The introduction of tobacco into the Ottoman Empire at the end of the 16th century profoundly transformed social and cultural practices across Ottoman territories (Russell, 1756, p. 82). In a short time, smoking became a daily habit shared by all social classes, from humble artisans to the sultan himself. The rapid growth in consumption led to the emergence of a specific craft: the production of clay pipes, with Tophane in Istanbul becoming its most iconic center. This article first explores the modalities of tobacco diffusion and its integration into Ottoman society, before analyzing the role of Tophane as a major hub for the manufacture and distribution of tobacco-related material culture.

Tobacco, a plant native to the Americas, was introduced to the Islamic world via Europeans at the end of the 16th century. The first reliable references to its use in the Ottoman Empire date to around 1580–1600 (De Vincenz, 2016, p. 118). European travelers described scenes of men smoking long pipes in the streets of Istanbul, and Ottoman archives soon confirmed the rapid spread of the practice (Petchevi, 1866, p. 365). By the early 17th century, smoking had become a common activity in public spaces—coffeehouses, markets, caravanserais—as well as in domestic settings. Initially imported, particularly from Persia and Egypt, tobacco was gradually cultivated in the Balkans and Anatolia (Description de l’Égypte, Vol. III, Modern State, p. 417). A range of tobacco qualities emerged, from fine blends for the elite to coarser types consumed by the lower classes.

“Tobacco’s rise was not without controversy. Several sultans and religious scholars (ulema) opposed its use, sometimes perceiving it as a reprehensible innovation (bidʿa)”

Tobacco’s rise was not without controversy. Several sultans and religious scholars (ulema) opposed its use, sometimes perceiving it as a reprehensible innovation (bidʿa), especially since it encouraged visits to coffeehouses—spaces of social interaction and potential dissent (Lamartine, 1843, p. 66). In the 17th century, Sultan Murad IV formally banned tobacco consumption and ordered the execution of several violators (Süngü, 2014, p. 8). These prohibitions, however, proved largely ineffective and only fueled tobacco’s popularity. By the late 17th century, religious debates subsided: smoking had become an established practice. Some Muslim scholars even justified or recommended tobacco for its supposed medicinal benefits. Prohibition gave way to regulation: taxes were imposed, merchants had to register, and the Ottoman state began to profit from this new source of revenue.

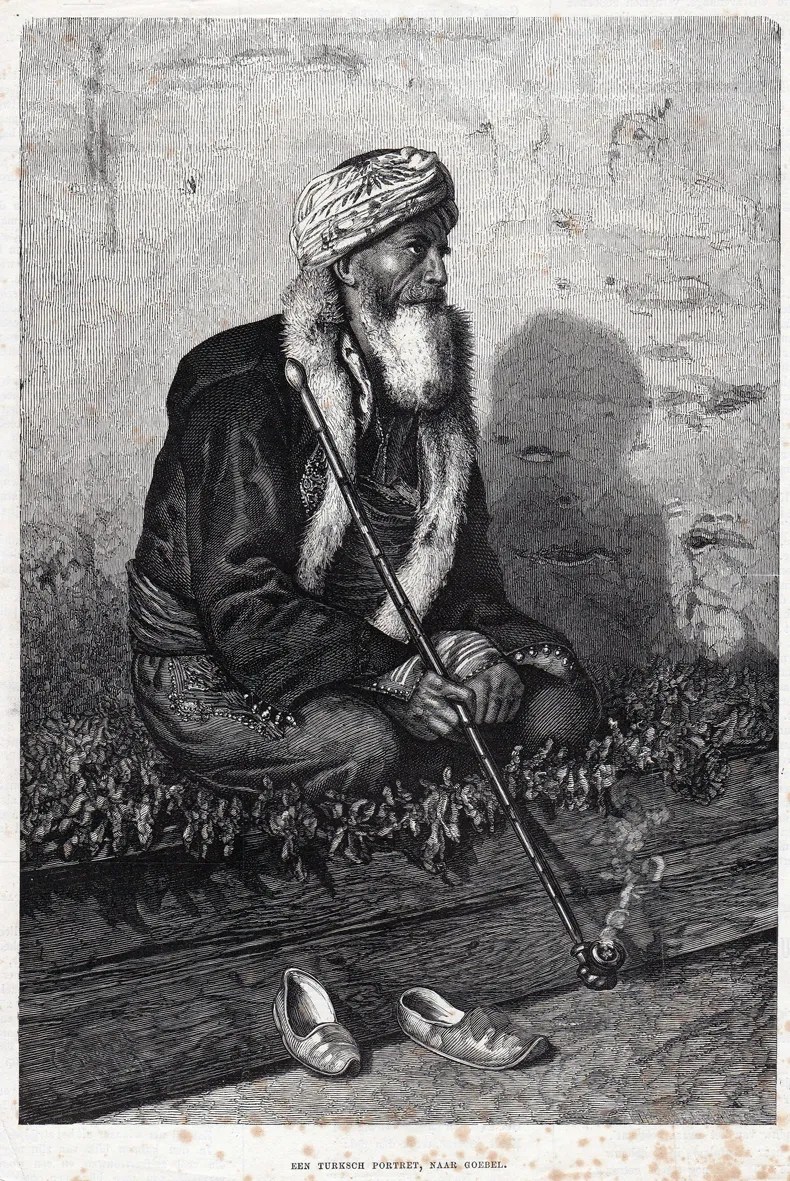

Smoking became a codified activity, a sign of civility, and a social act (Georgeon, 2010, p. 144). In Ottoman coffeehouses, customers lingered for hours with pipes in hand, discussing politics, listening to storytellers, or playing chess and backgammon. Offering a pipe was a gesture of hospitality. Pipes became personal and precious objects—often adorned, and sometimes passed down through generations. Women, though less visible in public, also smoked—particularly in domestic spaces or in public baths (hamams) (Bonnafont, 1883, p. 347). Smoking was also widespread among Janissaries, dervishes, and Sufi brotherhoods.

“By the late 17th century, religious debates subsided: smoking had become an established practice.”

The rise of tobacco consumption gave birth to a new everyday object: the pipe (lüle in Ottoman Turkish), composed of two main elements: the bowl (typically terracotta, but sometimes metal or stone) and the stem (wood, reed, or luxurious amber). Ottoman pipes came in a wide range of shapes, sizes, and decorations. Some were plain, others richly adorned with floral, geometric, or figurative motifs. Red ceramic pipes produced in Istanbul—particularly in Tophane—became especially renowned.

The Tophane district, located on the European shore of the Bosphorus between Karaköy and Fındıklı, takes its name from the former imperial cannon foundry (Tophane-i Amire). From the 17th century, the neighborhood became a center of artisanal and industrial activity, closely linked to the port of Istanbul, a nexus of maritime and land routes. Within this favorable context, a specialized production of clay pipes emerged to meet the growing demand in the capital and its provinces. Proximity to the port facilitated the import of raw materials (such as clay) and the export of finished products across the empire.

“Pipe production in Tophane was organized around family-run workshops, some of which achieved a high level of specialization by the 19th century. “

Pipe production in Tophane was organized around family-run workshops, some of which achieved a high level of specialization by the 19th century. These workshops were often concentrated on specific streets, such as Lüleciler Caddesi, literally “pipe-makers’ street,” which still bears witness to this artisanal heritage. Pipe-makers, known as lüleci, divided the labor: some specialized in preparing clay, others in molding, decorating, polishing, or firing (Description de l’Égypte, Vol. II, Modern State, p. 353). Most pipes were molded using wooden or stone matrices, allowing for semi-standardized production, though hand-modeled or engraved pieces also existed. The clay—likely sourced from Thrace or western Anatolia—was carefully prepared, sieved, and mixed with water to obtain a fine, homogeneous paste (Russell, 1756, p. 47). After shaping, the pipes were dried, polished, decorated, and fired in vertical-draft kilns reaching 900–1000°C.

Tophane pipes display distinctive technical and stylistic features. Typologically, they can be grouped into major categories based on the shape of the bowl. One common form is the ovoid or pear-shaped bowl, which was particularly prevalent during the 18th and 19th centuries. These pipes were often adorned with relief motifs such as palmettes, rosettes, wave patterns, and occasionally religious or honorific inscriptions. Another widespread type features a flared cylindrical form, generally simpler in design and more closely associated with mass production. Some pipes bear maker’s stamps, molded on the side of the bowl or under the base. These often include the artisan’s name, sometimes preceded by the phrase amal-i (“made by”), and are invaluable for studying production chronology and organization. Known stamps include names such as Mehmet, Ali Usta, Hasan, and Tophaneli İsmail (Bakla, 2007). Pipes were frequently finely polished, giving them a shiny appearance. They were then slip-coated for decorative effect or increased impermeability. Tophane pipes were renowned for their durability and aesthetic appeal, which explains their wide distribution throughout the Empire.

“Tophane pipes were renowned for their durability and aesthetic appeal, which explains their wide distribution throughout the Empire.”

From the 19th century onward, pipe production in Tophane reached a proto-industrial scale. Fiscal documents and 19th-century archives attest to hundreds of workshops in the district, producing millions of pipes annually (Bakla, 2007, p. 7). These were sold in Istanbul markets and exported to the Balkans, Central Anatolia, Egypt, Syria, and even Marseille (Gosse, 2007). Archaeological excavations in markets, baths, mosques, and private homes have uncovered thousands of Tophane pipe fragments, tracing their dissemination and local adaptation (Guedeau, 2022; Guedeau, 2025; François, 2022). However, some regions seem to have been less affected by Tophane production—such as northern Iraq, where local pipes predominated, or Arabia, where Levantine imports were more common.

“Fiscal documents and 19th-century archives attest to hundreds of workshops in the district, producing millions of pipes annually.”

Pipe-makers formed an organized guild (esnaf), with internal regulations governing pricing, quality, and access to the trade. The guild leader (şeyh) oversaw the transmission of skills, workshop organization, and relations with imperial authorities. Some master pipe-makers (usta) enjoyed great prestige and employed dozens of apprentices (çırak). Pipe-making was officially recognized, and high-quality pipes were sometimes included in diplomatic gifts or prized as prestige objects.

The early 20th century marked the gradual decline of the traditional pipe. While tobacco remained ubiquitous in Ottoman society, consumption patterns evolved. The pipe was increasingly replaced by the cigarette, more convenient in a time of accelerated lifestyles and imperial modernity. The last pipe workshop closed in 1928 (Bakla, 2007, p. 302). Tophane gradually lost its artisanal function, shifting toward other industries (mechanical, maritime commerce, military installations). Pipe artisans either changed trades or left the area. Today, no pipe workshops remain active in Tophane. Nevertheless, the memory of this production center lives on through museum collections (such as the Sadberk Hanım Museum in Istanbul and the Archaeological Museum of Izmir), archaeological publications, and academic research on Ottoman material culture. Despite recent gentrification, the architectural heritage of the district still bears traces of its artisanal past—in street names and historic buildings.

“The pipe was increasingly replaced by the cigarette, more convenient in a time of accelerated lifestyles and imperial modernity.”

Archaeological excavations in Istanbul and in provincial areas—especially the Levant and Mesopotamia—have revealed a wealth of pipe fragments. These finds have enabled the reconstruction of regional and chronological typologies. Long overlooked, such objects are now recognized as valuable indicators of daily life, trade networks, and popular consumption.

Tobacco consumption was one of the most significant cultural revolutions of the early modern Ottoman world. It reshaped social habits, fostered new forms of sociability, stimulated a flourishing craft industry, and transformed material culture. The Tophane pipes are among the most eloquent symbols of this change: everyday objects, yet refined artisanal creations, they accompanied generations of Ottomans in both domestic and public life. Studying these artifacts allows us not only to understand the diffusion of a novel substance within a Muslim empire, but also to explore the economic, social, and artistic dynamics of a world in transformation.

Nolwenn Guedeau

Nolwenn Guedeau is a research associate at the Bonn Center for Dependency and Slavery Study, doing a PhD at Bonn University and Aix-Marseille University. Her research focuses on ottoman archaeology, material culture and identity. She has been working mostly in Iraq and Saudi Arabia, exploring the multicultural borders of the empire

Bibliography:

- Bakla, Erdinç. Tophane lüleciliği: Osmanlı’nın tasarımındaki yaratıcılığı ve yaşam keyfi. Antik A.S. Yayınları, 2007.

- Bonnafont, Jean-Pierre. Douze ans en Algérie: 1830 à 1842. Paris: E. Dentu, Librairie-Editeur, 1883.

- La Description de l’Égypte, ou Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française. État Moderne. Vol. 2. Paris, 1809.

- La Description de l’Égypte, ou Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l’expédition de l’Armée française. État Moderne. Vol. 3. Paris, 1809.

- Lamartine, Alphonse De. Voyage en Orient. Librairie De Charles Gosselin. Vol. I, 1843.

- Georgeon, François. « Le génie de l’ottomanisme. Essai sur la peinture orientaliste d’Osman Hamdi (1842-1910) ». Turcica 42 (2010): 143-66.

- Guedeau, Nolwenn. « Ottoman smoking pipes in Bilad ash-Cham ». Carnet de l’IFPO, Hypothese.org, 2022.

- Guedeau, Nolwenn. « Smoking at the Border of the Ottoman Empire ». In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, par Scott D. Haddow, Camilla Mazzucato, et Ingolf Thuesen, 479‑504, Harrassowitz Verlag. Wiesbaden, 2025.

- Petchevi I., Peçcevi Tarihi, Constatinople, I, 1866

- Russell, Alexander. The Natural History of Aleppo and Parts Adjacent. Containing a Description of the City, and the Prcinipal Natural Productions in Its Neighbourhood ; Together with an Account of the Climate, Inhabitants, and Diseases ; Particularly of the Plague, with the Methods Used by the Europeans for Their Preservation. London: A. Millar, 1756.

- Süngü, Ertuğrul. « Understanding different interactions of Coffee, Tobacco and Opium culture in the Lands of Ottoman Empire in the light of the pipes obtained in Excavation ». Master Thesis, Istanbul Bilgi University, 2014.

- De Vincenz, Anna. « Chibouk smoking pipes – secret and riddles of the ottoman past ». In Arise, walk throught the land. Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Land of Israel in memory of Yizhar Hirschfeld on the Tenth Anniversary of his Demise, par Josephe Patrich, Orit Peleg-Barkat, et Erez Ben-Yosef, 111‑20, The Israel Exploitation Society. Jerusalem, 2016.

Leave a comment