History is filled with stories of last stands, of small forces engaging an enemy many times their strength for one reason or another. The siege of Antioch (1097-1098) during the First Crusade, the lone Norwegian warrior at Stanford Bridge (1066) … all of these have been etched into humanity’s shared memory. Arguably the most famous last stand, however, took place at Thermopylae where, in 480 BCE, a force of seven thousand Greeks faced off against Xerxes’ army for three days before being overwhelmed. This battle has become an enduring symbol in the West, as it was regarded as a pivotal moment in the development of the Hellenic and future Western cultural identity. Although it is most certainly a momentous event in history, a very similar military encounter would occur over a century later. This battle contains all of the elements that make last stands such compelling stories. A small force faced off against a much large opponent, desperate to buy the time needed to save their world from destruction, with displays of incredible bravery as well as ingenuity on both sides. And yet, even with all these elements, this battle is rarely remembered alongside the other great last stands of history. This article will go through this story and aims to give it the attention it deserves.

Setting the Scene

When Darius III became the King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire in 336 BCE, he had assumed control of one of the mightiest empires humanity has ever seen. Its borders stretched from the Aegean sea and Libya in the west to the Eurasian Steppe and India to the east. His realm was arguably the wealthiest of its time and he controlled vast and powerful armies and fleets. To make his position even more favourable, Philip of Macedon, who had united Greece under his rule and intended to march on Persia, had fallen to an assassin’s blade, sowing chaos in the Macedonian and Greek world. The Persian position as the dominant power in the known world, it seemed, was unassailable.

It was this very situation that would make the series of events that would follow all the more remarkable. Philip’s son, Alexander, took the throne as Alexander III, and, after having violently regained control of both Greece as well as the lands to his north, took his army and attacked the Persian Empire. His first victory was secured at the river Granicus where, in May 334 BCE, he defeated the larger provincial armies of the Persian Satraps, or governors. After having taken the coastal cities as well as the provincial capitals in central Anatolia, Alexander faced Darius III at the battle of Issus, winning yet another victory and forcing Darius to flee the field in order to regroup and organise a counter-attack. In a blow to his prestige, Darius was even forced to abandon his family, whom Alexander took into his care. After having subdued Egypt, Alexander faced Darius in battle one last time in 331 BCE, on the plains of Gaugamela in modern Iraq. Darius had amassed troops from across his vast empire for this battle, and had even had his troops flatten the field and remove any vegetation or rocks in order for his cavalry and chariots to operate more easily. Despite all these preparations, his superior numbers and some early successes in the battle, Alexander still emerged triumphant, inflicting enormous casualties and forcing Darius to flee the field again, this time to the East of his empire in order to organise another attack.

With the defeat at Gaugamela, Alexander could now easily take control of Babylon, the administrative heart of the empire. He would crown himself King of Asia and, having rested his troops, make his way towards Parsa, the homeland of the Persians in the modern Iranian province of Fars.

Alexander’s Path

Darius had travelled to Ecbatana, one of the empire’s capitals, to work on gathering an army from his remaining eastern provinces, a process that would take time. With his securing of Babylon, Alexander now intended to seize control of the other capitals of the Empire and to capture Darius in order to cement his right to rule.

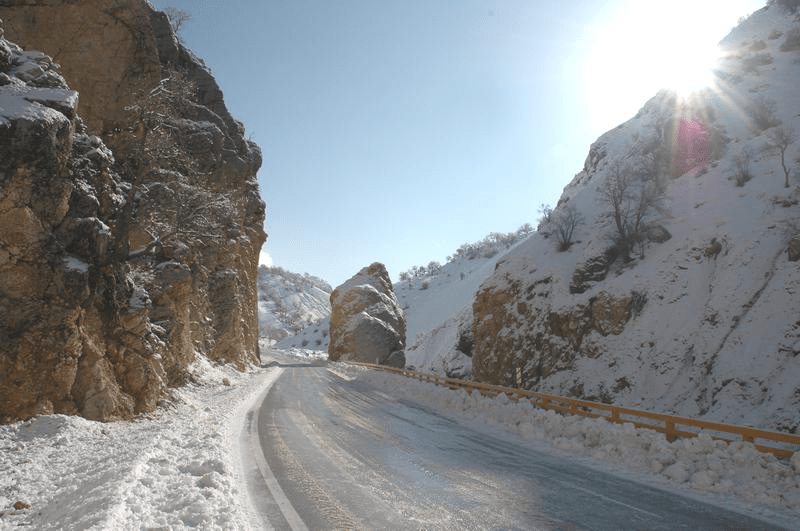

Alexander gathered his troops along the famous Royal Road. This road, commissioned by Darius the Great almost two centuries prior, connected the satrapies of Asia Minor to the empire’s political centre. He quickly reached and occupied Susa, one of the Achaemenids’ great capitals, using the massive wealth found within to pay his troops as well as help support his forces back in Macedon. Instead of wintering in the city, Alexander decided to press on through the Zagros mountains in order to quickly reach Parsa, where he subdued the bellicose Uxian tribe along the way. Before entering Parsa proper, Alexander split his army, one portion under Parmenion taking an easier northern route while he would lead his force, numbering around 14-20 thousand troops, on a forced march through the mountain passes in order to reach Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the empire. It was in these passes, known as the Persian Gate, that Aryabarza (whom the Greeks would refer to as Ariobarzanes), Satrap of Parsa, was waiting for him.

The Persian Situation

“It now fell to Aryabarza to face Alexander and buy the king as much time as he could.”

Under most circumstances, being named governor of the heartland of the empire, location of cities such as Persepolis and treasures like the tomb of Cyrus the Great, would have been an immense honour. This position was, unfortunately, a most unenviable one for Aryabarza, the newly appointed Satrap. His role had never existed before, having been created as an emergency measure while Darius was in Media trying to gather another army. It now fell to Aryabarza to face Alexander and buy the king as much time as he could.

With regard to the forces at Aryabarza’s disposal, the situation was far from ideal. Ancient sources such as Arrian, Curtius Rufus, and Diodorus describe his defense of the Persian Gate but provide little concrete information when it comes to the overall numbers of the Persian force. The Persian military had already suffered severe losses at the Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela, with ancient estimates of the dead running into the tens of thousands, greatly reducing the manpower available for Parsa’s defense. At the same time, Darius III was attempting to raise a fresh army further east, further limiting Aryabarza’s available recruitment pool. Modern historians therefore suggest that Aryabarza could only have fielded a relatively small force, perhaps as few as 700–1,200 men, or at most a few thousand, composed of local levies, irregulars, and any remaining professional soldiers.

Unfortunately, while we know that Alexander was bringing his phalangites, the pike wielding front line infantry of the Macedonians, as well as cavalry and Agrianian skirmishers, very little is known about what kind of troops Aryabarza had access to but certain assumptions can be made. He would most likely have had access to provincial levies from Parsa itself, who would have fought both as spearmen and archers. He may have made use of local irregulars to fight as skirmishers, while some modern historians posit that he may have recruited professional infantry that had survived the battles of Issus and Gaugamela, who would have also acted as both close quarter fighters and archers. Some sources have also stated that Aryabarza had a small retinue of cavalry accompany him into battle, which included his sister Youtab, but they would have been far too few in battle to make a major difference.

“Aryabarza did as the Greeks did at Thermopylae and selected a location that would maximise his troops’ abilities”

To mitigate this issue, Aryabarza did as the Greeks did at Thermopylae and selected a location that would maximise his troops’ abilities while turning his enemy’s numerical superiority into a detriment. He chose a position near the modern village of Cheshmeh Chenar, where the valley curves and narrows considerably, creating a natural choke point which was only a few meters wide at certain points. The Persians built a makeshift wall to block off the pass and hid the majority of their troops in the slopes surrounding the choke point, waiting for their enemy to arrive.

The Battle Begins

Alexander would have seen a wide valley in front of him as he approached, easily allowing his army to march through and towards his target. It is unknown why but he had decided against sending any scouts into the pass, making his army easy prey for what was to come.

As the army advanced further, the slopes of the pass closed in, forcing the troops to march in a much tighter formation and at a much slower pace. As the vanguard troops of Alexander’s army rounded the bend in the pass, they came upon the wall that the Persians had built and came to a halt, falling directly into the Persians’ trap. Archers and skirmishers emerged from their hiding places on the slope and showered the bewildered Macedonian troops with javelins, arrows and stones. What made the Macedonian troops’ situation even worse was that the rest of the army was still advancing into the pass, making a retreat impossible. The Macedonians started taking heavy casualties and, seeing how poorly his troops were faring, Alexander ordered his troops to retreat from the pass, although the Persians would make them bleed with further ranged attacks as they moved away from the pass.

Alexander the Great was held at bay by the Persian forces under Aryabarza for an entire month. This turn of events would have surely given Aryabarza hope, as any amount of time delaying Alexander at the pass was more time for Darius to build an army to wipe the invaders out, which would have changed the course of history. There was even the chance that Alexander could die which, given how quickly his generals turned on each other after he perished, may have totally unravelled the Macedonian war effort, yet again massively changing the course of history. Unfortunately for the defenders, and for the Persian Empire as a whole, Alexander’s fortunes were to change in his favour.

A New Path

As Alexander and his commanders pondered over how to storm Aryabarza’s position, his luck would finally turn. Some sources state that it was Persian prisoners while others, in a tale reminiscent of the Thermopylae one and a half century earlier, say that it was a local shepherd who revealed a treacherous path that led up the mountain and around the Persian position. He sent a portion of his force under Ptolemy and Perdicas along the pass, where they set up camp and waited for the signal to attack the Persian rear.

The Final Clash

Once the sun rose, Alexander attacked the Persian position with the elite contingents of his army, pinning the defenders in place. The force under Ptolemy then descended from the mountain and appeared behind the Persian position, attacking the Persian rear.

Even though their position had collapsed, the Persian soldiers fought ferociously, displaying incredible bravery in the face of certain death. One source, Curtius, wrote that, even after they lost their weapons, the Persian soldiers furiously threw themselves onto their Macedonian opponents and pull them to the ground, sometimes killing them with their own weapons before being slain in turn.

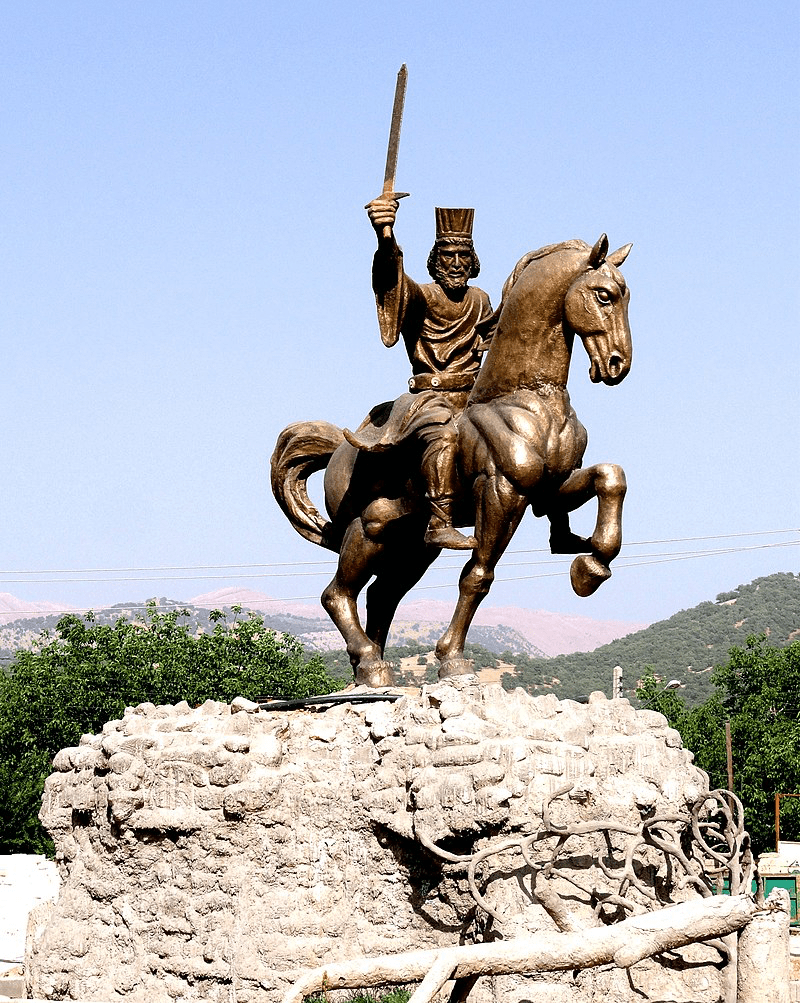

Aryabarza’s final fate has been recounted in several ways, but all end in the same manner. Some sources say that he was forced to surrender and was then executed by Alexander as punishment for the difficulty he had caused him. Others say that, seeing the battle was lost, he and his sister led the cavalry into a suicidal charge, selling their lives for the empire’s cause. The third version of events, however, states that Aryabarza escaped from the battle with his retinue and retreated to Persepolis to organise a defence of the palace, only to find the gates barred and the overseer of the palace already intent on surrendering to Alexander, who was close behind. With no other option, Aryabarza would, just as in the second version, charge at the Macedonians and fought them to the last.

The Aftermath

Although the Battle of the Persian Gate does not command the same fame as Issus or Gaugamela, it was one of the most politically and symbolically significant clashes of Alexander’s campaign. Aryabarza’s defeat removed the last organised resistance in Parsa and opened the road to Persepolis, the ceremonial heart of the Achaemenid Empire. Its capture and subsequent destruction dealt a devastating blow to Persian culture and identity, an event remembered in later Iranian tradition as a moment of profound trauma, with Alexander cast as a near-demonic figure. Politically, the fall of Persepolis marked the end of Persian resistance in the imperial heartland and forced Darius III to continue his flight eastward, where his authority quickly unravelled and he was ultimately betrayed and killed by his own nobles. His death ended any unified imperial resistance and left Alexander free to press his conquests deeper into Asia.

In contrast to the political collapse that followed his defeat, Aryabarza’s stand at the Persian Gate lived on in cultural memory. Ancient Greek and Roman sources portray him as a determined satrap who chose to fight against overwhelming odds, and later Iranian tradition would elevate him further, transforming him into a symbol of patriotic resistance. His desperate defence of the pass, just as with Leonidas at Thermopylae, has earned him a place in Persian folklore as a martyr-like figure who sacrificed himself for his homeland. In this way, Aryabarza embodies both the bravery of the Persian troops who resisted Alexander and the enduring theme of defiance in the face of conquest that have made last stands like his such enduring motifs in our collective story.

Milo Reddaway

Further Reading

- Arabzadeh Sarbanani, M., 2024. From Thermopylae to the Persian Gates: A New Look into Ariobarzanes’ Identity and Political Status. Persica Antiqua, 4(6), pp.33-44.

- Heckel, W., 1980. Alexander at the Persian gates. Athenaeum, 58, p.168.

- Konijnendijk, R., 2012. ‘Neither the Less Valorous nor the Weaker’: Persian Military Might and the Battle of Plataia. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, pp.1-17.

- Rop, J., 2025. The Persian Way of War: Infantry Tactics in the Achaemenid Empire. IRANIAN EMPIRES, p.187.

Leave a comment