From the 16th to the 19th centuries, the art of carpet weaving in the Islamic world underwent a transformation so profound that it reshaped not only textile traditions but also the very identity of courtly material culture. What once was a modest craft when patterns passed quietly from generation to generation within villages and nomadic tribes – eventually evolved into a state-sponsored industry. In the imperial courts of the Ottomans, carpets became the canvas for sophisticated design, technical refinement, and symbolic prestige.

The Ottoman sultans oversaw the creation of weaving ateliers where master designers worked alongside the most skilled artisans. Patterns were no longer exclusively rooted in inherited tribal designs but were instead envisioned within royal workshops, drawing inspiration from architecture, manuscript illumination, and global luxury textiles. The result was a golden age of carpet production, in which these woven masterpieces traveled far beyond the courts that commissioned them – finding homes in the palaces of Europe and the trading houses of the Far East.

In Europe, such carpets were considered too precious for the normal footfall. They were draped over banquet tables, placed upon furniture, or hung as wall adornments, serving as visible emblems of wealth and refined taste. Within the Islamic world, they were equally treasured and acquired by royal households, displayed on ceremonial occasions, and preserved as part of dynastic collections.

Prelude to Ottoman Splendour

“traditions of carpet weaving predated the Ottoman ascendancy”

In Anatolia, the traditions of carpet weaving predated the Ottoman ascendancy. For centuries, Turkish, Armenian, Caucasian, and Kurdish communities had produced geometric and animal-patterned rugs when objects were shaped by nomadic necessity and tribal symbolism. Woven to cover tent floors or to serve as bedding, these carpets had to be portable, durable, and practical. Yet even within these limitations, they carried rich aesthetic language: stylized fauna, angular motifs, and bold color contrasts.

The Seljuk Turks, whose reign in Anatolia began after their victory at Manzikert in 1071 CE, were central to early Anatolian weaving history. While weaving certainly predated their arrival, the earliest surviving Seljuk carpets date from the 13th century and were discovered in Konya, Beyşehir, and Fostat. Measuring up to six meters in length, these monumental examples could not have been made in nomadic tents – signaling organized production in urban production centres. Seljuk patterns leaned heavily toward geometric precision: hexagons, squares, and rhomboids aligned in diagonal rows, ornamented with stars, flowers, or stylized leaves. Borders often bore Kufic-inspired ornamentation, evoking the angular elegance of early Arabic script. The color palette favored subdued blues, reds, and greens, dyed from natural sources. The structural hallmark was the symmetrical ‘Ghiordes’ knot, still recognized as the defining knot of Turkish weaving.

Surface Design Traditions in Ushak

By the late 13th century, the Seljuk hold weakened under Mongol pressure, paving the way for the rise of the Ottomans around 1300 CE. As Ottoman power expanded, so too did their textile networks. The empire’s conquests in Persia and Egypt during the early 16th century introduced new artistic vocabularies. Anatolian workshops absorbed Persian medallion compositions and the saz style: designs of flowing arabesques and fantastical foliage. These courtly motifs, first cultivated in Istanbul, radiated outward to weaving centers like Cairo and Ushak. Carpets featuring central medallions, curving vines, and stylized palmettes became symbols of Ottoman refinement, echoed in manuscript borders, bookbindings, and embroidered textiles.

“As Ottoman power expanded, so too did their textile networks.”

By the late 15th century, Ushak (or Oushak) emerged as the empire’s most renowned weaving center. Situated in western Anatolia, it housed some of the finest weavers in the Ottoman realm. While early Ottoman court carpets emphasized curvilinear designs, Ushak spearheaded a revival of geometric motifs; particularly the ‘Göl,’ a medallion-like form often octagonal and arranged in mirrored or rotational symmetry. Covering the field in endless repetition, these medallions evoked notions of infinity and continuity.

“By the late 15th century, Ushak (or Oushak) emerged as the empire’s most renowned weaving center.”

The Göl motif, alongside Ushak’s distinctive star patterns, reflected both Persian influence and Turkish adaptation. These designs, rendered in lustrous wool, defined the Ushak style and dominated the high-end carpet trade to Europe. Their luminous texture, a result of carefully selected wool and refined weaving techniques, became a hallmark of Anatolian luxury production.

Anatolian Fauna Carpets and Western Fascination

“The resonance of these carpets extended into Western Europe, where they became prized possessions”

The early Ottoman centuries also saw the flourishing of the early Anatolian animal-motif carpets, distinguished by their intricate combat scenes, the most famous being the ‘Dragon and Phoenix’ motif. Introduced via Mongol intermediaries from China, these designs were seamlessly integrated into Islamic art, often reframed within geometric compartments. The resonance of these carpets extended into Western Europe, where they became prized possessions and appeared frequently in Renaissance paintings from the 14th to 16th centuries.

Even as industrialization altered the economics of production, the hand-woven carpet retained its symbolic weight. In rural Anatolia, tribal weavers continued to create kilims and pile rugs with deeply personal motifs: birth symbols, protection charms and fertility emblems, maintaining a lineage of meaning that predated the empires themselves. In urban manufactories, meanwhile, the legacy of courtly design persisted, ensuring that the heritage of Ottoman weaving would endure well into the modern era.

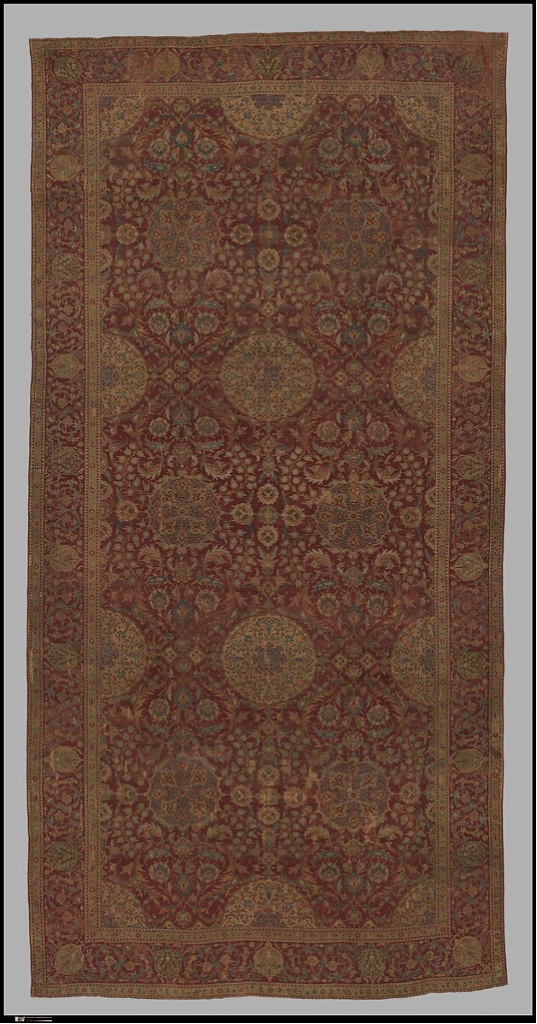

This splendid carpet, with feathery leaves, stylized lotus flowers, and tightly curled cloud-band scrolls, displays characteristics associated with a group of carpets of debated provenance. While the wool and weaving methods of this group are akin to carpets woven in Egypt, their designs probably were produced in Istanbul. Documents reveal that on at least one occasion in 1585, the Ottoman sultan Murad III requested that a number of Cairene weavers, along with a quantity of Egyptian wool, be brought to the court in Istanbul. Such interactions may explain the unexpected combination of materials, technique, and design found in these carpets.

Although Mamluk Cairo fell to the Ottomans in 1517, the city continued to be a major center for artistic production. Using the same materials and techniques as earlier Mamluk carpets, Ottoman court carpets such as this were produced in Egypt for export, primarily to the Ottoman court in Istanbul. The immense scale of this carpet’s drawing suggests it once formed part of an even larger carpet.

This 15th-century carpet in the Museum of Islamic Art – Berlin, showing the battle of the dragon and the phoenix, is one of the most crucial animal carpets of the early Ottoman period that have become known to the present day – disputed to be Armenian!

Medallion Ushak carpets usually have a red or blue field decorated with a floral trellis or leaf tendrils, central medallions, and a border containing palmettes on a floral and leaf scroll, and pseudo-kufic characters. In this example (partially restored), a typical white-ground field pattern is combined with the Medallion Ushak to form a new category of Ottoman carpets. Its triple spots-and-wavy double stripe pattern, called çintamani, appears frequently in Ottoman art from the sixteenth century on tiles, paintings, book bindings, and particularly on textiles and garments. Unlike other white-ground categories, this field pattern never appears in European paintings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Bakhtawar Jamil

Leave a comment