The meaning of the contemporary word ‘barbarian’ still bears little resemblance to the original Greek word βάρβαρος – which initially carried the rather neutral meaning of ‘non-Greek’. The oldest attestation of the notion can be found in the Iliad (II, 867), appearing in the compound βαρβαρόφωνος, which could mean both ‘speaking an unintelligible language’ and ‘speaking Greek badly’ (Sucharski 2012: 125-126). Interestingly, Homer uses this adjective as an epithet associated with the Carians. Since this Anatolian people had good relations with the Greeks, its meaning probably corresponds to the latter meaning (Hall 2002: 112).

“The sharp dichotomy between ‘Greek’ and ‘non-Greek’, virtually absent in the Archaic period, only emerges from the fifth century BCE.”

The sharp dichotomy between ‘Greek’ and ‘non-Greek’, virtually absent in the Archaic period, only emerges from the fifth century BCE. In Classical Greece, βάρβαρος takes on a very pejorative denotation: non-Greeks were scorned; Greeks started looking at foreigners in a stereotypical and even derogatory way (Hall 2002: 103). Although the Greeks were not fascinated by languages other than their own ‘superior’ Greek, they did show interest in other cultures, and sometimes even admired them. Nevertheless, they regarded themselves as the supreme people, adopting barbarian cultural elements and exceeding them, as Plato states (the authorship, however, is disputed):

“Let’s take for granted that whenever Greeks borrow from barbarians, they eventually bring it to perfection.” (λάβωμεν δὲ ὡς ὅτιπερ ἂν Ἕλληνες βαρβάρων παραλάβωσι, κάλλιον τοῦτο εἰς τέλος ἀπεργάζονται) (Epinomis 987e)

“Later, in Hellenistic society, ‘being Greek’ became a central ideal to which barbarians could aspire through education and culture (παιδεία).”

Later, in Hellenistic society, ‘being Greek’ became a central ideal to which barbarians could aspire through education and culture (παιδεία). Therefore, the (Hellenistic) Greeks were not racist in the contemporary meaning of the word; through παιδεία, everyone – regardless of origin – was basically able to become Greek. Lucian of Samosata (in modern south-eastern Turkey) is one of the most striking examples of a barbarian becoming Greek. Born to a Syriac family and raised along the banks of the Euphrates, Lucian learned and studied Attic Greek. He reached such an astonishing level of linguistic mastery that his writings have become models par excellence of how to write perfect Greek. In addition, many non-Greeks used the Greek language to write books about their own history, traditions and culture for a Greek audience. For instance, Berossus set out the Babylonian history and culture in his Babyloniaca; Manetho did the same for Egypt in his Aegyptiaca. Even the earliest examples of Roman historiography were written in Greek (i.e. the works by Fabius Pictor, Cincius Alimentus and Acilius). On the other hand, the number of works where Greeks put ‘barbaric’ societies on the same level as their own Greek, appears to be extremely low. An example can be found in (Pseudo-)Longinus’ Περὶ ὕψους (“On the Sublime”), a work of literary criticism on aesthetics, where the author pays (little) attention to Jewish culture by referring positively to the Book of Genesis, part of the Septuagint (the earliest Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament) (Sucharski 2012: 126-128).

Dr. Keersmaekers en Professor Van Hal (2021: 213-225), researchers at the University of Leuven, attempted to elucidate the semantic evolution of the term ‘βάρβαρος’ using a corpus linguistic approach. They sought to examine the use of the term throughout the classical and post-classical Greek period, through both semasiological as onomasiological perspectives. Whereas the first approach explores how βάρβαρος is used over time, in particular by checking which words the term is frequently combined with, the latter provides a conceptual overview of terms similar to βάρβαρος. Apparently, the more descriptive meaning ‘non-Greek’ seems to dominate the corpus, even in the later periods. Probably, the more subjective, pejorative use of the term gradually develops from the second century CE onwards (e.g. βάρβαρος μεγαλαυχία ‘barbarian arrogance’). Looking from the onomasiological perspective, βάρβαρος largely represents ‘foreignness’, while the subjective, negative notion of ‘primitivity’ hardly stands out.

Rik Verachtert

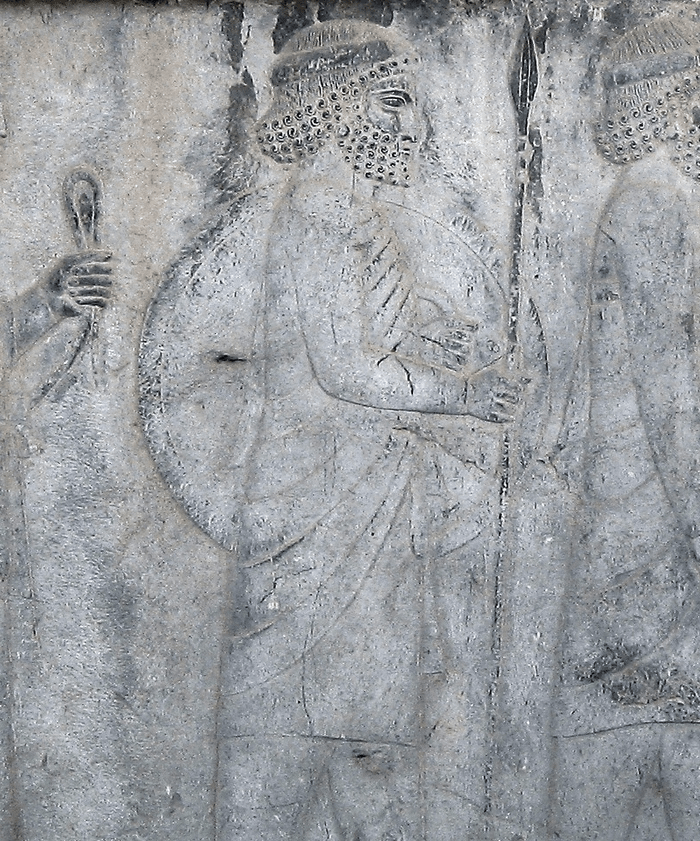

The Dying Gaul. Capitoline Museums, Rome

Sources:

- Hall, J. M., Hellenicity. Between Ethnicity and Culture, 2002, Chicago.

- Keersmaekers, A. & T. Van Hal, “A Corpus-Based Approach to Conceptual History of Ancient Greek: The Case of βάρβαρος”, Cognitive Sociolinguistics Revisited, eds. G. Kristiansen, K. Franco, S. De Pascale, L. Rosseel & W. Zhang, 2021, Berlin, pp. 213-225.

- Sucharski, R. A., “A Few Observations on the Distinctive Features of the Greek Culture”, Colloquia Humanistica(1), 2012, pp. 125-134.

Leave a comment