One of the central pillars of the civilisations that emerged along the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates since the early third millennium BCE was their mastery of the art of writing (Sumerian: namdubsar / Akkadian: tupšarrūtu). This, in fact, distinguished them from many other societies around the globe at that time. This major innovation is seen as the defining moment which kickstarted “history”, as opposed to the “darkness” of prehistoric illiteracy. Suddenly, thoughts, speech, and agreements could be recorded on a tablet, changing the whole dynamic of society. The concept of a “contract” irreversibly bound people to their promises—unless they destroyed the evidence. Laws could be put on stone, affirming and protecting the idea of unshakeable and eternal justice. Ingenious minds could now entrust their knowledge, ideas, and creativity to tablets for others to enjoy and learn. Friends, relatives, and business associates were now able to exchange, word for word, their wishes and emotions over vast distances through letters. Mythical stories and legends became canonized, with writing gradually presenting the idea of one “true” version.

At the heart of all of this was the scribe, known in Akkadian as the tupšarru, derived from the Sumerian word for writer, dubsar. However, despite the importance of writing in ancient Iraq, literacy was reserved for a relatively small group of people. In fact, committing one’s child to education instead of labour demanded a considerable amount of wealth. The child then had to memorize hundreds of signs of the complex syllabic cuneiform writing system before he could become a professional writer. This made the tupšarru all the more powerful.

The complexity of the scribal art necessitated the emergence of specialized institutions devoted entirely to the teaching of cuneiform to the next generation. This article aims to shed light on these schools, focusing on the Old Babylonian period (2000–1600 BCE), which is best represented in our archaeological and written source material. How did they function? What were they like?

The Scribal School

A scribal school was called an edubba (Sumerian: 𒂍𒁾𒁀𒀀), a compound of the Sumerian words for “house” (e) and “tablet” (dub). The Akkadian-speaking community literally translated the word into bīt ṭuppi (“house of the tablet”), explaining the occasionally used English translation “tablet-house.” These institutions date back to when the Sumerians dominated ancient Iraq, i.e. the third millennium BCE. Our earliest archaeological attestations of scribal schools, however, are from the Old Babylonian period (2000–1600 BCE), when the city of Babylon rose to prominence for the first time under the leadership of the famed king Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BCE).

According to Besso Landsberger (1890–1968), these Old Babylonian schools initially had something of an official, public status. After the Old Babylonian period, these institutions gradually disappeared. The education in writing came to be dominated by a few influential families that monopolized this knowledge until the disappearance of cuneiform writing during the Parthian period (2nd century BCE – 3rd century CE).1

“most seem to have been modest and private institutions already during the Old Babylonian period”

Archaeological research, however, has largely refuted this view. Although some school tablets were found within the precincts of the palace of Larsa during Nur-Adad’s reign (c. 1865–1850 BCE), suggesting that royal schools may have existed, most seem to have been modest and private institutions already during the Old Babylonian period.2 This has been substantiated by the uncovering and research conducted at House F in Nippur3, No. 7 Quiet Street and No. 1 Broad Street at Ur—run by the headmaster Igmil-Sîn4—and other sites such as Mari.5 These school buildings do not appear to differ from normal dwellings.6 This gave rise to the idea that many school activities might have been conducted outside in the courtyard. Indeed, brief allusions have been found to the courtyard as a place where oral examinations and interrogations were held.7 At Mari, two rooms have been uncovered that seem to have functioned as classrooms.8 Additionally, shallow water troughs have been found here, which supposedly stored the wet clay to be moulded into tablets by the teacher and his students.

At any rate, given the small scale of these schools, they probably didn’t accommodate many students simultaneously, likely giving priority to kinsmen and children of colleagues. It thus appears that the scribal art was already dominated by a few families from the outset, passed from one generation to the next like any other craft in ancient Mesopotamia.

The archaeologically attested small size of these schools has confronted researchers with one major issue: the schools described in the Edubba-literature appear significantly larger than those unearthed by archaeologists. A.R. George resolves this apparent discrepancy by arguing that these texts actually describe schools from the earlier Ur III period (22nd–21st centuries BCE), during which large-scale learning centres emerged in cities such as Nippur and Ur.9 These predecessors of the Old Babylonian scribal academies were built to educate the growing bureaucracy of this empire.10 These grand institutions were in all probability state-sponsored, with the king taking an active interest in them, as reflected in several hymns.11 These schools, in fact, also functioned as centers of royal propaganda, with their literary compositions—such as hymns—idealizing the monarch and his reign. One central figure in the history of these large schools seems to have been King Shulgi (r. c. 2094–2046 BCE). As these Ur III academies were significantly larger, it is logical to assume learning took place in purpose-built structures. After the fall of the Ur III dynasty, these royal academies slowly disappeared, making way for the smaller Old Babylonian scribal schools. The legacy of these large Sumerian institutions endured, however, with their corpus of literary texts serving as study material for scribes in the centuries to come.

What did they study?

Central to the Old Babylonian scribal schools was the transmission of Sumerian knowledge and language. Despite Semitic peoples gradually taking over the reins in Mesopotamia ever since the Akkadian Empire (c. 2334 – c. 2154 BCE), Sumerian culture endured and was held in high esteem in the land of the Tigris and Euphrates. Their ancient wisdom was deeply treasured and admired by the Babylonians, who became determined to keep their legacy alive—even after Sumerian ceased to be a spoken language sometime during the early second millennium BCE. It remained the principal sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Mesopotamia for centuries to come. An obvious parallel can be drawn with the status of Latin in medieval and Renaissance Europe. In any case, the scribal schools were the main centres for preserving Sumerian culture. Some sources suggest that Sumerian was the only language permitted at school, with students punished for uttering even a single word in Akkadian.12 When they graduated, students were proud to call themselves “Sumerian” and even adopted Sumerian versions of their names.13

“Sumerian knowledge acquired through these lists covered a vast array of topics: astronomy, mathematics, grammar, music, land-surveying, magical formulae, geography, and more”

Several interesting documents have emerged revealing their exact study materials, such as lexical lists of Sumerian words with their Akkadian translations, which the students were expected to learn by heart. The Sumerian knowledge acquired through these lists covered a vast array of topics: astronomy, mathematics, grammar, music, land-surveying, magical formulae, geography, and more. The use of lists as study material was not new—some of our earliest examples hail from Uruk and can be dated to around 3000 BCE. “Such ‘dictionaries’ are of enormous value to modern scholars. They reveal too the extraordinary breadth and curiosity, and indeed the limitations, of Sumerian scholarship,” as Joan Oates remarks.14

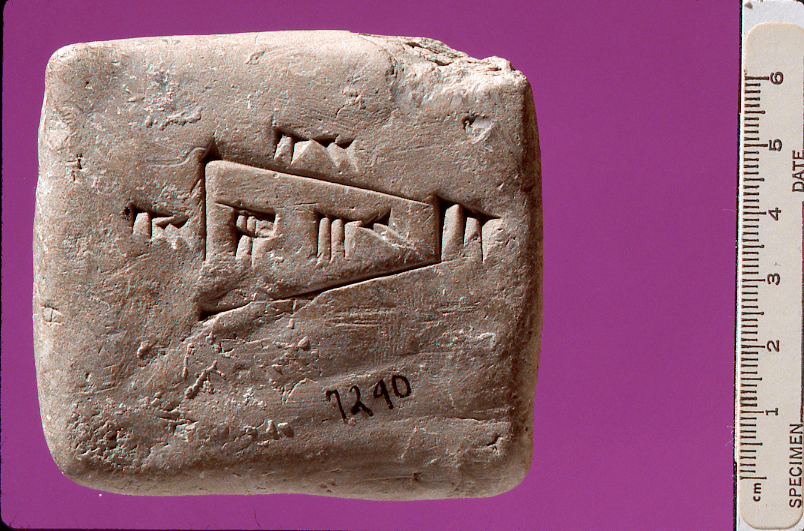

Numerous practice tablets (imsar šubba) have been unearthed, shedding light on the students’ learning process.15 Absolute beginners first practiced their writing with elementary syllabic exercises in the vowel sequence “u-a-i”, such as tu-ta-ti.16 They were then expected to memorize a vast sign list of over 900 entries, followed by the learning of the aforementioned lexical lists. More advanced pupils copied full sentences on the reverse of a tablet, which a senior member of the college (šešgal) had written on the obverse.17 It is sometimes easy to distinguish the hand of the master from that of the student. Occasionally, we see the pupil’s section on the practice tablet cut off, while the rest was preserved for later use.

“it becomes clear that before graduation, students were expected to fully master the composition of Akkadian bureaucratic documents.”

It is unclear how their own language, Akkadian—the language of the bureaucracy—fit into this framework. At what point did the students begin to learn the cuneiform variant for Akkadian and the formulae required to set up legal and administrative documents? Christopher Lucas has suggested that from the outset, classes were conducted in the vernacular, with increasing amounts of Sumerian spoken and written as the student advanced. From the “Examination Text A” (cf. infra), it becomes clear that before graduation, students were expected to fully master the composition of Akkadian bureaucratic documents. They therefore studied numerous anthologies of law in both Sumerian and Akkadian, such as the Codex of Lipit-Ishtar (c. 1920 BCE), the Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100 BCE), and the legendary Code of Hammurabi (c. 1750 BCE), paying special attention to their legal phraseology. Thus, graduates were set on a course toward lucrative legal and administrative positions at the royal court or the mighty temples. Some scribes became incredibly influential, with several attested as close advisors to kings in matters of state. Scribes particularly gifted in legal matters could also pursue a career as recorders in courts of law (Sumerian: dumu edubba / Akkadian: ša dajjāni). Besides filling the ranks of the bureaucracy, many scribes worked as freelancers, offering their services to anyone needing to draft a contract or file a lawsuit. We know many of these writers by name, as every document reserved a section to record who wrote it.

“Sumerian remained the central and most prestigious subject at school”

Nevertheless, Sumerian remained the central and most prestigious subject at school. Scribes who did not know this revered language were looked down upon by their colleagues, as becomes clear from the proverb: “What kind of a scribe is a scribe who does not know Sumerian?”18 Sumerian literature, therefore, occupied a central place in the curriculum. Especially during his later years at the edubba, the student was expected to study and memorise large portions of Sumerian literature, as attested by numerous practice tablets. It was, in fact, through the remnants of these tablets that scholars have been able to reconstruct the canonical corpus of Sumerian literature.19 These sources reveal the richness of Sumerian literary heritage, with a wide range of genres: hymns, epics, laments, love songs, lullabies, prayers, elegies, records of royal correspondence, and legal compendia. Besides these written texts, there was also a corpus of orally transmitted literature (ša pi ummāni) which students were expected to memorise and recite. It is important to note, however, that during the Old Babylonian period, Akkadian was increasingly utilized as a literary language in its own right, gradually liberating itself from its Sumerian models.20

“The scribal art is not easily learned … Strive to master the scribal art and it will enrich you.”21

The bilingual “Examination Text A” (1720–1625 BCE) sheds light on how students may have been examined. The young pupil (dubsar tur) sits with his school-father (ummia) in front of a board of masters in the courtyard. He is then questioned by his ummia: “Do you know the scribal art that you have learned?”, to which the student confidently replies in the affirmative. What follows is a relentless barrage of difficult questions. He is asked to translate back and forth between Akkadian and Sumerian. He must show his knowledge of different types of calligraphy and occult script. He is expected to understand the intricacies of Mesopotamian society and is questioned about the various classes of priests and professions. He must prepare an official document and seal. He is confronted with mathematical problems relating to the allocation of rations and the division of fields. In short, the scribal student was expected to become an all-round educated man, well equipped to function within the bureaucracy of the temple or palace.

Life at School

“Come, my son, sit at my feet. I will talk to you, and you will give me information! From your childhood to your adult age you have been staying in the tablet-house. Do you know the scribal art that you have learned?”22

The students must have hailed from well-to-do households. Committing a child to an education that lasted from a very young age into adulthood was a significant commitment in a society where children sometimes had to start working as early as age five to help make ends meet. Students in the Old Babylonian schools were exclusively male, although evidence suggests that a considerable number of women could read and write during this period. Some separate arrangement must therefore have existed for the education of women.

“If the young son of the edubba

Has not recited his tasks correctly,

The elder brother and his father will beat him.”23

“If you study night and day and work all the time modestly and without arrogance,

If you listen to your colleagues and teachers,

You still can become a scribe!”24

Life at school was certainly no walk in the park. Hours were long—from sunrise to sunset—expectations were high, and punishments were harsh, usually involving a whip. Several cuneiform sources, such as Schooldays and Edubba D, describe life at school.25 Although literary creations laced with satire, they nonetheless offer valuable insights into the learning environment. Members of the institution collectively referred to themselves as dumu edubba, “school-sons.” They simultaneously referred to each other as family members. The teacher, also known as the master (ummia), was the “father” (adda edubba), while his students were his “sons.” Senior students were called the “older brothers” (šešgal) and appear to have overseen much of the education of their younger peers.

These older students were responsible for preparing the practice tablets for the younger ones (dubsar tur), as discussed earlier, and for administering their oral examinations. Other school figures are also referenced in the sources, such as the ugula, who may have been a kind of clerk responsible for administrative tasks and enforcing school rules. A specialized teacher in mathematics (dubsar ni šid) appears as well, alongside other functionaries. These roles are known primarily from the edubba literature, which—as discussed above—likely reflects the larger academies of the Ur III era rather than those of the Old Babylonian period. It remains unclear to what extent this hierarchical structure persisted into later times.

That said, the use of familial terms such as “father,” “brother,” and “son” may not have been purely symbolic in the Old Babylonian period. Given the private nature of these later schools, the teacher may quite literally have been the students’ father.

It is uncertain how the edubba (bīt ṭuppi) evolved in the centuries following the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire. No archaeological evidence confirms their survival, but there is likewise no definitive proof of their disappearance. It is likely that they remained small, private institutions reserved for the fortunate few. We are extremely indebted to these institutions for our knowledge of education in Ancient Mesopotamia, as well as for our knowledge of Sumerian.

Olivier Goossens

Bibliography

- Charpin, D., Le clergé d’Ur au siècle d’Hammurabi, 1986, Geneva-Paris.

- Civil, M., “Sur les ‘livres d’écolier’ à l’époque paléo-babylonienne”, Miscellanea Babylonica: Mélanges offerts à Maurice Birot, eds. J.-M. Durand & J.-R. Kupper, 1985, Parijs, pp. 67-78.

- Edzard, D., Heidelberger Studien zum alten Orient, 1967, Wiesbaden.

- Gadd, C., Teachers and Students in the Oldest Schools, 1956, London.

- Gordon, J., Sumerian Proverbs, Glimpses of Everyday Life In Ancient Mesopotamia, 1968, New York.

- Hallo, W., “Toward a History of Sumerian Literature”, Sumerological Studies In Honor Of Thorkild Jacobsen, 1976, Chicago, pp. 181-203.

- Kramer, S., Schooldays: A Sumerian Composition Relating to the Education of a Scribe, 1949, Philadelphia.

- Lambert, W., “Ancestors, authors and canonicity”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Vol. 11, 1957, pp. 1-14.

- Landsberger, B., “Scribal concepts of education”, City Invincible, eds. C. Kraeling & R. Adams, 1958, Chicago, pp. 94-101.

- Landsberger, B., “Zum ‘Silbenalphabet B’”, Zwei altbabylonische Schulbücher aus Nippur, 1959, Ankara, pp. 97-116.

- Lucas, C., “The Scribal Tablet-House in Ancient Mesopotamia”, History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 19, 1979, pp. 305-322.

- Nissen, H., “The education and profession of the scribe”, Archaic Bookkeeping. Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East, eds. H. Nissen, P. Damerow & R. Englund, 1993, Chicago, pp. 105-109.

- Oates, J., Babylon, 1986, London.

- Sjöberg, Å., “The Old Babylonian Eduba”, Sumerological Studies in Honor of Thorkild Jacobsen, 1976, Chicago, pp. 159-179.

- Sjöberg, Å., “An Old Babylonian schooltext from Nippur”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, Vol. 83, 1993, pp. 1-21.

- Stone, E., Nippur Neighbourhoods,1987, Chicago.

- Tanret, M., “Les tablettes ‘scolaires’ découvertes à Tell el-Dēr”, Akkadica, Vol. 27, 1982, p. 39.

- Tinney, S., “Texts, tablets, and teaching: scribal education in Nippur and Ur”, Expedition, Vol. 40, 1998, pp. 40-50.

- Tinney, S., “On the curricular setting of Sumerian literature”, Iraq, Vol. 61, 1999, pp. 159-172.

- Volk, K., “Edubba’a und Edubba’a Literatur: Rätsel und Lösungen”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, Vol. 90, 2000, pp. 1-30.

- Von Soden, W., Zweisprachigkeit in der geistigen Kultur Babyloniens, 1960, Wenen.

- Waetzoldt, H., “Keilschrift und Schulen in Mesopotamien und Ebla”, Erziehungs- und Unterrichtsmethoden im historischen Wandel, eds. L. Kriss-Rettenbeck & M. Liedtke, 1986, Bad Heilbrunn.

- Sjöberg 1976, 159-160; Landsberger 1958, 97. ↩︎

- Lucas 1979, 311. ↩︎

- Stone 1987, 56-59. ↩︎

- Charpin 1986, 419-86. ↩︎

- Parrot 1958, 186-191. ↩︎

- Volk 2000, 7-8; Tanret 1982, 49. ↩︎

- Lucas 1979, 310. ↩︎

- Parrot 1958, 186-191. ↩︎

- George 2001, 5. ↩︎

- Waetzoldt 1986, 39. ↩︎

- Castellino 1903, 60-3; Nissen 1993, 108. ↩︎

- Schooldays 38-41. ↩︎

- Lambert 1957, 6-7. ↩︎

- Oates 1986, 164. ↩︎

- Tinney 1998, 1999. ↩︎

- Landsberger 1959, 98. ↩︎

- Lucas 1979, 311. ↩︎

- Gordon 1968, 206. ↩︎

- Hallo 1976, 181-203. ↩︎

- Von Soden 1960; Edzard 1967, 185-199. ↩︎

- Examination Text A ↩︎

- Landsberger B1960 ↩︎

- Gadd 1956, 20. ↩︎

- Landsberger B1960. ↩︎

- Kramer 1949; Civil 1985. ↩︎

Leave a comment