Due to geographical factors, Korea was invaded on many occasions by neighboring countries, especially China, which borders the northern part of the peninsula, and Japan, an island nation just across the eastern sea. In the case of Japan, large-scale invasions such as the Imjin War (1592–1598) and the Japanese occupation (1910–1945) are the most notable, while many other, smaller incursions are recorded in historical sources. China’s invasions were more periodic and regular and began much earlier, according to the records. Often, the rise and fall of Korean states were intertwined with those of the Chinese states bordering northern Korea.

According to historical records, the first evidence of a Chinese invasion dates to the Gojoseon period—an early Korean state—around the 3rd century BCE, when Yan, a marquisate of the Zhou dynasty, sought to bring about the downfall of its overlord. Fearing retaliation from Gojoseon—an ally of Zhou—Yan attacked the Liaodong area occupied by Gojoseon and pushed its population further south. In 108 BCE, the Han dynasty, the first to unify the Chinese states, invaded and destroyed Gojoseon. Four commanderies were subsequently established by the Han in Korea. However, control over these commanderies gradually faded, and their authority did not extend south of the Han River, which now runs through the center of the capital, Seoul.

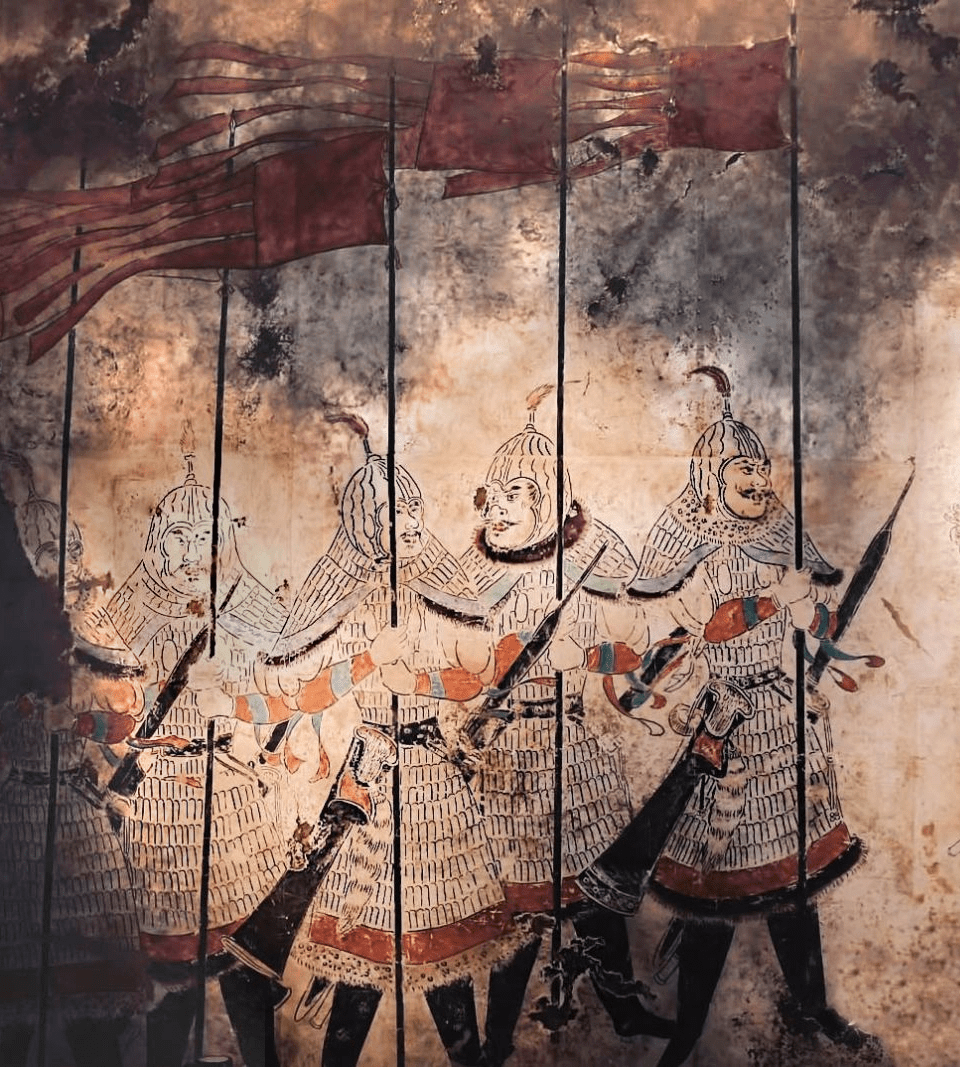

Today, Korea is divided into South and North Korea, but this has only been the case for about seventy years. Before that, a single dynasty governed the peninsula, from Goryeo (918–1392) to Joseon (1392–1897) and later the Korean Empire (1897–1910). By contrast, Korea prior to Goryeo was never fully unified. For example, the period of the Northern and Southern States (late 7th century–early 9th century) saw two competing states, while the period of the Three Kingdoms (1st century BCE–late 7th century CE) witnessed multiple rival polities. During these periods, the Korean states located in the northern part of the peninsula were never fully safeguarded against Chinese invasion. Among these, the most drastic were the Chinese invasions of Goguryeo, one of the kingdoms of the Three Kingdoms period, situated in northern Korea and bordering China and the northern tribes.

Patterns of Chinese invasions

The basic pattern of China’s invasions of Korea was twofold. In the first case, a unified dynasty was established in China and sought to expand its territory. This included the Han dynasty’s invasion of Gojoseon (1st century BCE), the Sui dynasty’s invasion of Goguryeo (around the turn of the 7th century CE), the Tang dynasty’s invasions of Goguryeo and Baekje (mid to late 7th century CE), the Mongols’ invasion of Goryeo, and finally the Qing invasion of Joseon (early 17th century CE).

The second pattern occurred when a tribe or state arose in northern China (north of Beijing) and expanded its power into the Chinese heartland. These invasions of the Korean Peninsula were motivated by the need to secure their rear against potential attacks from Korean states while challenging the existing Chinese dynasty. Notable examples include Yan’s invasion in the 3rd century BCE, the Khitan and Jurchen invasions during the Goryeo period (10th–14th centuries CE), and the Late Jin invasion in the early 17th century.

“Chinese aggression was not always successful”

Chinese aggression was not always successful. In particular, the invasions of Goguryeo by the Sui dynasty (581–618) and the Tang dynasty (618–907), from 598 to 661, ended in failure. Similarly, the invasions by the Khitan and Jurchen tribes during the Goryeo period were also repelled.

In the case of the Tang dynasty, after a couple of major failures (645, 661), it formed an alliance with Silla, one of the three kingdoms of Korea at the time. The joint forces were able to defeat Goguryeo after first conquering Baekje. Similarly, the Mongols’ invasion of Goryeo, the subsequent interference of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and the invasion of Joseon by the Later Jin (later the Qing dynasty) in the 17th century were all successful. The aftermath of these invasions was always significant for the parties involved. However, Korea’s national sovereignty remained largely preserved, except during the period of Yuan interference in the 14th century and the Japanese colonial rule in the early 20th century.

Invasions of the Tang in Korea

Emperor Taizong (r. 626-649), the second emperor of the Tang dynasty, which had united China for the third time in its history, invaded Korea in 645. At this time, Korea was in the Three Kingdoms period, consisting of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. Goguryeo controlled the area north of the Han River, Baekje the western region along the river, while Silla occupied the southeastern area, including the eastern part of the Han River basin and the eastern coastal region.

The Tang first attacked Goguryeo, driven by their ambition to establish hegemony over East Asia. Not only did Tang territory border Goguryeo, but Goguryeo was also a military power in Northeast Asia, having already defeated the Sui Dynasty some decades before the Tang invasion. The destruction of Goguryeo was thus a necessary step for the Tang Dynasty to expand its power in the region.

Since his accession to the throne, Taizong of Tang did not hide his intention to invade Goguryeo, unlike his predecessor. After destroying the Sui Dynasty and unifying mainland China, Tang under Taizong expanded its trade network westward along the Silk Road through conquest. Accordingly, if he were to occupy the Korean Peninsula—and even Japan to the east—he would control the entirety of East Asia. Tensions escalated between Tang and Goguryeo, but Yeon Gae So Mun, Goguryeo’s chief minister who held the real political power, did not yield. Yeon secured his position by replacing the king of Goguryeo in an unusual political coup d’état. Taizong of Tang, however, took this as a pretext to attack, invading Goguryeo by both land and sea.

Proceeding

The Tang invasions of Goguryeo proceeded in two stages: the first without the help of Silla, and the second with their support. Two large-scale invasions were carried out under the command of Tang Taizong (645 and 647), and another in 661 CE under Tang Gaozong (r. 649-683) after Taizong’s death. All of these were, however, defeated by Goguryeo—an unfortunate repetition of history, as China’s four previous large-scale invasions during the Sui Dynasty (598, 612, 613, and 614) had also failed.

The routes of invasion were similar to those used by the Sui Dynasty, and it is possible that the logistics of the ground forces and supplies were facilitated by the Grand Canal, completed during the Sui period.1 While the Tang army achieved some significant successes—such as breaking into the Liaodong Fortress, which the Sui army had been unable to penetrate—it was eventually defeated. The Battle of Ansi (located in the northwest of the peninsula) during the first invasion is particularly famous.

Emperor Gaozong (r. 649–683) of the Tang Dynasty, who ascended the throne after Tang Taizong, initially had no intention of going to war with Goguryeo. However, an unexpected opportunity arose. In 665, Yeon Gae So Mun of Goguryeo passed away, and his sons became embroiled in such an intense struggle that eventually one sibling requested Tang assistance. Goguryeo was weakening from within. Silla had already concluded a military agreement with the previous emperor, Taizong, to form a joint force. Persuaded by a Silla diplomat and high official, Gaozong agreed to attack first Baekje and then Goguryeo. Baekje fell to the allied forces of Tang and Silla in 660, followed by Goguryeo in 668. In the end, Tang’s invasion culminated in the unification of the Three Kingdoms in Korea under Silla’s hegemony.

Immediately after the conquests, Tang took control of much of the territory that had once belonged to Goguryeo. However, Tang clearly intended to assert control over the entire peninsula, now under Silla’s overlordship. Silla, naturally opposed to this encroachment on its sovereignty, engaged their previous allies in a series of battles, with the Silla army ultimately triumphing at the Battle of Maeso in 675.

Impacts

“The Tang invasions mark the last attempt by Chinese states, founded by southern Han tribes, to extend their influence into the Korean Peninsula.”

In the end, Tang conquered Goguryeo but failed to extend its power to the southern part of the peninsula due to its defeat by Silla. The territory of Goguryeo remained under Tang control only briefly, as its grip on these newly acquired provinces was weak. The descendants of Goguryeo held hostage by Tang eventually revolted and established a state called Balhae (698–926) in the former Goguryeo lands. Tang endorsed this new state, most likely because the region lay far from its capital, Xi’an, in the west of China. Meanwhile, internal problems began to trouble Tang, and interest in expansion to the east gradually waned. It should also be noted that Balhae, in the meantime, faced threats from the formidable tribes surrounding its territory—namely, the Mohe, Khitan, and Jurchen—which aligned with Tang’s interests. For the mainland Chinese regime, Balhae proved useful in keeping these tribes at bay. Like Goguryeo before it, Balhae initially boasted superior military and cultural power, but this Korean kingdom eventually fell to one of these tribes in 926.

“For the mainland Chinese regime, Balhae proved useful in keeping these tribes at bay.”

The Tang invasions mark the last attempt by Chinese states, founded by southern Han tribes, to extend their influence into the Korean Peninsula. The Song and Ming dynasties, two unified Chinese regimes established by Han, never ventured to invade Korea. In the end, it was the Chinese states founded by northern peoples—the Mongols, Khitans, and Jurchens—that would revive China’s interest in the peninsula.

Meanwhile, Silla brought an end to the period of the Three Kingdoms in Korea, which had lasted for seven centuries. However, their unification was limited. Not only had the territory shrunk, but much of northern Goguryeo later came under the control of the new Korean state of Balhae. Korea thus became divided into north and south, ushering in the so-called period of the Northern and Southern States in Korean history.

Silla adopted a relatively lenient policy toward the peoples of Baekje and Goguryeo. In fact, many of them fought alongside Silla in the struggle against Tang in 676. Over time, much of the Goguryeo population was assimilated into Balhae, while many Baekje people are believed to have migrated to Japan. Nevertheless, large numbers of both Goguryeo and Baekje inhabitants remained in their homelands, preserving their identities throughout the Silla period. In the early tenth century, their descendants rose in revolt against Silla, ushering in the short but turbulent era known as the Late Three Kingdoms. This period ended with the collapse of Silla and the rise of the new dynasty, Goryeo (918–1392). Goryeo revered Goguryeo as its predecessor and succeeded in reclaiming part of its former territory.

The impact of Tang’s invasions in Korea also reverberated in Japanese history, particularly through the fate of Baekje, Japan’s closest ally. The Japanese (Wa) dispatched troops to aid Baekje loyalists in their efforts to restore the fallen kingdom after its defeat by the allied Tang–Silla forces. While Japan had maintained diplomatic and cultural ties with all three Korean kingdoms, its strongest bond was with Baekje. The fall of Baekje alarmed the Japanese court, which feared the event might threaten their own security. The clashes between the Baekje–Wa alliance and the Tang–Silla coalition illustrate the geopolitical landscape of the period. The most decisive of these encounters was the Battle of the Baek River (663), where the Baekje restoration forces and their Japanese allies were decisively defeated. This loss marked the end of attempts to revive Baekje. At the same time, Baekje’s collapse compelled the Yamato government to adopt a more cautious diplomatic stance toward its East Asian neighbors. It also spurred significant political reforms, accelerating the development of Japan’s legal system and the centralization of state power.

Yonghyup Oh

Yonghyup Oh obtained a PhD in economic policy and worked at leading think tanks and universities. He is currently affiliated with the university of Antwerp. His varied research interests include Korean history and culture seen from a sustainability perspective.

Further reading

- Cohen, W. I. 2023. “Two Shadows Over Tang Splendor”. East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement with the World, New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press, pp. 62-88.

- Lai, C. 2020. Realism revisited: China’s status-driven wars against Koguryo in the Sui and Tang dynasties. Asian Security, 17 (2), 139–157.

- Holcombe, C. 2002. Immigrants and Strangers: From Cosmopolitanism to Confucian Universalism in Tang China.Tang Studies, 20, 71.-112.

- Kanagawa, N., 2020. “East Asia’s First World War, 643–668 CE” in S. Haggard & D. C. Kang (Eds.): East Asia in the World: Twelve Events That Shaped the Modern International Order, Cambridge University Press.

- Seo, Y. G. 2023. “Tang Dynasty’s Invasion of Goguryeo and the Oceanic Power”. The Journal of Northeast Asia Ancient History, 8:289-324. (in Korean)

- The Grand Canal of the Sui dynasty was established to link the north (Beijing) to the south (Hangzhou). It is approximately 1,800 km long. Rivers of China run from the west to the east. Creation of the North-South line could help procure rich southern agricultural products to the north. It is generally viewed that this canal was to facilitate Sui’s invasion in Goguryeo. ↩︎

Leave a comment