥlat Ibn Jubayr [The Travels of Ibn Jubayr], trans. R.J.C. Broadhurst (London: Jonathan Cape, 1952), 213. ↩︎

- Kalhana, Rajatarangini [River of Kings], trans. Ranjit Sitaram Pandit (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1977), 211. ↩︎

Leave a comment