“For my lord Marduk I made it an object fitting for wonder, just as it was in former times”

-Nbp 1 i 30, transl. Andrew George1

Visible from miles away arose the crown jewel of Babylon’s cityscape, the Etemenanki, the symbol par excellence of the Mesopotamian city’s undeniable power. Dedicated to the supreme god Marduk, the ziggurat functioned for the Babylonians as the ultimate proof of their might and devotion toward the divine, while for others it symbolized the city’s arrogance. The massive structure firmly imprinted itself into the shared memory of Mesopotamia, the Middle East and even Europe for centuries to come. Unfortunately, age hasn’t been kind to the ziggurat, with nothing more than rubble remaining on the place where once the embodiment of Babylon’s universal aspirations stood. This article wishes to address the monument, its history, significance, and the problems encountered in researching the subject.

Historical Background: The Ziggurat

The ziggurat is probably one of the most recognisable types of buildings that dotted the ancient landscape of modern-day Iraq, with a history stretching back to the third millennium BCE. It is a pyramid-shaped structure made up of terraces of decreasing size toward the top, which was crowned with a shrine. The name ziggurat comes from the Akkadian word zaqārum, which means “to build high.” According to some researchers, this building type reflects the initial religious practices of the Mesopotamians, who worshipped their gods on hilltops and mountains. Accordingly, the ziggurat was an attempt to recreate this geographical feature on the flat plains of Iraq. The most obvious explanation for wanting an elevated place of worship is to come nearer to the divine world. It was, in fact, believed that these structures were not only places of sacrifice and worship, but quite literally the abodes of the gods. The peoples of the Abrahamic religions later interpreted this attempt to come nearer to God as hubris, however, as clearly reflected in the story of the Tower of Babel (cf. infra).

The ziggurat must have invoked a sense of mystery and reverence among the townsmen, as its height and mass clearly marked it out from the rest of the city. The ziggurat reached its classical form during the time of the Kingdom of the Ur III dynasty (c. late 22nd–21st century BCE), with one magnificent example still standing, remarkably well preserved, at the capital Ur. It was commissioned by King Ur-Nammu (r. c. 2112–2094 BCE) and completed by his successor Shulgi (r. c. 2094–2046 BCE). Soon enough, the ziggurat became one of the defining features of every noteworthy Mesopotamian city from north to south, with about nineteen discovered in sixteen cities by archaeologists. The most famous of them all would arise in Babylon, however—quite unsurprising, given the city’s central role in ancient history.

The Building of the Etemenanki

The Etemenanki towered above Babylon in a vast enclosure north of the Esagila, the city’s main sanctuary dedicated to the patron deity Marduk. Its name came from the Sumerian É.TEMEN.AN.KI, which means “The Temple of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth”. Although references to the Esagila can be traced back to the time of Hammurabi’s Amorite dynasty (c. 1894–1595 BCE), the adjoining ziggurat is only positively attested for the first time in written documents during the Kassite period (c. 1595–1155 BCE). Such an early reference to the ziggurat might be conjectured from Tintir IV, a list of Babylon’s temples, known through a copy of an original which perhaps dates back to Nebuchadnezzar I’s reign (r. 1125-1104 BCE). Another argument for tracing its lineage to the Middle Babylonian period can be deduced from the Enūma Eliš, the city’s creation epic, of which a Middle Assyrian copy refers to the tower.2 Von Soden has placed the responsibility for commencing the construction works with Nebuchadnezzar I, claiming that only this king wielded enough power and amassed sufficient wealth to fund such a megastructure.3 Andrew George, however, has significantly extended the list of potential candidates whose reign was peaceful, long and prosperous enough to bring about the construction of such a massive building.4

One strong—albeit speculative—argument for claiming an even older, Old-Babylonian origin lies in the observation that King Hammurabi (r. 1792–1750 BCE) extensively financed the construction of ziggurats in other cities. It is therefore difficult to imagine that the monarch would have allowed the absence of a magnificent ziggurat in his own capital, while the settlements of his conquered dominions could boast of such a structure.5

History became Legend. Legend became Myth

As the vertical focal point of the city, the Etemenanki struck every visitor from far and wide with its sheer monumentality. Its description must have been on the tongue of every traveller and merchant eager to entertain his or her company. An echo of its visual impact can be found, for example, in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

“As the vertical focal point of the city, the Etemenanki struck every visitor from far and wide with its sheer monumentality.”

During the Neo-Babylonian period (626–539 BCE), many exiled Jews toiled in the fields of Babylonia, having been forcefully displaced there after Nebuchadnezzar II’s destruction of Jerusalem and the Kingdom of Judah in 587 BCE. This formed the historical backdrop against which several books of the Tanach, the Christian Old Testament, were written. Thus, references to Babylon’s wondrous monuments found their way into these texts. A spirit of animosity pervades these references—a logical consequence of the fact that many Jews dwelled in this foreign land completely against their will.

עַל נַהֲרוֹת, בָּבֶל–שָׁם יָשַׁבְנוּ, גַּם-בָּכִינוּ: בְּזָכְרֵנוּ, אֶת-צִיּוֹן

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.” -Psalm 137

The prevailing idea among the Judeans was that these buildings, for all their splendour and size, were unwarranted showpieces of pagan arrogance, bound to invoke God’s anger. The Etemenanki must have been one such structure, and it is generally agreed that this ziggurat became the inspiration for the famed Tower of Babel. The Tower of Babel is a parable from the Book of Genesis, intended to explain the enormous variety of languages in the world. The story goes that the people of Shinar (Lower Mesopotamia) decided to build a tower that reached the sky—an act that angered God to such an extent that he made the builders speak different languages. Thus, unable to communicate, the builders abandoned the project.

“these buildings, for all their splendour and size, were unwarranted showpieces of pagan arrogance, bound to invoke God’s anger.”

The Etemenanki not only left its mark on the Judeo-Christian tradition but also found its way into the writings of the Greek traveller-historian Herodotos (5th century BCE). This should not come as a surprise, as Herodotos is known to have travelled through the Achaemenid Empire, driven by a genuine curiosity about its cultures. Although he probably never set foot in the city, his journeys might have brought him into contact with those who did. His description of the city contains a section dedicated to the ziggurat:

“ἐν δὲ τῷ ἑτέρῳ Διὸς Βήλου ἱρὸν χαλκόπυλον, καὶ ἐς ἐμὲ ἔτι τοῦτο ἐόν, δύο σταδίων πάντῃ, ἐὸν τετράγωνον. [3] ἐν μέσῳ δὲ τοῦ ἱροῦ πύργος στερεὸς οἰκοδόμηται, σταδίου καὶ τὸ μῆκος καὶ τὸ εὖρος, καὶ ἐπὶ τούτῳ τῷ πύργῳ ἄλλος πύργος ἐπιβέβηκε, καὶ ἕτερος μάλα ἐπὶ τούτῳ, μέχρι οὗ ὀκτὼ πύργων. [4] ἀνάβασις δὲ ἐς αὐτοὺς ἔξωθεν κύκλῳ περὶ πάντας τοὺς πύργους ἔχουσα πεποίηται. μεσοῦντι δέ κου τῆς ἀναβάσιος ἐστὶ καταγωγή τε καὶ θῶκοι ἀμπαυστήριοι, ἐν τοῖσι κατίζοντες ἀμπαύονται οἱἀναβαίνοντες. [5] ἐν δὲ τῷ τελευταίῳ πύργῳ νηὸς ἔπεστι μέγας: ἐν δὲ τῷ νηῷ κλίνη μεγάλη κέεται εὖἐστρωμένη, καὶ οἱ τράπεζα παρακέεται χρυσέη. ἄγαλμα δὲ οὐκ ἔνι οὐδὲν αὐτόθι ἐνιδρυμένον, οὐδὲνύκτα οὐδεὶς ἐναυλίζεται ἀνθρώπων ὅτι μὴ γυνὴ μούνη τῶν ἐπιχωρίων, τὴν ἂν ὁ θεὸς ἕληται ἐκ πασέων, ὡς λέγουσι οἱ Χαλδαῖοι ἐόντες ἱρέες τούτου τοῦ θεοῦ.”6

“In the other (enclosure) arises the square-shaped sanctuary of Zeus Belos (Marduk) with a bronze gate, two stades long (384 meters) on each side, which still stands in my own time. In the middle of this sanctuary a tower was built of solid brick, a square stade in size, and atop of that tower stands another one, and another one upon that one, all the way up to an eight tower. On the exterior of all these towers a spiralling staircase was constructed. Somewhere along the middle of the staircase is a place with seats to rest, where those who climb the stairs can take a moment to catch their breath. Inside the last tower is a large sanctuary where there is a large bed, adorned with fancy coverings, with a golden table next to it. No statue has been placed there, however, and nobody spends the night there except for one native girl, whom the god supposedly chooses from all the women of the city, at least that is what the Chaldaean priests of that god claim”

These sparse and isolated descriptions of the tower in both Genesis and classical literature have added to the mystery surrounding it, instilling in generations a marked curiosity about the legendary megastructure. In medieval Europe, the Tower of Babel reappeared in miniature paintings time and again. This fascination in the European mind reached its climax through the hand of the brilliant Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Etemenanki formed the subject of one of his masterpieces, The Tower of Babel, dated 1563 and currently residing in Vienna. The biblical background story is visibly present through the sense of arrogance expressed in the titanic monumentality of the depicted tower. Herodotos also seems to have served as a source of information, as the ziggurat likewise contains eight levels. Bruegel’s access to information about the Etemenanki clearly stopped there, however, as the layout of the tower and the surrounding cityscape are evidently inspired by contemporary Flemish and ancient Roman architecture.

Rumours about the ancient tower reaching the celestial spheres not only inspired artists but also scholars who sought to determine the building’s historicity. One of the first genuine attempts to reconstruct its original appearance was undertaken by the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher in his Turris Babel, published in 1679. He based his work on descriptions from classical literature, and the result of his research was three possible reconstructions, each incorporating Herodotos’ idea of a spiralling staircase.

Modern Research

Fast forward to the 19th century, and we finally arrive in the epoch of modern archaeology. As the Middle East opened up to the European colonial powers in the wake of the faltering power of the Ottomans, so too did the archaeological sites become accessible to scholars determined to uncover the mysterious world of the Old Testament. One of their main questions was the veracity of famed wonders such as the Hanging Gardens and the Tower of Babylon. Already impressed by the capabilities of Mesopotamian architects through the discovery of giant ziggurats throughout the land, archaeologists turned their attention to uncovering the most famous of them all: the Etemenanki. Jules Oppert, leading the French expedition into Iraq in 1852, identified the ziggurat of Borsippa with Marduk’s tower, basing his assumption on the optimistic idea that the walls of ancient Babylon also enveloped nearby Borsippa and Kutha.

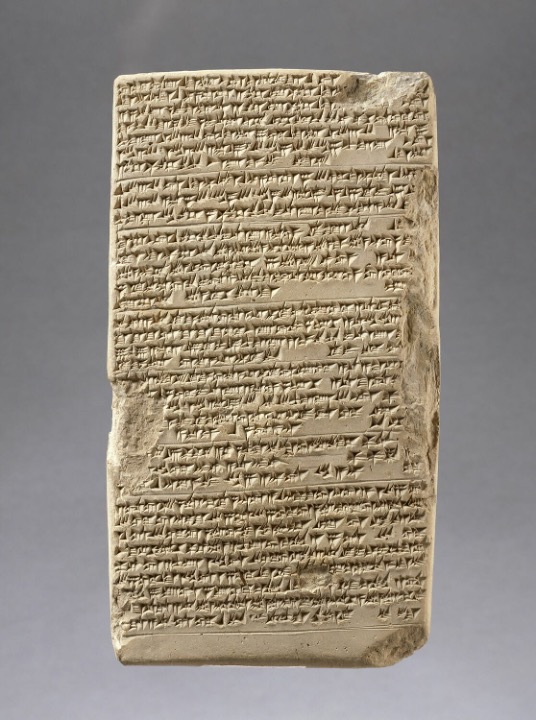

It was around the same time that one of the most influential sources in the research of the Etemenanki came to light: the so-called E-sangil tablet. It was found in the archives of the Eanna temple at Uruk and dates to the Seleukid period, i.e., 229 BCE, written by a certain Anu-Bēlšunu. We are dealing here with a copy of an original from the Neo-Babylonian period, with a second manuscript of the text later emerging from Babylon. George Smith made a quick translation of the tablet back in 1876. Later, in 1938, F.H. Weissbach published its first authoritative edition. The tablet describes a ziggurat of seven terraces instead of eight, with a square base measuring 91 × 91 meters and a height likewise measuring 91 meters (ten old nindan). The source also informs us that on top of the highest terrace stood a temple (nuḫar) dedicated to Marduk, containing several rooms that housed different gods and goddesses of the Babylonian pantheon. One room was called the “house of the bed,” which might refer to the ritual described above by Herodotos, although the Greek historiographer has often proven to be downright false in his passages comparing Babylonian culture to Egypt. Be that as it may, the tablet was formerly believed to be an actual description of the Etemenanki.

However, Andrew George has cast doubt on this view, claiming that the E-sangil tablet is rather a proposition of an ideal ziggurat.7 His main arguments lie in the tablet’s language, which is reminiscent of mathematical exercises, as well as the observation that the staircase of the Etemenanki is not steep enough to correspond to the height of the described ziggurat. Hansjörg Schmid, on the other hand, has suggested that it was an architectural plan for a reconstruction of Marduk’s ziggurat.8 In any case, George has demonstrated that the tablet should be used with caution.

The Discovery of the Remains

The quest for the Etemenanki gained momentum in 1901 when the Esagil temple complex was found under the ‘Amrān ibn ‘Alī hill. This indicated that the ziggurat could not be far away, as the surviving cuneiform tablets often refer to the Esagil in conjunction with the ziggurat. Weissbach identified the nearby Ṣaḥn Etemenanki as the site of the long-lost monument, but unfortunately, the archaeologists could not organise a dig due to the high groundwater level. This changed in 1913, when an exceptionally low level allowed Robert Koldewey to thoroughly investigate the mound. Soon enough, he indeed discovered the foundations of a massive monument. Babylon’s ziggurat had finally been brought to light from beneath the sands of time. Later, a second and final excavation of the site was organised in 1962 under the direction of H. Schmid.

“Babylon’s ziggurat had finally been brought to light from beneath the sands of time.”

Basing themselves on the excavation results and the E-sangil tablet – as long as its veracity wasn’t put in doubt (cf. supra) – a whole series of possible reconstructions emerged from the hands of various Assyriologists throughout the 20th century. To go through all of them goes beyond the scope of this paper, however.

Further Insights from the Archaeological Evidence

As the research progressed and more sources emerged, it became clear that the Etemenanki had often changed its appearance and went through different building phases. The Assyrian monarch Sennacherib claimed to have destroyed the ziggurat. His son and successor, Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BCE), began to rebuild it nine years later, along with the other temples and defences of Babylon. Letters have been unearthed in which references to the building’s progress can be found. That Esarhaddon was not able to complete the project can be deduced from Ashurbanipal’s claim to have also invested in rebuilding the Etemenanki. At the end of the 7th century, the first Neo-Babylonian ruler, Nabopolassar (r. 626–605 BCE), recorded how he found the tower in a dilapidated state (ullānū’a unnušat šuqūpat) and restored it to its former glory, with his son Nebuchadnezzar (r. 605–562 BCE) also claiming to have worked on the Etemenanki.9

Combining this written evidence with the archaeological finds, Schmid proposed an authoritative sequence of the different building phases.10 Three different bases were found at the Ṣaḥn Etemenanki: one measuring 65 meters, another 73 meters, and the youngest one 91 meters. He connected the oldest base with the ziggurat Sennacherib destroyed, the 73-meter base with Esarhaddon, and the largest structure with the Neo-Babylonian period. Andrew George has rightly pointed out, however, that this proposition—logical as it may seem—simply does not correspond to the written evidence. First of all, Esarhaddon already stated that the ziggurat measured 91 meters. Hansjörg Schmid, following Robert Koldewey’s suggestion, resolved this apparent issue by claiming that Esarhaddon measured the ziggurat using an older cubit standard of 40 cm instead of 50 cm.11 Marvin Powell, a specialist in Mesopotamian metrology, has found this very unlikely, however, as Esarhaddon did use the newer cubit standard of 50 cm in other documents. Furthermore, the oldest base of 65 meters is made purely of mudbrick (libittu), while Esarhaddon claimed to have used baked brick (agurru). The same applies to the 73-meter base, which is likewise solely made of mudbrick. This leaves us with no other conclusion than that the construction of the “latest” baked-brick version with a base of 91 meters had already begun under the Neo-Assyrian kings. This likewise proves, once again, that the ziggurat must be much older than the 1st millennium BCE.

This leaves us with the question of how the construction of the 91-meter ziggurat progressed. As already mentioned, Esarhaddon was not able to finish the building. We can infer from the written evidence that Ashurbanipal likewise could not bring the work to a conclusion, as he surely would have widely celebrated such an achievement. This could partly account for the dilapidated state in which Nabopolassar claims to have found the monument. In fact, as Andrew George points out, the unfinished state of the mantle would have exposed the core to the elements, which in turn would have significantly eroded the monument over the course of just a few decades.

This leaves us with the question of how the construction of the 91 meter ziggurat progressed. As already mentioned, Esarhaddon wasn’t able to finish the building. We can infer from the written evidence that Ashurbanipal likewise couldn’t bring the work to a conclusion, as he surely would have widely celebrated such an achievement.12 This could partly account for the dilapidated state in which Nabopolassar claims to have found the monument. In fact, as Andrew George points out, the unfinished state of the mantle would have exposed the core to the weather elements, which in turn would have significantly eroded the monument over the course of just a few decades.13

In any case, Nabopolassar initiated his building activity with pomp and circumstance, first carefully consulting the gods for the right measurements and purifying the premises through exorcists, before performing libation offerings and ritually placing the customary foundation deposit (temmēnu). An essential part of such foundation deposits were the famed inscribed cylinders, recording the act of reconstruction to demonstrate the king’s piety and worthiness to rule the country. Given the progress under Neo-Assyrian rule, it is more likely that Nabopolassar had the cylinder stored within the brickwork instead of the foundations, which by then would have been covered by a substantial mass of mudbrick and baked brick. The founder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire is said to have increased the height of the structure by another 15 meters.

“Andrew George suggests that the Etemenanki just fell short of reaching the 90-meter mark.”

His son and successor, Nebuchadnezzar II, continued his father’s efforts to embellish the capital with a ziggurat worthy of Neo-Babylonian might. The king informs us that he added another 15 meters, while also erecting the top-level shrine (kiṣṣu), which he adorned with a layer of exquisite blue-glazed bricks. It has been speculated that Babylon’s famed astrologers observed the stars atop this elevated sanctuary. There is, however, no compelling evidence that the work on the ziggurat was completed during the Neo-Babylonian dynasty. This might be reflected in the story of the Tower of Babel, which indeed describes an unfinished tower. Andrew George suggests that the Etemenanki just fell short of reaching the 90-meter mark. Nevertheless, based on these measurements, estimates of the total number of bricks used range between 32 and 45 million—a figure that conveys its incredible monumentality.14

The Decline of Babylon and the Etemenanki

When, in 539 BCE, the Neo-Babylonian Empire fell to the power of Cyrus the Great and Mesopotamia became a Persian satrapy, the cults of the native population were respected and continued by the central Achaemenid authorities. Thus, Marduk’s tower continued to be used in the following decades. Later Greek sources, however, report that King Xerxes finally had the ziggurat destroyed in retaliation for the Mesopotamian revolts against his rule in 484 and 482 BCE.15 Herodotos’ contemporary account, however, gives no hint that the Etemenanki had fallen into disuse in his day, leading scholars to entirely dismiss the later Greek narrative. Andrew George, however, has renewed interest in this tradition, claiming that some historical basis might be found for these stories.16 He has argued that the demolition of the southern staircase and damage to the mantle might be attributed to the period of the Achaemenids. As before, this would have exposed the mantle to the floodwaters of the Euphrates, which in turn would have slowly eroded the grandeur of the monument.

By the time Alexander the Great arrived in Babylon in 331 BCE, the ziggurat was once again in a ruinous state. As a sign of his goodwill, and to present himself to the local population as a legitimate ruler respectful of the native gods, the Macedonian king prepared to have the Etemenanki rebuilt. However, his untimely death in 323 BCE prevented him from carrying out these plans, and nothing more was achieved than the clearing of rubble down to the foundations. Afterwards, no major rebuilding project was undertaken, with locals gradually reclaiming the divine precinct to build their own houses from the Parthian period onwards. When archaeologists eventually stumbled upon the remains, they were disappointed to find that the foundations were all that remained of this once-mighty symbol of Babylonian power.

Olivier Goossens

Bibliography

- Boiy, T., Babylon: De Echte Stad en de Mythe, 2010, Leuven.

- Dalley, S., The City of Babylon: A History, c. 2000 BC – AD 116, 2021, Cambridge-New York.

- George, A., “The Tower of Babel: Archaeology, History and Cuneiform Texts”, Archiv für Orientforschung, Vol. 51, 2005/6, pp. 75-95.

- George, A., Babylonian Topographical Texts, 1992, Leuven.

- Powell, M., “Masse und Gewichte”, RLA, Vol. 7, 1989, pp. 457-517.

- Schmid, H., Der Tempelturm Etemenanki in Babylon, 1995, Mainz am Rhein.

- Vicari, J. & Bruschweiler, F., “Les ziggurats de Tchoga Zanbil (Dur-Untash) et de Babylone”, Le dessin d’architecture dans les sociétés antiques, 1984, Strasbourg, pp. 47-57.

- Von Soden, W., “Die babylonischen Königsinschriften 1157-612 v. Chr. und die Frage nach der Planungszeit und dem Baubeginn von Etemenanki”, ZA, Vol. 86, 1996, pp. 80-88.

- George 2005/2006, 84. ↩︎

- KAR 317; George 1992, 301-302. ↩︎

- Von Soden 1971, 258-259. ↩︎

- George 2005/2006, 87. ↩︎

- Schmid 1981. ↩︎

- Herodotos 1.181. ↩︎

- George 2005/2006, 76-79. ↩︎

- Schmid 1995,61-63. ↩︎

- Nbp 1 I 32-3. ↩︎

- Schmid 1981, 116-117; 1995, 69-74. ↩︎

- Powell 1989, 474. ↩︎

- George 2005/6, 81. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- Schmid 1995, 92; Vicari & Bruschweiler 1985, 56; Bielinski 1985, 61. ↩︎

- Arrianos and Strabon. ↩︎

- George 2005/2006, 91. ↩︎

Leave a comment