Although the history of Bactria and the Indo-Greek kingdoms remains largely obscure, our knowledge of early Bactrian history is somewhat more substantial than that of later Bactrian or Indo-Greek developments. This disparity is largely due to the nature of the surviving source material. Written sources for the region are extremely limited, and most rulers are not mentioned at all. Nonetheless, a few of the most significant kings—such as Eucratides and Menander Soter, the most prominent figures of the Bactrian and Indo-Greek realms—do receive brief mention in ancient literary sources. Fortunately, this also applies to some of Bactria’s earliest rulers. This article focuses on those early kings: the Diodotids, who first secured Bactrian independence from the Seleucid Empire, and the early Euthydemids, who consolidated and reaffirmed that independence in the following decades.

While it was stated that we know comparatively more about the early history of Bactria, this does not mean that key developments—such as its transition to independence—are clearly understood. Scholarly debate on these issues remains active on multiple fronts. Bactria’s independence should be situated around 250 BCE, however, contradicting literary sources result in uncertainty on the exact date.

Our principal source on Bactrian independence is Justin, whose Epitome was based on the now-lost Histories of Pompeius Trogus who wrote in the time of Augustus.1 Justin discusses Bactrian independence in connection with developments in Parthia, noting that the Parthians and the Bactrians seceded from Seleucid rule around the same time. In dating this secession, he states that it occurred in the year when Vulso and Regulus were consuls—corresponding to 256 BCE. However, in the same sentence, he also claims that it took place during the reign of Seleucus II (246-225 BCE), who only ascended the throne in 246 BCE. Justin further remarks that internal struggles within the Seleucid Empire, namely the conflict between Seleucus II and Antiochus Hierax, created the opportunity for revolt in the eastern territories—an observation that reinforces the view that Bactrian independence was achieved under Seleucus II’s rule.

“Only at a later stage, either Diodotus himself or his son Diodotus II began issuing coins in their own name, thereby completing the transition to a fully independent coinage.”

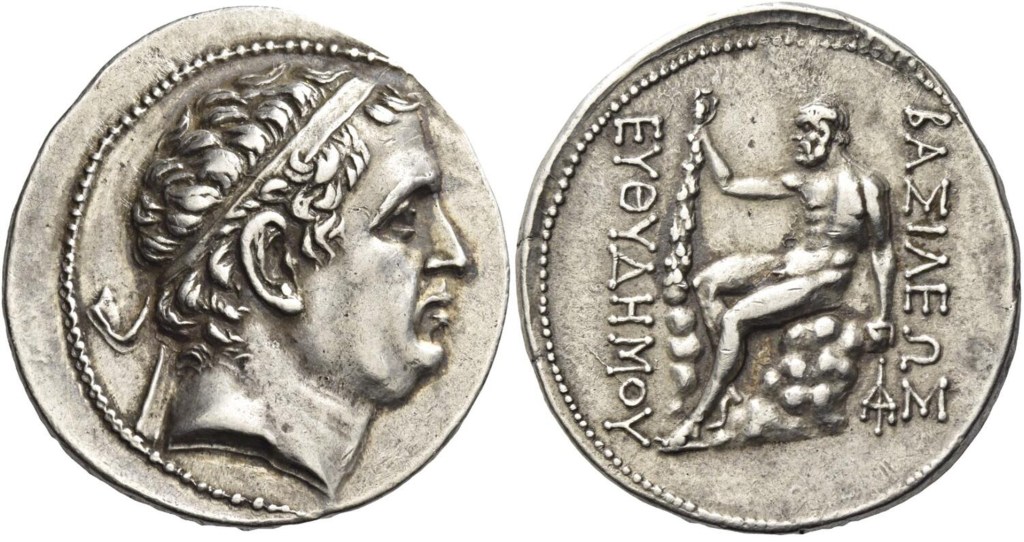

Another point of discussion, and a major topic in current scholarship, concerns some of the earliest issues of independent Bactrian coinage—or, at least, coins that have long been interpreted as such. According to the traditional view, Diodotus I did not immediately strike coins that openly asserted his independence from Seleucid rule. Instead, he is thought to have first issued coins bearing his own portrait and a new depiction of a deity—the so-called ‘Thundering Zeus’—while still using the name of Antiochus (interpreted in this view as the Seleucid ruler Antiochus II who ruled 261-246 BCE) in the coin legend (Figure 1). Only at a later stage, either Diodotus himself or his son Diodotus II began issuing coins in their own name, thereby completing the transition to a fully independent coinage.

This view was, until recently, regarded as the most likely reconstruction of events. However, Jens Jakobsson (2010) has challenged this interpretation by arguing that the so-called ‘transitional types’—those still bearing the name Antiochus—should instead be attributed to a third Diodotid ruler named Antiochus, who reigned after Diodotus I and II. While not all scholars have readily embraced this reinterpretation, Jakobsson’s hypothesis has gained support through the research of Zeng (2013), who demonstrated die-links between these Antiochos coins and certain issues of Euthydemus I, the usurper of the Diodotid throne.

Die-links can offer a wealth of information and merit a detailed explanation. They can be instrumental in establishing the sequence of coin production and arise directly from the ancient minting process. Ancient coins were struck by placing a piece of metal, or ‘flan’, between two hand-engraved dies—one for the obverse and one for the reverse—and then striking it forcefully with a hammer, thus imprinting the designs of the dies onto the coin. This method inevitably caused the dies to wear, develop faults, or break over time, requiring their periodic replacement. Since each die was engraved by hand, no two were exactly alike, and repeated hammering also introduced slight variations in individual coins. As a result, every struck ancient coin is unique. By identifying which coins share the same dies, numismatists can reconstruct patterns of production: which dies were used early or late, and which obverse dies were paired with which reverse dies.

Most die-links occur within the production of a single coin type issued by the same king. Only rarely is the same die used in the coinage of two different rulers. When such a case is identified, it provides crucial information about chronology and succession—especially in a field as obscure as Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics. The die-links identified by Zeng suggest that the Antiochos coins were minted close in time to the issues of Euthydemus I. This proposed chronology stands in contrast to the traditional view, which places the Antiochus series at the very beginning of independent Bactrian coinage.

While scholarly debate continues regarding the number of Diodotid rulers, literary sources inform us that the first dynasty of Bactria came to an end with the usurpation of Euthydemus I, probably around 220 BCE.2 Compared to most Bactrian kings, we possess considerably more information about Euthydemus, and it is clear that he was one of the most significant rulers of the Bactrian kingdom, likely enjoying a lengthy reign.

“Antiochus’ goal was to reclaim the eastern satrapies that had broken away from Seleucid control decades earlier, and Bactria—with its wealth and strategic position—was a prime objective.”

The main reason we have even a partial picture of Euthydemus’ reign is due to the eastern expedition (anabasis) of the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III (223-187 BCE), which brought him into direct conflict with the Bactrian king. Antiochus’ goal was to reclaim the eastern satrapies that had broken away from Seleucid control decades earlier, and Bactria—with its wealth and strategic position—was a prime objective.

The account of this episode in Polybius (lived second century BCE) provides the following information: When Antiochus III arrived in Bactrian territory in 208 BCE, he was informed of the location of Euthydemus’ cavalry—10,000 strong—stationed at the Arius River (the modern Hari River), with the aim of preventing his crossing.3 Antiochus immediately directed his troops toward the enemy, who were three days’ march away. As he neared their position, he broke off from his main army, taking with him his cavalry, light infantry, and a sizeable contingent of peltasts.

Antiochus had been informed that although the Bactrian cavalry guarded the river during the day, they withdrew at night to take shelter in a nearby town. This intelligence allowed him to seize the opportunity to cross the river unopposed, waiting patiently for the right moment. Once his forces had successfully crossed, the Bactrians soon discovered the incursion and came out in force to confront the Seleucid troops.

“In response to the charging Bactrian cavalry, Antiochus took some of his elite cavalry and personally led a charge to engage the enemy head-on, while the rest of his troops moved into their standard battle formations.”

In response to the charging Bactrian cavalry, Antiochus took some of his elite cavalry and personally led a charge to engage the enemy head-on, while the rest of his troops moved into their standard battle formations. The ensuing clash of cavalry, joined by ever-growing numbers on both sides, must have been a brutal spectacle. Antiochus is said to have thrown himself into the heart of the fighting, leading by example. This was not without risk, however, and he carried a lasting souvenir from his heroics: during the battle he was struck in the mouth, losing several teeth, while his horse was killed beneath him. Ultimately, one of his officers led a decisive charge that broke the Bactrian line and caused their morale to collapse. The Bactrian forces fled the battlefield in disarray, and Euthydemus was forced to retreat and take refuge in the city of Bactra (modern-day Balkh).

Antiochus subsequently laid siege to Euthydemus in Bactra—a siege that would ultimately be resolved through a negotiated peace between the two kings.4 Our knowledge of this siege is limited, but Polybius ranks the siege of Bactra alongside those of Tarentum (212 BCE), Corinth (146 BCE), and Carthage (149–146 BCE), demonstrating its importance.5 What we do know suggests that although Antiochus won a significant victory in the field, he was unable to breach the city’s defenses easily, and time was pressing: his eastern campaign was not solely aimed at bringing Euthydemus’ Bactria back into the Seleucid sphere, but also extended beyond it. As a result, peace negotiations were initiated.

Unsurprisingly, Euthydemus was unwilling to relinquish his kingdom or royal title. He argued that it had not been he who rebelled against the Seleucid state, but rather the Diodotid dynasty—the very rulers he had overthrown. Furthermore, he claimed that his kingdom served a useful purpose for the Seleucids, as it bordered lands inhabited by fierce nomadic tribes, whom he kept at bay—thus also protecting Seleucid territory.

Negotiations continued for some time and were ultimately brought to a successful conclusion thanks in part to the role of Euthydemus’ son, Demetrius, who made a favourable impression on the Seleucid king. As a result, Euthydemus was allowed to retain his royal title, and Antiochus even offered one of his daughters in marriage to Demetrius, thereby solidifying their new alliance. However, Euthydemus was also required to make certain concessions. His corps of war elephants was incorporated into the Seleucid army, and Antiochus heavily provisioned his troops with supplies from Bactria before continuing his campaign further east.

A few reflections can be added to Polybius’ account. While it provides valuable insights into early Bactrian history, it also raises several questions. For instance, although we are informed that a treaty was concluded between the two kings, its exact terms remain unclear. It appears likely that, although Euthydemus was allowed to retain his royal title, the agreement did not constitute a treaty between equals. The fact that he was required to hand over his elephant corps to Antiochus may suggest a subordinate status—one in which Euthydemus functioned as a client king who retained de factoindependence but technically remained a vassal of the Seleucid monarch.

Furthermore, while Polybius states that a marriage alliance was arranged—Demetrius was to wed one of Antiochus’ daughters—it remains uncertain whether this marriage ever took place. If it did, it would imply that Seleucid royal blood may have entered the lineage of the Bactrian kings, at least until the last descendants of Demetrius ruled—whoever they may have been. The family relationships among the Bactrian kings are notoriously obscure, despite the attempts of many scholars and enthusiasts to reconstruct dynastic genealogies.

“The kingdom of Bactria had weathered a defining moment that threatened its very existence.”

Whatever the answer to these questions may be, Polybius provides us with one of the most detailed surviving accounts of Bactrian history. His narrative offers a valuable glimpse into the relationship between the Seleucid Empire and the Bactrian kingdom. More importantly, it records how the Bactrian kingdom survived a confrontation with one of the most powerful rulers of the Hellenistic age—perhaps even sealing a dynastic alliance in the process. The kingdom of Bactria had weathered a defining moment that threatened its very existence.

With roughly the first half-century of an independent Bactria now covered, the next instalment of the series will turn to the successors of Euthydemus I, beginning with his son, the already-mentioned Demetrius I. The following decades witnessed several pivotal developments in Bactrian and Indo-Greek history: conquests extending south of the Hindu Kush and culminating in the formation of the Indo-Greek kingdoms; the fragmentation of the realm; and the introduction of numerous radically innovative coin types. Join us in the next installment as we follow Demetrius I and his successors through an era of conquest, innovation, and transformation!

Harald Blot

Primary Sources and Literature:

Primary Sources:

- Justinus, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 41.4.1-20

- Polybius, Histories 10.49

- Polybius, Histories 11.34

- Polybius, Histories 29.12

Literature:

- Bopearachchi, O., Monnaies gréco-bactriennes et indo-grecques: catalogue raisonné, 1991, Paris.

- Bordeaux, O., Les Grecs en Inde: politiques et pratiques monétaires, 2018, Bordeaux.

- Glenn, S., Money and power in Hellenistic Bactria, 2020, New York.

- Holt, F., Thundering Zeus: the making of Hellenistic Bactria, 1999, Berkeley.

- Holt, F., Lost world of the golden king: in search of ancient Afghanistan, 2012, Berkeley.

- Hoover, O., Handbook of coins of Baktria and ancient India: including Sogdiana, Margiana, Areia, and the Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and native Indian states south of the Hindu Kush, 2013, Lancaster.

- Jakobsson, J., “Antiochus Nicator, the third king of Bactria?.” Numismatic Chronicle, Vol. 170, 2010, 17-33.

- Jakobsson, J., “Dating Bactria’s independence to 246/5 BC?.” In The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world, ed. Rachel Mairs, 499-509. New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Mairs, R., “Greek inscriptions and documentary texts and the Graeco-Roman historical tradition.” In The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world, ed. Rachel Mairs, 419-29. New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Mairs, R., ed. The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world, 2021, New York.

- Senior, R., “The Indo-Greek and Indo-Scythian king sequences in the second and first centuries BC,” Journal of Oriental Numismatic History, Vol. 179, 2004, pp. 33-56.

- Strootman, R., “The Seleukid empire.” In The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek world, uitgegeven door Rachel Mairs, 11-37. New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Zeng, C., “Some notable die-links among Bactrian gold staters.” The Numismatic Chronicle, Vol. 173, 2013, 73-8.

Leave a comment