“Beauty surrounds us, but usually we need to be walking in a garden to know it”

-Rumi

Gardens have taken on a myriad of forms and functions over the millennia, from areas of contemplation and wonder to the production of food. And yet, it would be in Iran, under the rule of the Great Kings, where gardens would become true expressions of artistry, ideology and a search for the sublime. The idea of the garden as a place of wonder, beauty and perfection would even travel in the linguistic realm, where the Old Persian word for a walled garden, Paridaida, would become adopted by many other Indo-European languages as the name for Heaven, a truly perfect and blissful realm.

This article shall explore the evolution of the garden from the Achaemenian (6th– 4th centuries BCE) to the Sassanian (3rdcentury BCE-7th century CE) empires. It will delve into how the Great Kings of Iran infused political and religious ideology with arboricultural, horticultural and artistic innovation. Finally, we shall observe how thousands of years of Persian tradition would be taken up and spread across the world in the wake of conquest and cultural renewal, shaping not only the garden but the very notion of an earthly paradise across Eurasia.

Paradise Begins

From humble roots as horse-riding nomads, the Achaemenian dynasty would, under the leadership of rulers such as Cyrus and Darius, forge the largest empire of the ancient world. This empire not only pioneered advances in art, architecture, and statecraft, but also took the first steps toward creating what would become the Persian garden.

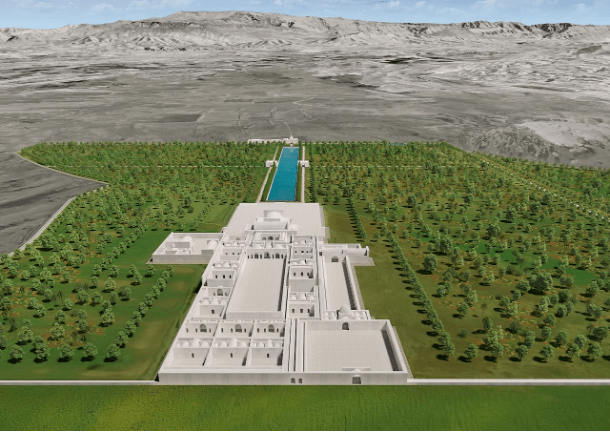

The earliest known example emerged at Pasargadae, the capital founded by Cyrus the Great. Within its vast palace complex lay two distinct parks. One was a royal hunting ground, home to wild animals pursued by the king, an activity long celebrated across ancient cultures as a symbol of martial prowess and divine sanction. The other, however, was a cultivated garden enclosed by walls and integrated into the palace precinct to grant the king a readily available view of it. Here, a network of stone water channels, fed by the nearby river via an underground irrigation system known as a qanat, divided the space into four equal parts, a layout that would later be known as the chahar bagh (Farsi for Four Gardens). The quadripartite design, lined with trees and filled with grasses and flowering plants, would become a defining motif of Persian landscape design. This model was replicated at other royal sites, such as Susa and Persepolis, and impressed contemporary Greek observers, including Xenophon, who said that they were “full of all things fair and good that the earth can bring forth”.

“Creating verdant, geometrically ordered landscapes amid arid terrain embodied the triumph of civilisation over chaos, an earthly reflection of cosmic order.”

While these gardens undoubtedly served as spaces of leisure, they also functioned as potent expressions of ideology. By gathering and nurturing flora from across the empire, the Great Kings demonstrated both the vastness of their dominion and the sophistication of their administration. Creating verdant, geometrically ordered landscapes amid arid terrain embodied the triumph of civilisation over chaos, an earthly reflection of cosmic order. Some scholars suggest that the division of the garden into four sections echoed one of the royal epithets, “King of the Four Quarters of the World”, a title they inherited from Ancient Mesopotamia, making the garden itself a political and cosmological statement. The use of gardens in such a manner indeed seems to have been inspired by the great Mesopotamian civilisations of Assyria and Babylon, whose traditions in fashion, iconography and statecraft influenced the Persians in no small measure. For example, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 669–631 BCE) meticulously described not only the majesty and fertility of his garden at Nimrud but that he also populated them with plants and cuttings obtained while on campaign. This served not only as a demonstration of Ashurbanipal as a bringer and carer of life but also as a reminder that his armies were powerful enough to subjugate the kingdoms from which some of his cherished plants hailed from.

Yet these gardens were not only political theatre; they were also spiritual spaces. The Great King’s role as cultivator and protector of life resonated deeply with Zoroastrian ideals of stewardship and the maintenance of asha, the concept of universal order and truth. Greek writers, too, noted the pride Persian monarchs took in their gardening, seeing it as both personal virtue and royal duty. Even the choice of plants carried symbolic meaning: lotuses, palms, and chamomile, all associated with purity, vitality, and divine favour, adorned both gardens and architectural reliefs, intertwining nature, faith, and kingship.

Paradise Endures

In 330 BCE, the Persian Empire would come to an end at the spear tips of Alexander of Macedon’s armies. His conquest has been viewed as a cataclysm in Iran, with the destruction of Persepolis being particularly viewed as a deep cultural wound. The Persian Gardens, however, would not share the same fate as the empire that birthed them.

There is evidence that aspects of earlier Persian gardening—particularly the use of enclosed, irrigated spaces—continued under the Seleucids after the fragmentation of Alexander’s realm, even if the highly formal four-part division of later Persian gardens is not clearly attested in this period. The next great power to rule Iran were the Parthians, a nomadic group who had thrown off Seleucid suzerainty and migrated into Iran from Central Asia. The Parthians’ semi-nomadic heritage, combined with their adoption of Hellenistic urban models, produced a fusion of traditions in their royal residences and capitals, such as Nisa and Hecatompylos, where cultivated and enclosed spaces likely formed part of larger palatial complexes and served to express continuity with earlier Achaemenid kingship.

The Parthians continued the broader tradition of walled and planted enclosures, though their gardens are more difficult to reconstruct archaeologically because of the predominance of mud-brick construction. Pavilions (kushk) appear to have been characteristic elements in some high-status compounds, functioning as places of retreat and ceremony. One of the clearest examples comes from Qaḷʿa Yazdegerd, where excavations have identified a fortified palace complex associated with an extensive garden and a pavilion. In many other Parthian sites, such as Nisa, the evidence for formal ornamental layouts, water basins, axial channels, or structured planting beds, is limited or uncertain.

Across the Parthian realm, the scale and layout of gardens varied with regional climate and cultural influence, but the ideal of the enclosed, cultivated paradise persisted. In this way, Parthian garden spaces, whether simple courtyards or more elaborate palatial enclosures, formed an intermediate stage between the expansive royal parks of the Achaemenids and the more formal, geometrically organised gardens of the Sasanians.

Paradise Blooms

In 224 CE, the House of Sassan, under its leader Ardashir (r. 211/2–224 CE), rose in revolt and overthrew the Parthians, marking the birth of the Sassanian Empire. Styling themselves as the restorers of Persian greatness after the centuries of foreign and fragmented rule, the Sassanians presided over a revival of Iranian culture and identity, one that profoundly shaped the evolving art of the garden.

The Sassanians retained many features of their predecessors’ landscapes. The fourfold division of space was maintained, along with pavilions placed at the heart of enclosed gardens. As before, plants and trees were gathered from across the empire to symbolize the reach and abundance of the King of Kings. Royal hunting parks also continued in the Achaemenian tradition, such as the famed example at the palace of Khosrow II at Qasr-e-Shirin. Yet, while they drew upon older traditions, the Sassanians also added new meanings and aesthetics into the tapestry of Persian garden design.

One of the most significant developments of the period was the formalization of Zoroastrianism as the state religion. The clergy’s growing influence at court left a distinct imprint on architecture and landscape alike. In many Sassanian palaces, notably at Firuzabad and Sarvestan, the spatial relationship between built and natural forms became more defined. Thick walls with few openings enclosed the royal pavilions, creating a deliberate boundary between human artifice and the sacred natural world beyond. This separation has often been linked to Zoroastrian cosmology: nature, a divine creation, was to be revered rather than dominated.

“Channels, pools, and fountains became central to Sassanian gardens, turning them into shimmering sanctuaries of purity and renewal.”

Equally important was the element of water, regarded in Zoroastrianism as holy and life-giving. Channels, pools, and fountains became central to Sassanian gardens, turning them into shimmering sanctuaries of purity and renewal. The palace of Ardashir I at Firuzabad and the gardens of Bishapur exemplify this emphasis, where intricate hydraulic systems and terraced layouts celebrated the spiritual and aesthetic power of flowing water, a tradition that would later flourish in the Islamic gardens of Iran and the wider Islamic world.

The Sassanians also displayed a sensitivity to the natural terrain. While preserving the geometric order of earlier layouts, they often adapted their plans to existing landscapes. At Firuzabad, the gardens followed the contours of a natural basin, while at Bishapur, engineers worked with the gradient of the valley to facilitate irrigation through gravity rather than intrusive earthworks. This blending of geometry and topography marked a mature stage in Persian landscape design, one that balanced order and nature, artifice and reverence.

Paradise: A Story of Growth

“The garden is breathing out the air of Paradise today”

-Hafez

From the moment of their inception, Persian gardens represented far more than a mere collection and arrangement of plants and architectural features. When Cyrus the Great commissioned the first Paridaida after founding the Achaemenian Empire, he created a space that reflected his new nation’s belief in the power of his rule but also his duty as a caretaker of life and a protector of worldly order. His creation survived the tumult of imperial downfall, finding purchase with the new rulers of Iran and evolving through their cultural influence. Finally, under the stewardship of the Sassanians, these earthly spaces would transcend the mortal plane, being ever more infused with Zoroastrian ideology to become havens of natural divinity and spiritual enlightenment.

Even when the Sassanian Empire fell, these earthly paradises would endure. From the fortresses of Grenada to the courts of Samarkand and the monuments of Mughal India, the Persian garden would take root and would continue to, as Hafez wrote, breath out the air of Paradise.

Milo Reddaway

Further Reading:

- Caneva, G., Lazzara, A. and Hosseini, Z., 2023. Plants as Symbols of Power in the Achaemenid Iconography of Ancient Persian Monuments. Plants, 12(23), p.3991.

- Evyasaf, R.S., 2010. Gardens at a crossroads: the Influence of Persian and Egyptian gardens on the Hellenistic royal gardens of Judea. Bollet Archeol, 1, pp.27-37.

- GOODARZI, V., 2017. An analysis of Iranian Gardening since the beginning of the achaemenid dynasty to the end of the Pahlavi era.

- Hamzenejad, M., Saadatjoo, P. and Ansari, M., 2022. A comparative study of Iranian gardens in Sassanid and Islamic era based on described heavens. Journal of Iranian Architecture Studies, 3(5), pp. 57-79.

- Moghaddasi, A. and Zamanifard, A., 2013. Paradise on the Earth: Role of water, tree and geometry in the formation of Persian Gardens. Scientific Herald of the Voronezh State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering. Construction and Architecture, (3), pp.63-71.

- Naghipourfar, K., 2015. Architecture History in Sasanid Era.

Leave a comment