“What is fashionable is what one wears oneself. What is unfashionable is what other people wear” – Lord Goring from Oscar Wilde’s An Ideal Husband.

Fashion, as lord Goring quite aptly put it, has always been relative. It is said that when the Greeks first encountered the Persians, they were not only frightened by their formidable military reputation but also by the strange clothing that these foreigners wore. Trousers were seen as utterly alien and the lavish fashion choices of the Persian nobility would become symbols of the foreigner, to be feared and ridiculed.

And yet, behind the elegance and the strange trousers lay a rich tapestry of meaning. These clothes tell of the cultural history of the Persians, from their origins as nomadic horse riders in the Eurasian Steppe to becoming the rulers of a world empire that drew in influences from some of the most ancient cultures on Earth. Clothing in the empire had become far more than simply a way to protect the body but also a symbol of the identity, ideology and status of its wearer.

This article will go over the main clothing types that the Persians made use of, from the most noble men and women of the empire to the common Persian, and uncover the vividly colourful and intricate fashion culture from one of the greatest empires ever seen.

The Court Robe

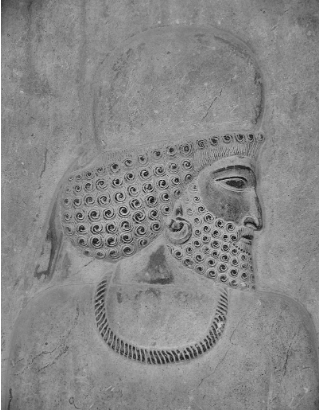

From the reliefs of the palace city of Persepolis to the glazed brick friezes of Susa, the court robe is probably the item of clothing most closely associated with the Achaemenids.

While some sources see the court robe as composing of two separate items of clothing, academic consensus leans towards it consisting of a large rectangle of fabric with an opening for the head and two large openings for the arms. This would be worn over a pair of trousers and would be tied at the waist with a belt. Focused stitching and tucking would then assist in creating pleats in the robe to give it greater volume.

Although it may trace its origins to the Elamite civilisation of south-western Iran, the court robe became the clothing of choice for those of high status. The previously mentioned brick friezes from Susa are a depiction of what is most likely the royal guard, given the intricate decoration of their clothing and the ornate jewellery that they wear, all of whom wear the court robe. The court robe was also the garment of choice for the nobility, as can be seen in tombs such as the Satrap’s Tomb from Sidon, while the murals of Persepolis show courtiers dressed in the court robe escorting foreign dignitaries. The most prominent wearer of the court robe, however, would be the Great King himself. Whether it be in hunting and combat scenes found on seals or in monumental architecture such as the royal tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam and the great palace of Persepolis, the king of kings is almost always shown in the court robe.

Beyond its status as the clothing of high society, the court robe also acquired a symbolic association within the Persianideological framework. At Persepolis, scenes depict a so-called “Hero figure” locked in combat with a mythical beast. This imagery has often been interpreted as a representation of the victory of Order and Truth (Arta in Zoroastrian thought) over Chaos and the Lie (Druj). The fact that the king is also shown wearing the court robe in contexts where such an elaborate garment would have been impractical, such as combat or hunting, further underscores its close connection to royal power and the ideological role of the king as guarantor of cosmic order.

As can be expected of a garment with such lofty status, the court robe was often a work of art in its own right. The robe would be highly decorated with intricate designs, as can be seen with the royal guards at Susa, alongside having appliqués of gold or semi precious stones in the shape of lions and other beasts woven into it. The pinnacle of the court robe’s artistry would be, rather unsurprisingly, the robe worn by the Great King, with a study concluding that, when factoring in the materials and the labour required to produce it, the royal robe would be worth millions of euros today.

In terms of headwear, Achaemenid art shows two main types worn with the court robe: headbands or circlets, and the mitra. The headbands ranged from knotted fabric dyed in vivid colours to more formal metal circlets, such as those worn by the royal guards in the Susa frieze. The mitra, by contrast, was a distinctive soft headpiece that could be smooth or fluted in design, fashioned from cloth or occasionally metal. Its form varied in height and elaboration, with taller or more ornate examples reserved for higher-ranking wearers, reinforcing distinctions of status within the court. The mitra is also another instance of Achaemenid adoption of Mesopotamian customs, as similar headwear can be seen in cultures such as the Assyrians.

The court robe, along with its accompanying headwear, was a symbol of empire, a representation of the Achaemenids as rulers of the world, guardians of cosmic order, and heirs to the civilisations that came before them. Yet this was only one side of Persian identity, with the other lending itself to a very different kind of apparel.

The Rider’s Outfit

“At their core, the Persians were a horse-riding people … This lifestyle shaped a wardrobe built for movement, endurance, and adaptability”

At their core, the Persians were a horse-riding people, descended from nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppe who settled on the Iranian plateau in the 8th century BCE. This lifestyle shaped a wardrobe built for movement, endurance, and adaptability. Under the Achaemenids, this practical steppe attire was elevated into a marker of prestige and cultural identity: the Rider’s Outfit.

The Rider’s Outfit consisted of several components. At its base was a long-sleeved, knee-length tunic, typically belted at the waist. Then came the customary Persian trousers, a striking novelty to the Greeks, with some examples incorporating attached footgear to form a hybrid of leggings and slippers. Completing the ensemble was the most distinctive element, a long sleeved full-length coat known to the Greeks as the kandys and to the Persians as the gaunaka, often worn draped over the shoulders with the arms sometimes kept within the coat instead of the sleeves.

“The gaunaka itself occupied a place of great prestige within the Achaemenid wardrobe. In the royal court, only the king and high-ranking nobility were permitted to wear it”

Although the Greeks referred to this style as the “Median dress”, often using “Mede” as a blanket term for Persians and related peoples, the Rider’s Outfit was in fact far broader in scope. Variations of it were worn across the Iranic world, from the Bactrians in the east to the nomadic Scythian tribes of the steppe. It was, in essence, a pan-Iranic attire, shaped by the demands of a nomadic, horse-riding lifestyle, and under the Achaemenids, it became a symbol of shared heritage and imperial identity.

The gaunaka itself occupied a place of great prestige within the Achaemenid wardrobe. In the royal court, only the king and high-ranking nobility were permitted to wear it, setting it apart as a garment of distinction. This exclusivity is illustrated in depictions of figures such as Payava of Xanthos, a Lycian dynast under Persian rule, whose tomb reliefs show him clad in the gaunaka, or the occupant of the Karaburun tomb, who was shown to wear a lynx fur lined gaunaka. The garment was also among the most prestigious of royal gifts: richly coloured and embroidered with gold, a gaunaka bestowed by the king signified exceptional honour.

When addressing the monarch, nobles who wore the gaunaka would slip their arms inside the long sleeves so that their hands were covered. According to Xenophon, this gesture symbolised submission, showing that the wearer could not take up arms against the king; refusal to do so was considered a grave insult.

Even though many gaunakas were lavishly ornamented, the most meaningful example may have been the simplest. Upon his coronation, the new king is said to have worn the gaunaka once belonging to Cyrus the Great, thereby presenting himself as heir to the founder’s legacy. Only after this symbolic act would he don his own richly decorated garment, marking the beginning of a new reign while affirming continuity with Persian horse-riding heritage.

In art, the king is often depicted in the ceremonial court robe, even in scenes of combat or the hunt. Yet in reality, he almost certainly wore the Rider’s Outfit, which was both more practical and a conscious statement of Persian identity. The royal version of this outfit was no less magnificent than the court robe, decorated with intricate patterns and rich embellishments. One distinctive feature, noted by Xenophon and echoed in later artistic traditions such as the Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii, was a tunic dyed entirely purple except for a single white stripe running down the centre, a striking emblem of the unique and elevated status of the King of Kings.

As with the court-focused wardrobe, the Rider’s Outfit had its own distinctive headgear, reflecting both the Persians’ nomadic origins and the practical needs of life in the saddle. One common item was a round wool felt cap, regarded as an ancestor of the kolah namadi still worn in parts of Iran today. These caps could be reinforced with metal or fitted with attachment points for ornamental additions, balancing function and display. Another option was a wrapped headscarf, covering the head and neck—a style deeply rooted in steppe traditions, providing both warmth and protection against dust and wind.

“The most iconic, however, was the so-called “Phrygian cap” of Greek sources, better understood as the Persian tiara.”

The most iconic, however, was the so-called “Phrygian cap” of Greek sources, better understood as the Persian tiara. Variants of this headpiece were worn widely across Iranic cultures, from Persians to Scythian nomads. In its Persian form, it was typically a soft, rounded cap secured at the forehead with a brightly coloured cord, often with long flaps that could be tied across the mouth for protection in harsh conditions. Status was conveyed in subtle details: high-ranking nobles were permitted to display the knots of their cords at the front, while only the Great King himself could wear the pointed version of the tiara (see reconstruction on page x). Like the gaunaka, this cap also entered the sphere of royal gift-giving, with Xerxes recorded as bestowing a gold-embroidered example as a mark of honour.

Together, these forms of headwear reveal how the Rider’s Outfit embodied both prestige and practicality, tying Persian aristocracy back to its steppe heritage even within the sophisticated world of the empire.

Together, the Rider’s Outfit and its associated headgear embodied a balance of prestige and practicality. Where the court robe represented the Achaemenids’ role as guardians of empire and cosmic order, the Rider’s Outfit recalled their nomadic origins, reaffirming identity through clothing suited for both the saddle and the court. Yet clothing was not only a language of power among men. Just as garments such as the gaunaka or the tiara conveyed hierarchy, loyalty, and royal favour, so too did women’s dress serve as a vital marker of rank and splendour within the empire. From noblewomen of the court to the queen herself, female attire reflected both the grandeur of Persia and the social identity of its wearer.

Gentlemen… and Ladies?

Although women appear less frequently than men in Achaemenid art, the glimpses we do have reveal no less splendour. From reliefs and funerary monuments to scattered Greek accounts, enough survives to piece together the fashions of elite Persian women. Like their male counterparts, their garments were never purely decorative: they signalled rank, wealth, and participation in the cosmopolitan traditions of the empire. Through finely pleated dresses, ornate veils, and jewelled coronets, the attire of women reflected the same interplay of identity and prestige that defined the clothing of Persian men, yet with forms and symbols uniquely their own.

“As with men, the clothing of aristocratic and royal women would be highly ornate, with complex embroidery, golden appliqués, and the frequent use of jewellery such as bracelets, earrings, and necklaces.”

The garments worn by elite women closely mirrored the court robe tradition of men, showing the pervasiveness of Elamite fashion trends in the Persians’ more sedentary attire. The principal garment was an ankle-length dress, often pleated or folded and finished with richly decorated hems. A waist-length veil was a frequent addition, draped behind the head to the waist or tied in a scarf-like fashion. Full facial veiling, however, appears to have been rare, suggesting that concealment was not the norm in Achaemenid practice.

As with men, the clothing of aristocratic and royal women would be highly ornate, with complex embroidery, golden appliqués, and the frequent use of jewellery such as bracelets, earrings, and necklaces. Fabrics were typically wool or imported silk, dyed in a spectrum of vivid colours that marked wealth and status, echoing earlier Mesopotamian fashions while also displaying the empire’s cosmopolitan character.

Hair was typically worn long, and headwear seems to have played a prominent role in signalling rank. Noblewomen often wore coronets or tiaras, sometimes topped with crenellations, from which the veil could be attached. In Achaemenid art, the scale and decoration of these coronets appear to have functioned as markers of hierarchy, distinguishing high-ranking women of the court from those with more modest attire.

Just as the court robe or rider’s outfit embodied hierarchy and imperial identity for Persian men, the attire of women performed a parallel role within the Achaemenid world. Through jewelled coronets, veils, and richly dyed dresses, elite women’s garments proclaimed not only wealth and status but also their position within the social and ceremonial life of the empire. In the splendour of their dress, they stood as visible extensions of dynastic prestige and the cultural richness of Persia, reflecting the same ideals of order, hierarchy, and legacy that lay at the heart of Achaemenid power.

Colours and Materials

One of the features of Persian clothing that most impressed the ancient Greeks was its sheer richness. This was not only due to the embroidery, jewellery, and appliqués that adorned garments, but also to the dazzling colours in which they were dyed.

“One of the features of Persian clothing that most impressed the ancient Greeks was its sheer richness.”

Colour itself could function as a marker of wealth and status just as much as cut or ornament. The rarity and expense of dyes meant that brilliant hues were restricted largely to the elite. Most commoners wore garments in the natural tones of their materials, such as undyed wool or felt, or in muted colours derived from easily sourced dyes, for instance, the browns produced from walnut husks. Some shades, like red from the madder root, were technically available to all, but were more commonly seen among the wealthier classes. Indigo blue also seems to have carried a higher status, requiring imported dye for production.

The most prestigious and expensive dyes were yellow and purple. Yellow, produced from saffron, was prized for its brilliance, but extracting the threads from the crocus sativus flower was both time-sensitive and labour-intensive, making it a luxury colour reserved for the wealthy. Purple, sourced from the murex sea snail of the Mediterranean, was even more exclusive. Not only was the harvesting process difficult, but the yield was minuscule: one study estimates that 12,000 snails were required to produce just 1.4 grams of dye. As a result, purple was reserved for the very highest ranks of society and even a small band of it on a hem or sash signalled immense prestige.

Thus, while the elites of the empire dazzled in saffron yellows and imperial purples, most Persians lived in a more plain world of undyed wool and simple browns. Yet even among the lower classes, colour had meaning: the occasional cord, sash, or brightly dyed belt could stand out as a rare and deliberate statement. To see how this played out in practice, we now turn to the clothing of the common people.

From the Palace to the Day to Day

So far, this article has focused on the fashions of Achaemenid elites, garments laden with prestige, symbolism, and royal identity. Yet to understand Persian clothing more broadly, we must also look at the everyday dress of ordinary people, whose garments were shaped less by ceremony and more by practicality, climate, and local resources.

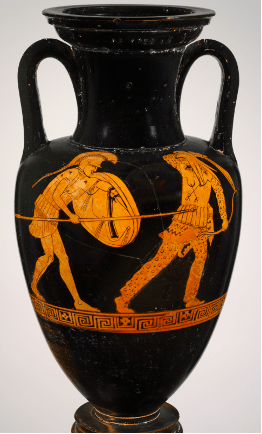

Greek vase painting, especially after the Persian Wars, provides one of the more unexpected sources for Persian dress. Pottery such as the Eurymedon vase and the Nolan amphora (shown below) depict Persian soldiers clad in tunics and their characteristic trousers. In essence, the regular Persian man wore the same style of attire as the Rider’s Outfit seen among elites.

The felt cap, too, appears to have been so widespread that Greeks considered it a standard Persian hallmark, as seen in examples like the Athenian drinking mug shown below:

The most direct evidence, however, comes from the Chehrabad salt mine in northern Iran, where miners were buried by cave-ins from the Achaemenid through the Sassanian periods. Thanks to the preservative qualities of the salt, the bodies, and their clothing, survived. The garments of the Achaemenid-period miners consisted of woollen trousers and tunics, largely undyed, though with occasional coloured details. One miner, known as Salt Man 3, wore red cords and a multi-coloured belt, hinting that even among workers, clothing could carry small markers of personal or social significance. In colder climates, people likely wore heavier cloaks or garments resembling the gaunaka, particularly those who lived a semi-nomadic, horse-riding lifestyle.

The clothing of common women is harder to reconstruct, since they appear only rarely in the sources. Yet, by analogy with men’s dress and with neighbouring traditions, we can sketch some possibilities. In sedentary regions, women likely wore long, straight-cut robes similar in form to those of their aristocratic counterparts, paired with simple veils or shawls for relief from the heat. These garments would have been markedly less ornate, with limited use of colour or decoration beyond small details such as a cord or belt, and would have been accompanied with a simpler collection of jewellery. In nomadic or pastoralist communities, women may have worn clothing closer to that of the Scythians, such as belted tunics over trousers and thick coats during colder months, reflecting both cultural exchange and the practical demands of a horse-riding life.

Whether for miners deep in the salt hills of Chehrabad and farmers on the Iranian plateau, or women from either cities and towns or nomadic camps, everyday Persian clothing was simple, functional, and adapted to circumstance.

The Wardrobe of Empire

The clothing of the Achaemenid Persians was a fascinating example of how fashion can tell the story of a people. One can see how, even though the Persians absorbed and incorporated the trappings and styles of the ancient cultures they encountered as they created their empire, they fiercely held onto their nomadic heritage, elevating and displaying their nomadic clothing with pride. In doing so, they crafted a visual language that was at once practical and symbolic, linking the court to the steppe, the individual to the empire, and the present to the past. Persian dress was not only a matter of appearance, but a statement of belonging, hierarchy, and identity, one that continues to remind us of how powerfully clothing can embody the soul of a civilisation.

Milo Reddaway

Further Reading

- Collins, A.W., 2012. The royal costume and insignia of Alexander the Great. American Journal of Philology, 133(3), pp.371-402.

- Ebbinghaus, S., Eremin, K., Lerner, J.A., Nagel, A. and Chang, A., 2023. An Achaemenid God in Color. Heritage, 7(1), pp.1-49.

- Goldman, B., 1991. Women’s robes: the Achaemenid era. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 5, pp.83-103.

- Llewellyn-Jones, L., 2022. Persians: The age of the great kings. Hachette UK.

- Llewellyn-Jones, L., 2020. The Royal* Gaunaka: Dress, Identity, Status and Ceremony in Achaemenid Iran. Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia, Oxford, pp.248-257.

- Messerschmidt, W., 2021. Clothes and Insignia. A Companion to the Achaemenid Persian Empire, 2, pp.1075-1086.

- Stöllner, T., Aali, A., Boenke, N., Davoudi, H., Draganits, E., Fathi, H., Franke, K.A., Herd, R., Kosczinski, K., Mashkour, M. and Mostafapour, I., 2024. Salt Mining and Salt Miners at Talkherud–Douzlākh, Northwestern Iran: From Landscape to Resource-Scape. Journal of World Prehistory, 37(2), pp.61-140.

- Vanden Berghe, I. and Grömer, K., 2022. Sassanid Dyes from Ancient Persia–Case Study Chehrābād in Northern Iran. In Ancient Textile Production from an Interdisciplinary Perspective: Humanities and Natural Sciences Interwoven for our Understanding of Textiles (pp. 53-68). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Leave a comment