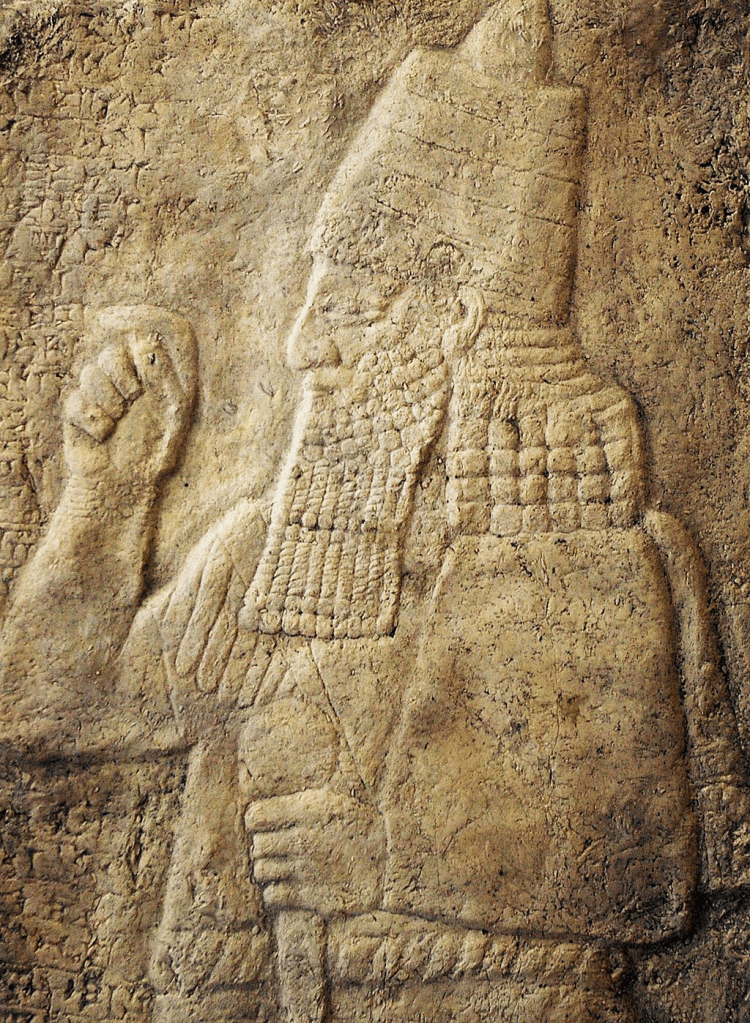

One of the British Museum’s biggest attractions are the numerous mural reliefs drawn from the Neo-Assyrian capital of Nineveh. Situated in hall XXXVI, a 27 meter long relief tells us in great – and sometimes shocking – detail the story of a siege. The continuous scene depicts the assault, scaling of the walls through ladders and a ramp, the gruelling execution of the city’s leaders and the deportation of its inhabitants. Through the accompanying inscriptions, we were able to identify the settlement as the Judean stronghold of Lachish, the Kingdom of Judah’s ‘second city’, toppled by King Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BCE) in 701 BCE. Although strangely not mentioned in his royal inscriptions, the king must have been particularly proud of this achievement, as the sculptural masterpiece adorned one of the central rooms of his gigantic new “Southwest” palace of Nineveh, uncovered between 1845 and 1847 by a then still young Austen Henry Layard.

The reliefs are best understood against the historical background of Sennacherib’s decision to move the Assyrian capital from the short-lived Dur-Sharrukin closer to the banks of the Tigris at Nineveh. Through the size of his new palace, which was the biggest the world had seen thus far, and its exquisite reliefs, the king wanted to impress and perhaps intimidate his visitors with the wealth and power of his empire. Depicting a successful siege showcasing the Assyrian army’s lethal efficiency in punishing the state’s enemies must have certainly done the trick. However, let’s briefly look past the propaganda of Nineveh, and try to have a better understanding of the historical event depicted. In fact, as we shall see briefly, the siege of Lachish is perhaps one of the best documented battles from Ancient Near Eastern history, with -besides the relief sculptures- written sources from both sides and archaeological evidence shedding light on the event.

The Source Material

The Siege of Lachish is extremely interesting for the variety of the source material available. Besides the figurative evidence from the wall reliefs, Sennacherib had his version of the course of events described in his Annals. Likewise, the Bible informs us of the Assyrian campaign of 701 BCE in Isaiah 36 and 37, 2 Kings 18:17 and 2 Chronicles 32:9, understandably so, given the Hebraic stakes in the events. Another description comes from a rather unexpected corner, as Herodotos provides us with a 5th century BCE-take on Sennacherib’s expedition in the Levant. Finally, and more importantly, the site of Tell ed-Duweir, identified as ancient Lachish, has yielded many intriguing vestiges of the ancient siege.

Historical Background: Sennacherib’s “Third Campaign”

“As had happened often before, the death of the king sparked a series of revolts by the various vassals and provinces in an attempt to throw off the burdensome Assyrian yoke.”

Sennacherib succeeded his father, Sargon II, in 705 BCE, who had fallen while campaigning against the Anatolian kingdom of Tabal. Already before his investiture as king, Sennacherib had proven himself to be an able diplomat and administrator. The precarious situation in the empire upon his father’s died, however, demanded of him to put a on a different mask, i.e. that of a military leader. As had happened often before, the death of the king sparked a series of revolts by the various vassals and provinces in an attempt to throw off the burdensome Assyrian yoke. Sennacherib did not tarry to launch various military expeditions to keep his father’s empire together. His first destination was the ever troublesome country of Babylonia, plagued by continuous Aramaean and Chaldean incursions, before leading his troops to the Zagros Mountain range during his second campaign.

“before being able to put the Hebraic monarch back in line, he first had to wrestle himself through numerous throngs of Levantine troublemakers who awaited him along the road to Jerusalem.”

In 701 BCE, he turned westward to take care of the precarious situation in the Levant, where the intricate network of pro-Assyrian vasal states and dependencies was in danger of falling apart. Several states ousted their pro-Assyrian rulers, ended paying tribute and rose up in arms. Although it is difficult to determine the exact relationship between these various rebellious factions, it is reasonable to assume that Hezekiah, the King of Judah, played a key role in the uprising as one of the most powerful rulers in the region. However, before being able to put the Hebraic monarch back in line, he first had to wrestle himself through numerous throngs of Levantine troublemakers who awaited him along the road to Jerusalem.

Sennacherib’s first stop was the Phoenician coastline, where king Luli had ceased paying homage to Assyria and expanded his power without the king’s consent. As soon as the Assyrian forces marched into the coastal region via the crossing at Carchemish, Luli sailed to Cyprus. Deprecated as a despicable act of cowardice in Assyrian propaganda, the Phoenician monarch’s journey across the Levantine Sea was rather a calculated tactical retreat. Luli thought it better to direct his resistance from a safe distance at one of his Cypriote colonies. The war did not fare well for him though, as Sidon and Akko fell into Sennacherib’s hands. Thus, Luli’s power on the mainland was henceforth restricted to the impregnable fortress of Tyre. The Assyrian king contented himself with the results, put Phoenicia under the control of a puppet king, Ittobaal, and descended toward the territory of the Philistine city-states.

While Gaza and Ashdod stayed loyal to their overlord, Ashkelon and Ekron tried to free themselves from the Assyrian shackles. Ashkelon was dealt with quickly, but things got complicated off the gates of Ekron, as the Ekronites had called upon the Egyptians for aid. Egypt, Mesopotamia’s eternal rival, was then governed by the Kushite kings of the 25th dynasty. Detecting an opportunity to expand their influence into the Levant, the Kushites answered the call. The Assyrians and Egyptians met at Eltekeh, a place between Ekron and Gibbethon. The Assyrians claimed a resounding victory, Herodotos the opposite and the Bible remains silent on the battle’s outcome. It is reasonable to assume, however, that Sennacherib did indeed succeed in driving away the Egyptian soldiers, as he subsequently laid siege to and conquered Ekron. He slaughtered the ring leaders of the rebellion and restored his protégé, Padi, to the throne. With the last pocket of Philistine resistance suppressed, Sennacherib was finally able to commit fully to fighting the Kingdom of Judah.

Fighting Judah

Sennacherib’s fight against Hezekiah was swift and ruthless. His Annals claim that he managed to capture 46 cities in Judah before heading to Jerusalem, a feat confirmed by the Bible. Among these settlements was Lachish, Judah’s second city, some 40 kilometres southwest of the kingdom’s capital. Situated along the south bank of the synonymous Lachish River, this ancient settlement, whose history dates back to the Neolithic, arose atop a solitary hill with a good view of the surrounding countryside. With strong walls augmenting its excellent natural defences, Lachish proved to be a tough nut to crack. However, the Assyrian army had a few tricks up its sleeve.

“With strong walls augmenting its excellent natural defences, Lachish proved to be a tough nut to crack.”

Thanks to the abovementioned palace reliefs and the archaeological finds at the site of Lachish, i.e. Tell ed-Duweir, we have an unprecedented rich variety of source material at our disposal, which offer us a unique look into how the Assyrians toppled this stronghold. Finds such as hundreds of arrowheads act as silent witnesses to these troubled days in the city’s history. The most extraordinary find, however, was the huge 80-meter long artificial ramp built by the Assyrians against the southwestern portion of the city’s walls, a stratagem also depicted in the reliefs from Nineveh. By constructing a causeway against the Judahite defences, the Assyrians thus countered the settlement’s height advantage. Thanks to Professor Yosef Garfinkel’s recent excavations, we now have a better view of how the Assyrians built their ramp.

Firstly, the location of the ramp was carefully chosen at the southwestern corner of Lachish’s wall, sharply bent inwards at a very tight angle. This meant that only a limited portion of the wall had the oncoming Assyrians within its field of fire, meaning only a limited number of defenders could hurl stones and arrows at the attackers. To further limit the danger of projectiles, a shield wall was probably constantly put up by the soldiers behind which the workers could operate.

This begs the question: how was it even possible for the Assyrians to construct such an enormous structure? Luckily, Yosef Garfinkel has provided us with the necessary answers. His dig at Tell ed-Duweir has uncovered a cliff-like area only 120 meters south of Lachish, whence the Assyrians could have gathered a remarkable number of stones. Given the average weight of 6.5 kg (14.3 pounds) of the boulders, it would have taken about 3 million stones, i.e. 20.000 tons, to build the structure. Based on this evidence, Garfinkel estimated that its construction would have lasted three weeks, provided four teams of men passed on the boulders in a long row, non-stop, day and night, at a rate of about 160,000 stones a day.

Once finished, the surface of the ramp was flattened by smearing it with mud before laying out a platform of wooden logs. Thus, it became possible for the Assyrians to bear down on the enemy, previously tucked away safely behind their walls, with their formidable siege machines, as depicted in the reliefs.

Although it is difficult to discern whether the rampart was the decisive factor in the eventual defeat of Lachish, it must surely have contributed greatly to the city’s downfall. Sennacherib afterwards continued his march and finally arrived before the gates of Jerusalem. However, the Assyrian war machine proved to be unable to capture the kingdom’s heavily fortified capital. Nevertheless, King Hezekiah relented and signed a peace treaty with Sennacherib, acknowledging Assyrian hegemony over the Levant in return for keeping his throne. The peace settlement was extremely costly for the Hebraic king: large parts of Judah’s territory were distributed among Ekron, Ashdod and Gaza, many families were deported to Mesopotamia, and the Judahite king henceforth had to pay tribute to Ashur. Sennacherib’s campaign can therefore be considered a success, as he left a strong system of Assyrian vassals in his wake, after having driven out his Egyptian rival. Judah would never again defy Assyrian rule. Thus, Sennacherib laid the groundwork for Assyria’s next great imperial achievement: the conquest of Egypt in 673 BCE, but this is a story for another day.

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of Lachish returned to their homes and repaired their fortifications, destroying part of the Assyrian ramp. Amid the ruins of their past, the indefatigable people of the city were able to build up a future once more, with signs of life appearing in the archaeological record up until the day and age of Alexander the Great.

Olivier Goossens

Bibliography

- Collins, P., Assyrian Palace Sculptures, 2019, London.

- Eames, C., “How Sennacherib’s Assyrians ‘Poured’ Their Way into Hezekiah’s Lachish”. Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. Consulted through. https://armstronginstitute.org/4-how-sennacheribs-assyrians-poured-their-way-into-hezekiahs-lachish.

- Elayi, J., L’empire assyrien, 2024 (2021), Paris.

- Frahm, E., Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Empire, 2023, London.

- Steinmeyer, N., “Sennacherib’s Siege of Lachish”. Biblical Archaeology Society. Consulted through https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-sites-places/biblical-archaeology-places/sennacheribs-siege-of-lachish/.

Leave a comment