If one talks about the decipherment of Linear B, one is immediately reminded of the architect Michael Vetris and his partner John Chadwick, who in 1952 discovered that the language behind Linear B was actually an old dialect of Ancient Greek, known as Mycenaean Greek.1

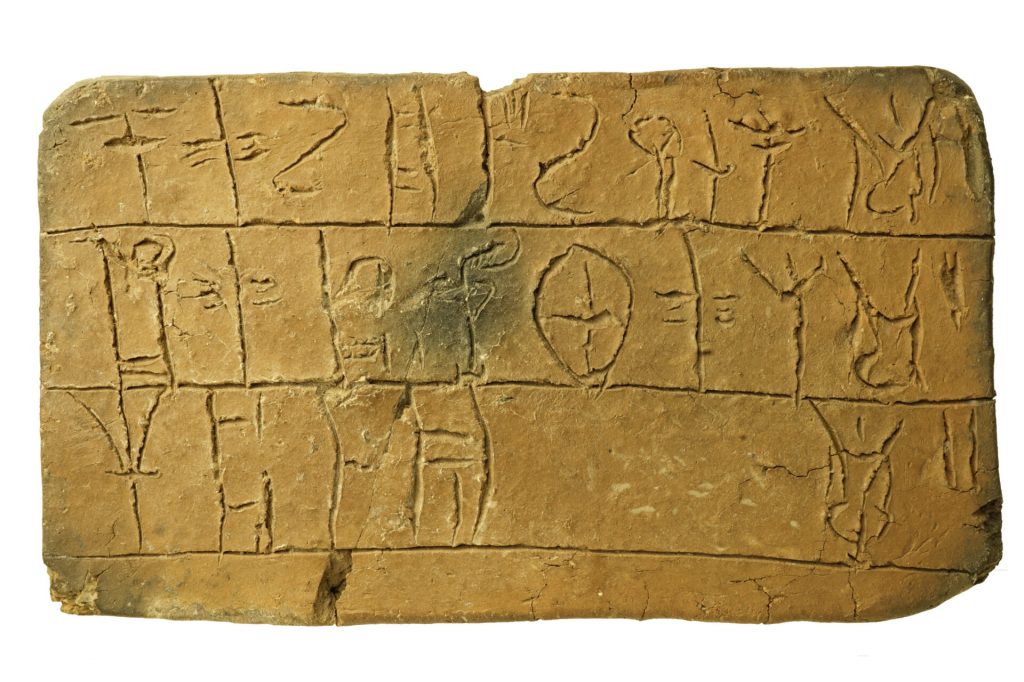

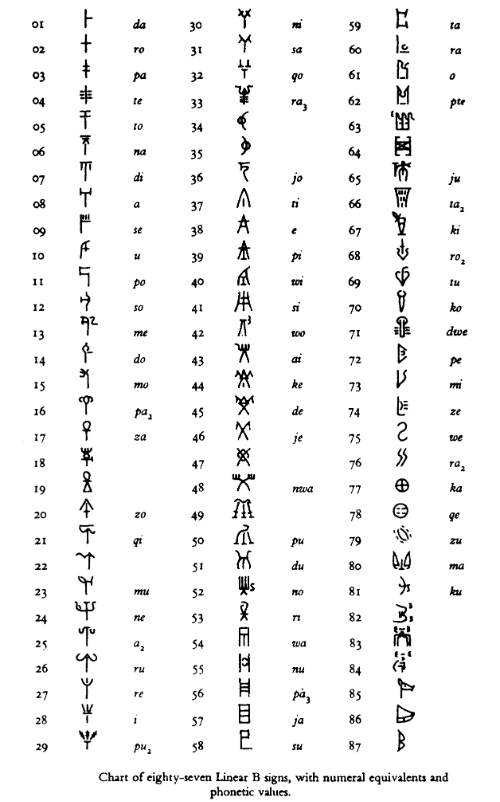

The script which served as the medium of Mycenaean Greek was syllabic. Instead of representing letters, the symbols used in a syllabic script represent syllables. Each sign stands for a consonant, followed by a vowel. A place name like Knossos, for example, would be spelled out as KO-NO-SO. Such a syllabic system can still be found around the world today (e.g. Japanese).2

“The problem with this focus on Ventris, is that the narrative overshadows one crucial step in the road to solving the puzzle: Alice Kober.”

The discovery that Greek was the language lurking behind Linear B sent a shockwave throughout the academic world. Moreover, the fact that this was done by an architect, and not an academically trained linguist/classicist, must have felt like an embarrassing slap in the face for numerous ‘professionals’ who had likewise poured decades of blood, sweat and tears into cracking the ‘Mycenaean code’.

The problem with this focus on Ventris, is that the narrative overshadows one crucial step in the road to solving the puzzle: Alice Kober. If not for her, Mycenaean studies wouldn’t be where it is right now.

Besides Classics, Kober showed a keen interest in all types of subjects, enrolling in courses such as math and natural sciences. In 1932 she started her academic career at the Classics Department at Brooklyn College. She would work here until here untimely death in 1950. During these years, she published her ideas and findings on the enigmatic and mysterious Cretan writing systems.3

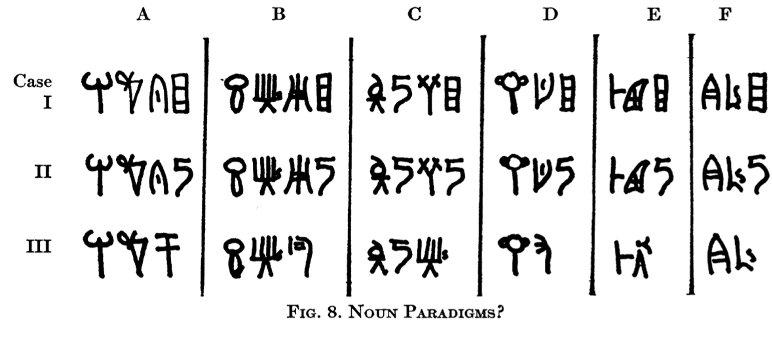

The observation that gained priority in Kober’s work was the apparent presence of inflection in the writings of the Mycenaeans. While digging through the archives of Linear B tablets, Kober came across several similar sign sequences that differed only in their word endings. This discovery led to lists such as the one given below:

The six different sign sequences show matching signs at the beginning yet differ at the end. For Kober, these discrepancies were symptomatic of inflection: the sign sequences were nouns, and the variable endings reflected their appearance in different cases.3

Inflection is the use of declensions to indicate the function of a word in a sentence. In modern languages this is, for example, still the case in German, which has four declensions for its nouns—nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative—each serving a different function in the sentence.

The importance of this discovery must be seen in light of the fact that the language lurking behind Linear B was still undiscovered. It would be several years before Ventris and Chadwick had their eureka moment. Although the meaning of these sign-sequences was still unknown, as were their phonetic values, Kober had already found solid proof that the language contained inflection. This major breakthrough served as a stepping stone for Ventris and Chadwick.

Michael Ventris continued to expand this roster of inflections and gradually assigned phonetic values to each sign. By using the ideograms to identify the meanings of certain words, and by applying a series of remarkably sophisticated deductions and educated guesses, Ventris managed to create an intricate upward spiral of decipherment that ultimately revealed the language behind Linear B to be none other than Mycenaean Greek.

If it had not been for Kober, however, it is very likely that Ventris would not have been able to decipher Linear B. Unfortunately, Alice Kober did not live to see the Mycenaean script deciphered.

Benjamin Van Noordenne

Sources:

- Chadwick, J. (1970). The decipherment of Linear B (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Voight, L., “A. Professor Alice Kober”, Brown University. Consulted through https://www.brown.edu/Research/Breaking_Ground/bios/Kober_Alice.pdf.

- Hooker, J. T. (1980). Linear B: An introduction. Bristol Classical Press.

Leave a comment