The immensity of the Mongol Empire makes it impossible for a single researcher to fully grasp all of its dimensions, whether political, cultural or religious. It is often pointed out that an independent study of this empire would require mastery of some fifteen languages, such is the diversity of sources and contexts. For this reason, it seemed appropriate to focus the analysis on a specific geographical area in order to offer an in-depth and nuanced perspective. This article does not therefore claim to cover the Mongol Empire (1206-1368) in its entirety, which at the beginning of the 14th century stretched from Eastern Europe to the Yellow Sea. Instead, it will focus on the case of the Ilkhanate of Persia (1256-1335) until Ghazan’s conversion to Sunni Islam in 1295, an event that profoundly transformed the religious and political balance. During this period, this area was home to a coexistence of Christians, Muslims, Buddhists and Jews under Mongol rule. Analysis of this context allows us to examine the concrete modalities of religious tolerance and to understand how an imperial power could reconcile religious diversity and political cohesion.

The Westward Expansion and the Genesis of the Ilkhanate

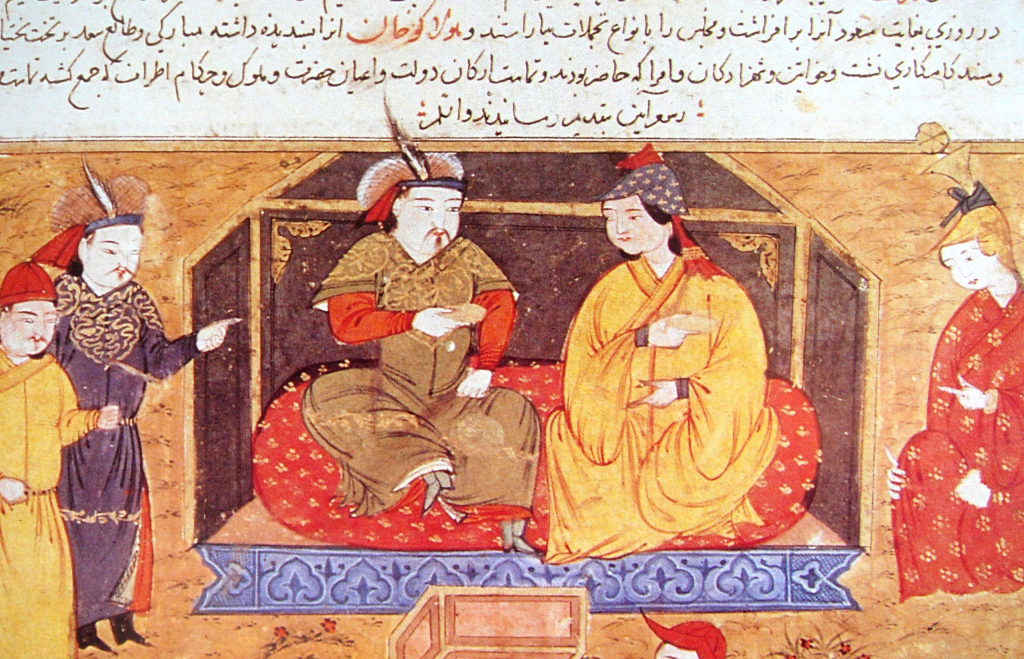

In 1251, the Great Khan Möngke entrusted Hülegü, his younger brother and grandson of Genghis Khan, with the mission of continuing the conquests begun by their illustrious ancestor in the direction of the Near East. The campaign began in 1256: the Mongol armies first set about pacifying eastern Iran, where they dismantled the fortresses of the Nizari Ismaili sect. They then subjugated the Lurs and Kurds, nomadic peoples of the western regions, before turning their attention to the territories under the Abbasid Caliphate, whose seat was in Baghdad.

One of the most significant episodes of this expedition was the capture of Baghdad in 1258. This event was not only a decisive military turning point, but also a profound upheaval in the political and religious balance of the Muslim world. The fall of the Abbasids marked the collapse of a prestigious centre of power, while ushering in a period of regional restructuring and the emergence of new power dynamics. Buoyed by his success, Hülegü continued his advance towards the Ayyubid territories, relying on a particularly effective military and administrative organisation that enabled the Mongols to consolidate their conquests.

However, this momentum was quickly interrupted. Upon Möngke’s death in 1259, Hülegü had to rush back to Mongolia to take part in preparations for the imperial succession. The campaign was therefore suspended. Nevertheless, a Mongol contingent remained in the conquered lands under the command of General Kitbouka. Kitbouka was defeated by the Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut on 3 September 1260, marking the first major Mongol setback and the last attempt at Mongol expansion in the Near East.

It was from these new conquests in the Middle East that the Ilkhanate of Persia drew its strength. It corresponded to the eastern part of the Mongol Empire and covered a vast region from Central Asia to the Levant. Its territory extended mainly over what we now call Iran in its broadest sense, but also included parts of eastern Turkey, the Caucasus, Iraq, and certain areas of Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Ilkhanate was founded by General Hülegü (✝ 1265) as part of the Mongol conquests aimed at extending imperial influence westward and securing trade routes and strategic hubs in the region. Under his rule, the Ilkhanate quickly became a major political and cultural centre, where different religious communities coexisted, providing fertile ground for studying the management of religious diversity within a conquering empire.

The Mongols’ Conception of Religion

“the Mongolian religion did not impose a universal faith, but affirmed the cosmic and political mission of the sovereign”

At the time of their expansion in the 13th century, the Mongols were not characterised by adherence to a single, dogmatic or proselytising religion. Their conception of the sacred was rooted in a set of shamanic and animistic beliefs inherited from the Altai steppes, where the cult of the eternal sky (Tengri) and protective spirits predominated. This religious system, often referred to as Tengrism, emphasised harmony between the human order and natural forces, while conferring a transcendent dimension on political sovereignty.

Thus, the legitimacy of power was based on a heavenly investiture: Genghis Khan presented himself as the one who ruled ‘by the will of the Eternal Sky’. From this perspective, the Mongolian religion did not impose a universal faith, but affirmed the cosmic and political mission of the sovereign. As Dorothea Krawulsky points out, this fundamental distinction between religion and political domination is a striking feature of Mongolian thought:

“The Mongols also brought this idea with them, but contrary to Islam, which claims world domination for the religion, the Mongols claimed world domination for Cingiz Khan and his descendants.”1

In other words, whereas Islam aspired to religious hegemony based on converting peoples, the Mongols claimed universal imperial domination legitimised by Heaven, regardless of religious affiliation. This fundamentally pragmatic and inclusive conception explains their policy of religious tolerance towards conquered populations.

However, this same imperial vision quickly came into conflict with the Latin West. The Christians of Europe, while sometimes perceiving the Mongols as possible allies against the Muslim Mamluks, remained wary of an empire that also claimed a universal vocation. In medieval Western ideology, the Christian world, under the authority of the Pope and Christian kings, also saw itself as the bearer of a universal order willed by God. Consequently, the prospect of a genuine alliance between the Latins of the West and the Mongols was hampered by a conflict of legitimacy: two empires faced each other, each claiming universal sovereignty based on a transcendent principle—Heaven for the Mongols, the Christian God for the West.2

A Pragmatic Syncretism

“this policy did not mean true equality between faiths. The Mongols favoured the religions and religious authorities that showed them loyalty or support”

During their expansion into the Near East, the Mongols adopted a religious policy based on a principle of pragmatic tolerance. True to their political ideology derived from Tengrism, they generally allowed conquered populations to retain their religious practices and spiritual institutions, provided that these did not challenge the authority of the Khan or the stability of the imperial order. This approach was less an ideal of religious coexistence than a strategy of government: in such a vast and heterogeneous empire, religious flexibility was an attractive tool for integration.

Of course, this policy did not mean true equality between faiths. The Mongols favoured the religions and religious authorities that showed them loyalty or support, while marginalising those that could embody political resistance, such as the Sunni Muslims. However, if this political veil were lifted, those who were best able to serve the authorities in a given territory were obviously those found in the highest echelons of the state. For example, Muslim elites continued to dominate culture due to their sheer numbers and thus enjoyed better representation in institutions as long as they supported the Khan.

Evidently, the attitude of the Mongol Khans reflected an instrumental conception of religion: the various faiths were perceived as spiritual forces that could be harnessed in the service of imperial power. They consulted representatives of different confessions—Buddhist monks, imams, Nestorian priests, and others—and frequently granted fiscal privileges to religious institutions. Notably, religious establishments such as Sufi khanqahs, Buddhist monasteries, Christian convents, and synagogues were often exempted from the land tax (kharaj) on their estates or gardens, which were regarded as spaces consecrated to worship. Similarly, certain Muslim communities enjoyed the darkhan status, which exempted religious figures from taxation and military service.

In sum, the Mongols’ religious policy in the Near East stemmed above all from political pragmatism rather than genuine spiritual tolerance. By allowing the various communities to maintain their respective faiths while demanding their loyalty, the Khans transformed religion into an instrument of stability and a means of legitimising imperial authority. This approach also contributed to the relatively favourable perception of the Mongols in the region: they were seen at times as pagan invaders, at others as equitable rulers promoting interconfessional coexistence.

The Latin Perception of Mongol Religion

However, this conception of religion did not appeal to everyone. The Latin missionaries provide us with a revealing testimony of how Mongol religiosity was perceived in the West.

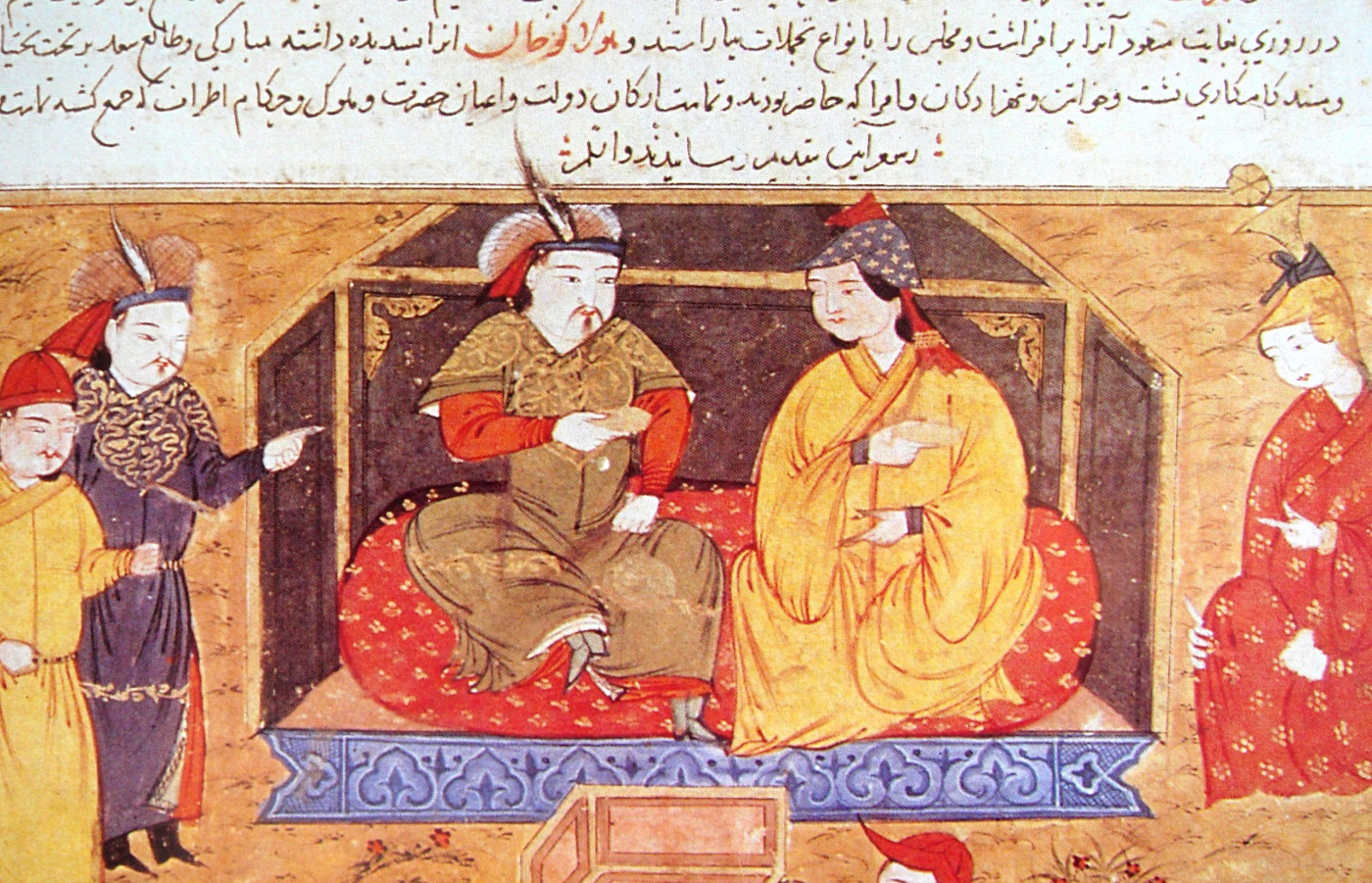

During his stay at the Mongol court in the mid-thirteenth century, the Franciscan envoy sent by Saint Louis, William of Rubruck, had the opportunity to engage in a theological debate with the general Kitbuqa, an influential figure within Mongol authority. In his account, Rubruck is particularly severe towards the Mongol Nestorian priests, whom he accuses of immorality and misconduct, describing them as “usurers, drunkards, and polygamists (…) who eat meat on Fridays and feast on that day like the Muslims! And like the Muslims, they wash their lower limbs before entering the church!”.3 He also notes that Karakorum, the imperial capital, housed “two mosques and twelve pagodas or other idolatrous temples,” a vivid testimony to the religious plurality that characterised the Mongol Empire.

To these reproaches, Kitbuqa responded calmly and precisely, emphasising the organised coexistence of different faiths within the imperial administration: “That is correct, but I must clarify three things: our Muslim clergy are Shi‘a, thus hostile to the Caliphate of Baghdad; although our Great Khan Möngke is a shamanist, one of his wives is Nestorian, as was his mother (…) finally, the Nestorian priests are the first to bless the Great Khan’s cup, followed by the Muslim imams and the Buddhist or Taoist monks. This hierarchy underscores the importance of my Nestorian brethren.”4

This dialogue powerfully illustrates the institutionalised religious diversity within the Mongol Empire. Far from seeking to impose uniformity of belief, the Mongols acknowledged and ranked the various faiths according to their political usefulness and their proximity to power. Such a conception of religion was grounded in equilibrium and imperial legitimacy rather than in doctrinal exclusivity, as was the case in medieval Europe.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the example of the Ilkhanate of Persia prior to Ghazan’s conversion illustrates the capacity of an imperial power to navigate a context of profound religious diversity without seeking to impose doctrinal uniformity. This pragmatic coexistence, regulated by administrative norms and a political hierarchy, reveals that Mongol tolerance was not an abstract ideal but a strategic component of governance. Beyond military and political considerations, it also fostered a sphere of sociability and cultural exchange among distinct communities, contributing to the economic, intellectual, and artistic vitality of the region. Finally, the study of this case highlights the importance of considering local and imperial dynamics in all their complexity, and invites us to move beyond the simplistic judgements inherited from Western narratives, in order to appreciate the richness and ingenuity of the modes of religious coexistence that characterised medieval Asia.

One may encapsulate the Mongol conception of religiosity through an image: it is as if the palm of a hand represents the single foundation embodied by Chinggis Khan, while each of the fingers symbolises a distinct religion. This metaphor illustrates how the Mongol imperial power functioned as a central anchoring point — a kind of matrix — ensuring order and legitimacy, while religious diversity flourished around it without threatening political cohesion. Thus, all faiths found their place under the authority of the Khan, each fulfilling a specific role within the equilibrium of the imperial system.

Contemporary scholarship has done much to refine our understanding of religious tolerance under the Mongols. Distinguished historians such as Thomas Allsen, Michal Biran, and Peter Jackson have demonstrated that this coexistence was not the product of a humanistic ideal, but rather the outcome of a complex political strategy grounded in pragmatism and the maintenance of imperial order. However, the historiographical debate remains lively: some scholars emphasise the genuine and enduring character of this tolerance, while others interpret it primarily as the instrumentalisation of religion in the service of legitimacy and the consolidation of power. From this perspective, the concurrent use of Persian, Chinese, and Latin sources proves essential in overcoming the biases inherent in each tradition and in restoring a balanced understanding of Mongol religious practice.

Ethan Zelko-Yılmaz

Ethan Zelko-Yilmaz holds a double bachelor’s degree in history and political science from ICES. He also holds a certificate in theology from the same institution. He is pursuing a master’s degree in history at EPHE-PSL on the perception of the Mongols by the populations of the Eastern Middle East in the 13th century.

Bibliography:

- Timothy May & Michael Hope, ‘The Mongol World‘, Taylor & Francis, Routledge, Londres, p. 1068, 2024.

- Dorothea Krawulsky, ‘The Mongol Īlkhāns and their Vizier Rashīd al-Dīn’, Peter Lang, Francfort, p. 156, 2011.

- Matthew J. Dundon, ‘Bar Hebraeus Chronography‘, Hohhot, p. 151, 2021. (memoir rendering).

- Paul Anselin, Kitbouka, ‘Le Croisé mongol‘, Jean Picollec, Paris, p. 329, 2011.

- Michal Biran & Hodong Kim, ‘The Mongol Empire‘, vol 1, History, The Cambridge History of, Cambridge, p. 930, 2023.

- Baabar, Almanac, ‘History of Mongolia‘, Nepko, p. 357, 2017.

- Reuven Amitai, ‘The Mongols in the Islamic Lands, Studies in the History of the Ilkhanate‘, Variorum collected Studies series, Ashgate, Burlington, p. 390, 2007.

- ‘Histoire secrète des Mongols, Chronique mongole du XIIIe siècle‘, trad. Marie-Dominique Even & Rodica Pop, préface Roberte Nicole Hamayon, Connaissance de l’Orient, col UNESCO d’oeuvres représentatives, Gallimard, p. 349, 1994.

- Nathan Fancy & Monica H. Green, ‘Plague and Fall of Baghdad (1258)‘, Cambridge University Press, pp. 157-177, 2021.

- Mark Cartwright, ‘Ilkhanate Perse‘, trad. Bebeth Étiève-Cartwright, World History Encyclopedia, p.7, 2019.

- Dorothea Krawulsky, ‘The Mongol Īlkhāns and their Vizier Rashīd al-Dīn’, Peter Lang, Francfort, p. 156, 2011. p. 62. ↩︎

- Paul Anselin, ‘Kitbouka, Le Croisé mongol, Jean Picollec‘, Paris, p. 329, 2011, p. 231, 241-248. ↩︎

- Paul Anselin, ‘Kitbouka, Le Croisé mongol, Jean Picollec‘, Paris, p. 329, 2011, p. 246 ↩︎

- Paul Anselin suite p. 246. ↩︎

Leave a comment