The New Testament is probably one of the most translated texts worldwide, already since Antiquity. Translating holy scriptures was always a great responsibility, since the translator had to convey the form and meaning of the source text as faithfully as possible. Sometimes these translations were accompanied by the original text or yet another translation, in which case we speak of a bilingual or diglot. These multilingual manuscripts are a fascinating source for research for many reasons. First, they allow us to track cross-linguistic influence between the two versions. Second, they illustrate the linguistic realities of Christian communities in the East. Finally, the aesthetic qualities of these multilingual manuscripts are also worth paying attention to.

When producing a manuscript in multiple languages, the scribe had to consciously organize the writing space. Often multiple scribes worked on a single manuscript. The result was sometimes a richly illuminated and calligraphic work of art. In certain cases, we know the name of the scribe, the monastery, and even the year of copying thanks to a colophon. More often, however, we have no clue as to the date or place of production. The two languages are typically written on the same page in parallel columns (though some bilinguals feature one language per page). While one might assume that one language is a direct translation of the other one, this is seldom the case. Yet, the copyist usually tried to align both columns so that the text matches line by line, enabling the reader to compare them easily.

In the following paragraphs I will introduce some biblical manuscripts (chiefly from the New Testament) from the Medieval East that illustrate this phenomenon. The first three manuscripts are studied in the context of the ERC project BICROSS (https://theo.kuleuven.be/en/research/research_units/ru_bible/lemma/bicross-project), which forms the background for this blog post.

Bohairic-Arabic

In medieval Egypt, Coptic was the most important language of the Christian community. Knowledge of Greek had withered, and the Biblical books had already been translated into the Coptic dialects since the second century CE. Arabic, however, gradually supplanted Coptic as the dominant spoken language in Egypt since the seventh and eighth centuries onwards. By this time, the most widespread dialect of Coptic was Bohairic (also called Memphitic in older literature, as it was thought to originate from Lower Egypt, in contrast to Sahidic from Upper Egypt). Bohairic remains the liturgical language of the Coptic Church today, even if it has long died out as a spoken language.

“From the eleventh to fourteenth centuries, we see a surge of the production of bilingual manuscripts containing Bohairic Coptic on the left and Arabic on the right.”

From the eleventh to fourteenth centuries, we see a surge of the production of bilingual manuscripts containing Bohairic Coptic on the left and Arabic on the right. By the ninth century, Arabic had replaced Greek as the preferred ecclesiastical language in centres like Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch. The Arabic is often written in a less ‘pure’ form than the Classical Arabic of the Qur’an, a variety that was coined ‘Middle Arabic’ by Joshua Blau. Interestingly, the Arabic version often corresponds more closely to the Syriac Peshitta (cf. infra) than to the Coptic text. This is because the two columns are seldom translations of each other, although they could influence one another. In many cases, the copyist selected an already existing Arabic translation of the New Testament (one often derived from the Peshitta) and placed it next to the Coptic.

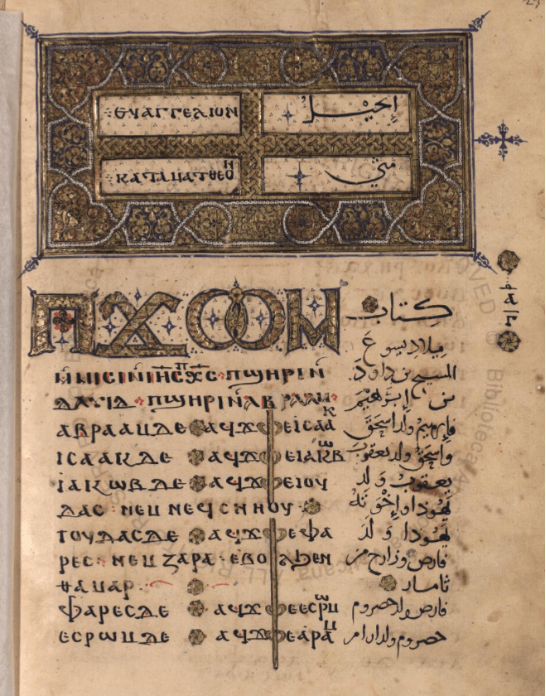

One of the most beautiful Bohairic-Arabic manuscripts is preserved at the Vatican Library. This bilingual, dating from the thirteenth century, displays exquisite calligraphy. In the illustration of the opening of the Gospel of Matthew, the Coptic text takes centre stage and occupies far more space than the Arabic. Intriguingly, the scribe linked the Coptic letter ⲫ of the recurring word ⲁϥϫⲫⲉ ‘he begot’. The Arabic is written in a very neat naskh-type calligraphy and is provided with vowel markings.

Another feature of this manuscript is its beautiful illuminations at the beginning of each Gospel, such as the ornate opening of the Gospel of Luke.

Syriac-Arabic

“An particularly interesting feature of some Syriac-Arabic manuscripts is that the Arabic is written in Karshuni, that is, Arabic written in Syriac script, a practice adopted in Christian communities in the Middle East.”

Syriac is an Aramaic language closely related to Hebrew and Arabic. It is the liturgical language of several Middle Eastern churches, such as the Maronite Church or the Assyrian Church of the East, and is often referred to as ‘Assyrian’ (not to be confounded with the Akkadian dialect written in cuneiform). As a vibrant language spoken throughout the Middle East, Syriac was used early on for New Testament translations. Several translation traditions exist, such as the Harclensis and the Philoxenian, but the most influential and well-known is the Peshitta. This is the version most often encountered in the Syriac column of bilinguals, although there are also bilinguals with the Harclensis version.

An particularly interesting feature of some Syriac-Arabic manuscripts is that the Arabic is written in Karshuni, that is, Arabic written in Syriac script, a practice adopted in Christian communities in the Middle East. As you can imagine, this makes it rather difficult for cataloguers to recognize the bilingual nature of such manuscripts, as at first sight they appear to be entirely in Syriac. It is very possible that many more Syriac-Arabic bilinguals remain unidentified in collections around the world, waiting to be found.

A fine example of a Syriac-Arabic bilingual is MS syr. 42, kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in Paris. Whereas in other Syriac-Arabic bilinguals both columns occupy roughly the same amount of space (as in MS Vat. syr. 23, for instance), here the Syriac column is written in larger characters than the Arabic, suggesting its pre-eminence. This bilingual contains the four Gospels, as well as notes specifying when particular passages are to be read in the liturgy. Such features are shared with lectionaries, manuscripts that arrange selected biblical passages in liturgical order. Another noteworthy aspect is the use of red ink and large hollow letters used to highlight not only the incipit “The Gospel of Mark the Evangelist” (ܐܘܢܓܠܝܘܢ ܕܡܪܩܣ ܡܣܒܪܢܐ), but also the nomina sacra “Jesus” (ܝܫܘܥ), “Messiah” (ܡܫܝܚܐ), and “God” (ܐܠܗܐ). The Arabic mimics this colour scheme only for the incipit, not for the nomina sacra.

Syriac-Sogdian

“However, Christianity was also spread eastwards by missionaries who used Syriac. “

As I mentioned in a previous blog post on the Tocharians, the site of Turfan in the Chinese province of Xinjiang has yielded a wealth of manuscript fragments in multiple languages. Many of these were written in Sogdian, an Iranian language related to Persian that functioned as a lingua franca along the Silk Road. The main religion of that region was Manichaeism, first propagated by the Persian prophet Mani. However, Christianity was also spread eastwards by missionaries who used Syriac. They reached as far as China to spread their version of Christianity, as attested by another bilingual document: a Syriac-Chinese inscription on stone, the so-called Xi’an stele.

Fragments of the New Testament in Syriac-Sogdian bilingual form also survive. In these, Syriac occupies the place of honour on the left, while the Sogdian text appears on the right, written in a variant of the Syriac script.

A Multilingual Manuscript of the Book of Psalms

The final manuscript I want to present is not a New Testament bilingual but a Psalter containing the text of Psalms in no fewer than five different oriental languages (Armenian, Arabic, Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopic). The layout of this manuscript vividly demonstrates how much space each language requires: the Coptic and Armenian columns take up far more room than the others, since their alphabets include both consonants and vowels, whereas languages like Arabic and Syriac use an abjad, which omits most vowels. One can also observe that two different hands contributed to this manuscript; the Ethiopic hand in the final pages is noticeably less skilled than the one at the beginning.

Maxime Maleux

Literature

- Blau, Joshua. 2002. A handbook of early Middle Arabic. Jsai.

- Dickens, Mark. 2009. ‘Multilingual Christian Manuscripts from Turfan.’ Journal of the Canadian Society for Syriac Studies 9 (1): 22–42.

- Griffith, Sidney H. 2013. The Bible in Arabic: The Scriptures of the “People of the Book” in the language of Islam. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Kessel, Grigory (forthcoming), “Syriac-Arabic Bilingual Manuscripts in Parallel Columns: A Preliminary Inventory.” In Language Multiplicity in Byzantium and Beyond, edited by C. Rapp et al. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Metzger, Bruce M. 1977. The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Metzger, Bruce M. 1984. ‘Bilingualism and Polylingualism in Antiquity: With a Check-List of New Testament MSS Written in More than One Language.’ In The New Testament Age: Essays in Honor of Bo Reicke, edited by William C. Weinrich, 327–34. Macon: Mercer University Press.

- Proverbio, Delio Vania. 2000. ‘Per la storia del manoscritto copt. 9 della Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana’ in Rara volumina: rivista di studi sull’editoria di pregio e il libro illustrato 1/2: 19–30.

- Proverbio, Delio Vania. 2012. ‘Per una storia del fondo dei Vaticani Copti’. In Coptic treasures from the Vatican Library: a selection of Coptic, Copto-Arabic and Ethiopic manuscripts, edited by Paola Buzi and Delio Vania Proverbio, 11–19. Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

Leave a comment