Master Kamal al-Din Behzād (1456–1535) was one of the most prominent painters (naqqāshs) active in the artistic circles of Herat and Tabriz during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, under the Timurid and Safavid dynasties. Born in Herat in 1456, he was orphaned at an early age and was probably raised under the guardianship of Āghā Mīrak Heravī, a painter who was likely his relative. At that time, Herat was the capital of the Timurid Empire. Behzād’s lifetime corresponded to the reign of Sultan Husayn Bayqarā (1469–1506) and the first thirty years of the Safavid era (after 1510). Approximately fifty years of his artistic career were spent in Herat, where he achieved full artistic maturity in Sultan Husayn Bayqarā’s court. Following the Safavid conquest of Herat in 1510, Behzād served in the Safavid royal atelier for nearly twenty-six years. Despite being one of the most celebrated artists of his time, only a few of his surviving works bear his signature: “ʿAmal-i al-ʿabd Behzād” (“The work of the servant Behzād”). His death occurred in Tabriz in 1535, as recorded by Dust Muhammad.

Masters and Artistic Formation

Behzād’s artistic development was profoundly influenced by masters such as Āghā Mīrak Heravī, Pīr Sayyid Ahmad of Tabriz, and Mawlānā Walīullāh. He learned the art of illumination (tazhib) from Rūhullāh Mīrak of Khurasan, and acquired his refined sense of brushwork and precision from Mawlānā Walīullāh. He gained recognition at around the age of twenty, developing his personal style between 1481 and 1488, and producing his most mature works from 1489 to 1510. In recognition of his artistic achievements, Sultan Husayn Bayqarā conferred upon him the title of “Kitābdār” (Keeper of the Royal Library). It is also reported that Behzād became part of the artistic circle of ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī, participated in his intellectual gatherings, and once drew Navāʾī’s portrait during a session, an act that earned him great admiration and solidified his reputation within Herat’s cultural milieu.

Source: tr.m.wikipedia.org

Source: wikiart.org

Head of Sultan Husayn Bayqarā’s Library

Following his experience in ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī’s atelier, Behzād was appointed head of Sultan Husayn Bayqarā’s royal library in 1484. Consequently, all artists working in the royal library and atelier came under his supervision, effectively making him the chief of court artists. Under his leadership, remarkable works were produced in the fields of book decoration and figurative painting. By 1485, at the age of thirty-five, Behzād had reached full artistic maturity and demonstrated the height of his creativity, especially in works commissioned by Sultan Husayn Bayqarā. Notable artists such as Hāji Muhammad Naqqāsh, Mawlānā Walīullāh, and Sultan ʿAlī Mashhadī were also active in the same atelier; however, Behzād held a leading position among them. He likely continued to serve in this post until approximately 1505, the year of the Sultan’s death.

The Period of Muhammad Shaybānī Khan (1507–1510)

Following the death of Sultan Husayn Bayqarā, Herat experienced internal unrest, and Badiʿ al-Zamān Mīrzā temporarily seized power. In 1507, Muhammad Shaybānī Khan conquered the city, prompting several artists to migrate to Bukhara, while Behzād is known to have remained in Herat. Owing to Shaybānī Khan’s favorable attitude toward artists, Behzād was able to continue his artistic activity. Indeed, the inscription “al-ʿabd Behzād” found on the surviving portrait of Shaybānī Khan is considered evidence of their connection. According to some sources, Behzād spent a short period in Bukhara during this time, and after Shaybānī Khan’s death in 1510, he moved to Tabriz, where he entered the service of the Safavid court.

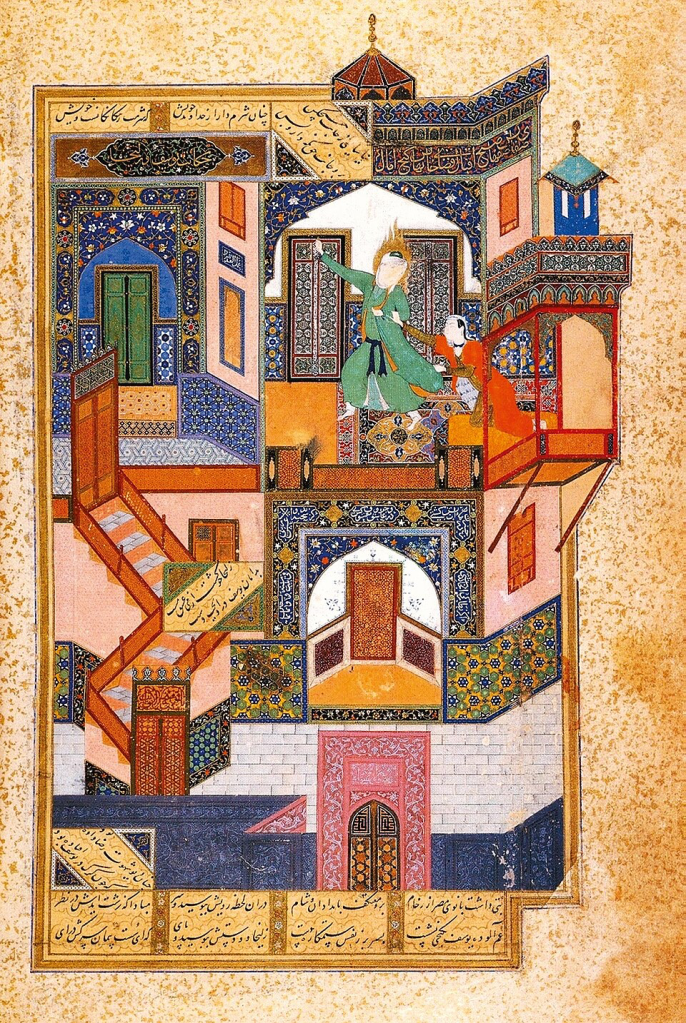

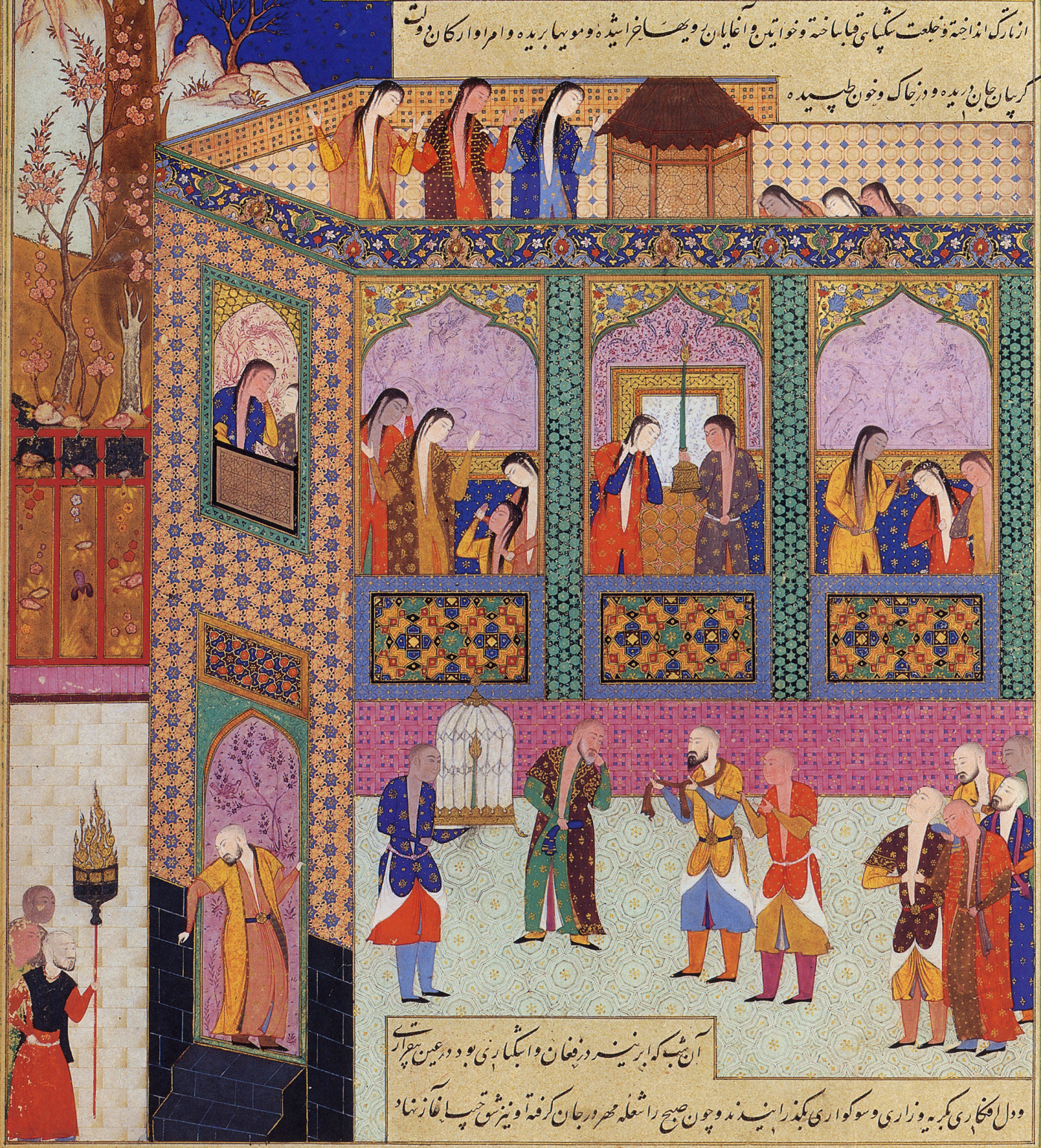

Saʿdī of Shiraz’s Bustan: “Joseph Tempted by Zulaykha”

Behzād’s mastery and his ability to captivate the viewer are most vividly demonstrated in his celebrated miniature “Joseph Tempted by Zulaykha” from Saʿdī of Shiraz’s Bustan. In this painting, Zulaykha has prepared a setting of seven rooms with closed doors to seduce Joseph. Behzād demonstrates exceptional skill in the visual narration of this episode: the carefully arranged stairways, the precise placement of doors and walls, and the varied decorations of each chamber all emphasize Joseph’s sense of confinement and astonishment. The depiction of Joseph unlocking a door and Zulaykha’s movement toward him adds dynamism and emotional tension to the composition. In designing Zulaykha’s palace, Behzād skillfully employed illumination techniques, displaying his remarkable sense of design and brush control through intricate patterns on the doors and walls. The work bears his signature: “ʿAmal-i al-ʿabd Behzād” (“The work of the servant Behzād”).

“he was not only an artist but also a powerful institutional figure within the Safavid court bureaucracy.”

Behzād’s Position in the Safavid Court

After Shah Ismāʿīl conquered Herat in 1510, he took Behzād and several distinguished artists with him to Tabriz. Subsequently, in 1515, he appointed his two-year-old son as the governor of Herat and sent Behzād together with Sultan Muhammad Naqqāsh from Tabriz to Herat, instructing them to teach painting to Prince Shah Tahmāsp. Later, in 1522, Behzād returned to Tabriz with Shah Tahmāsp and was appointed by Shah Ismāʿīl as the head of the Safavid Royal Library (Kitābkhāna). The library in Tabriz had initially been directed by Sultan Muhammad Naqqāsh, but soon came under the administration of Kamal al-Din Behzād. By royal decree, all artists and craftsmen working in the library, including calligraphers, painters, illuminators, gold beaters, and lapis-lazuli pigment preparers, were placed under Behzād’s authority. This demonstrates that he was not only an artist but also a powerful institutional figure within the Safavid court bureaucracy.

“Under Behzād’s supervision, one of the greatest artistic undertakings of the period, the “Shah Tahmāsp Shāhnāma”, was produced.”

The Relationship between Shah Tahmāsp and Behzād

During the reign of Shah Tahmāsp (r. 1524-1576), Behzād continued to serve as director of the royal library. He enjoyed the Shah’s personal favor and protection, and his artistic activities were directly supported by the ruler himself. Under Behzād’s supervision, one of the greatest artistic undertakings of the period, the “Shah Tahmāsp Shāhnāma”, was produced. In his later years, Behzād maintained close friendships with artists such as Sultan Muhammad and Āghā Mīrak. A handwritten letter from Shah Tahmāsp to Behzād has survived to the present day; its contents reveal that Behzād, in his old age, suffered from physical weakness yet continued to be held in high esteem by the Shah.

Characteristics of Behzād’s Works

According to Bahari (1996, p. 47), Behzād’s pictorial style can be classified into four main categories in terms of content:

- Realistic and vivid portraits or event scenes,

- Realistic yet imaginative interpretations of historical events,

- Illustrations of classical literary works, such as Niẓāmī’s Khamsa, ʿAṭṭār’s Conference of the Birds (Manṭiq al-ṭayr), and Saʿdī’s Bustan,

- Independent (non-textual) compositions, often allegorical or imaginative scenes, such as The Throne of Solomon and Bilqīs.

The most distinctive feature of Behzād’s paintings is their “poetic realism”, which conveys the factual nature of events in meticulous detail while also carrying symbolic meaning. Behzād approached his subjects like a documentary observer, depicting the everyday life, social relations, and architecture of his time with remarkable precision. Humans, animals, and natural elements are rendered with their own characteristic traits, and the figures are infused with movement and vitality. His figures are typically portrayed within the context of daily life, labor, and social interaction. The compositions are often arranged in a circular rhythm, generating a sense of movement across the pictorial space. This structural coherence later became a model for subsequent generations of artists.

Behzād’s approach introduced a humanistic perspective to Persian miniature painting. By incorporating human behavior, professional activity, social roles, and ordinary individuals into his compositions, he expanded the thematic scope of miniature art beyond the confines of courtly and mythological subjects. For instance, scenes such as a Black laborer pushing a wheelbarrow on a construction site, men carrying a funeral bier, or servants hanging towels in a bathhouse or drying their master’s feet exemplify his observational realism and social sensitivity. His understanding of color also marked a turning point in Persian miniature painting. In his works, color and form are inseparable, and he often employed flat, monochromatic backgrounds suited to the theme of the scene. By skillfully juxtaposing complementary colors, Behzād achieved harmony and depth. His palette includes a rich variety of blue, green, red, orange, yellow, brown, and gold tones.

“Behzād’s approach introduced a humanistic perspective to Persian miniature painting”

Behzād’s artistic vision was also influenced by the aesthetic and spiritual values of the Naqshbandī circles active in Herat. In the late 15th century, this Sufi order, through intellectual figures such as ʿAlī Shīr Navāʾī and Jāmī, deeply shaped Behzād’s artistic philosophy. Consequently, his paintings often emphasize Sufi symbolism, the balance between inner meaning and outward form, and moral and spiritual themes. Behzād never sacrificed the spiritual essence of a subject for the sake of its aesthetic appearance. In mystical scenes, he deepened the interplay between meaning and form. For example, in the abovementioned Bustan illustration, the interconnected rooms, locked doors, and stairways symbolically represent Joseph’s difficult escape from Zulaykha’s temptation. In this sense, Behzād can be regarded as one of the first artists to merge visual narration with moral and mystical depth.

Behzād’s Works during the Safavid Period

One of the earliest illustrated manuscripts produced under the Safavid royal library was the copy of the “Shāh Ṭahmāsp Shāhnāma” (Book of Kings), created under the supervision of Kamal al-Din Behzād. The manuscript was illustrated and richly decorated under Behzād’s direction, with the collaboration of Sultan Muhammad Naqqāsh, Āghā Mīrak, and many other painters and illuminators. At that time, most manuscripts were written in Herat, then sent to Tabriz for illustration. The calligraphic and decorative style of these manuscripts reflected the influence of the Herat school in the early Safavid period. Even after the transfer of artists to Tabriz, Herat continued for a long time to be recognized as a major center of manuscript production, where renowned calligraphers and book artisans of the era were active.

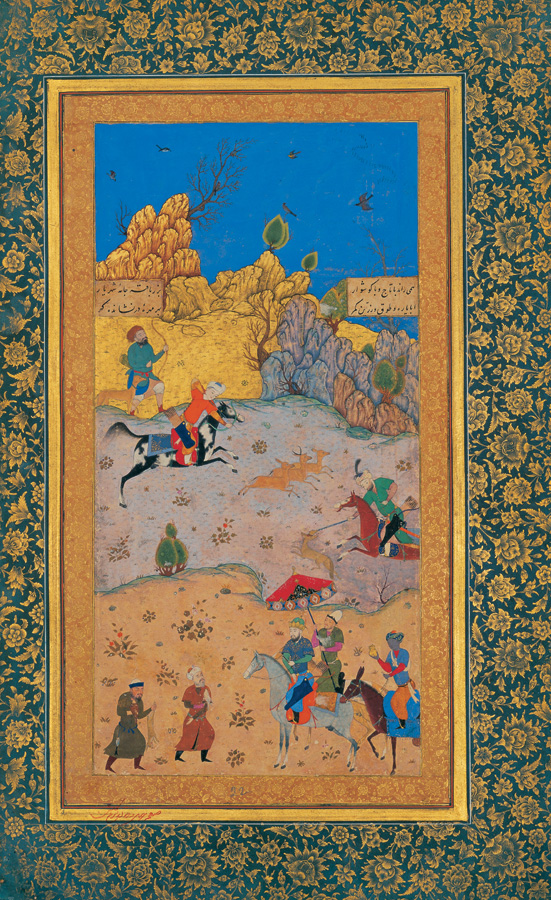

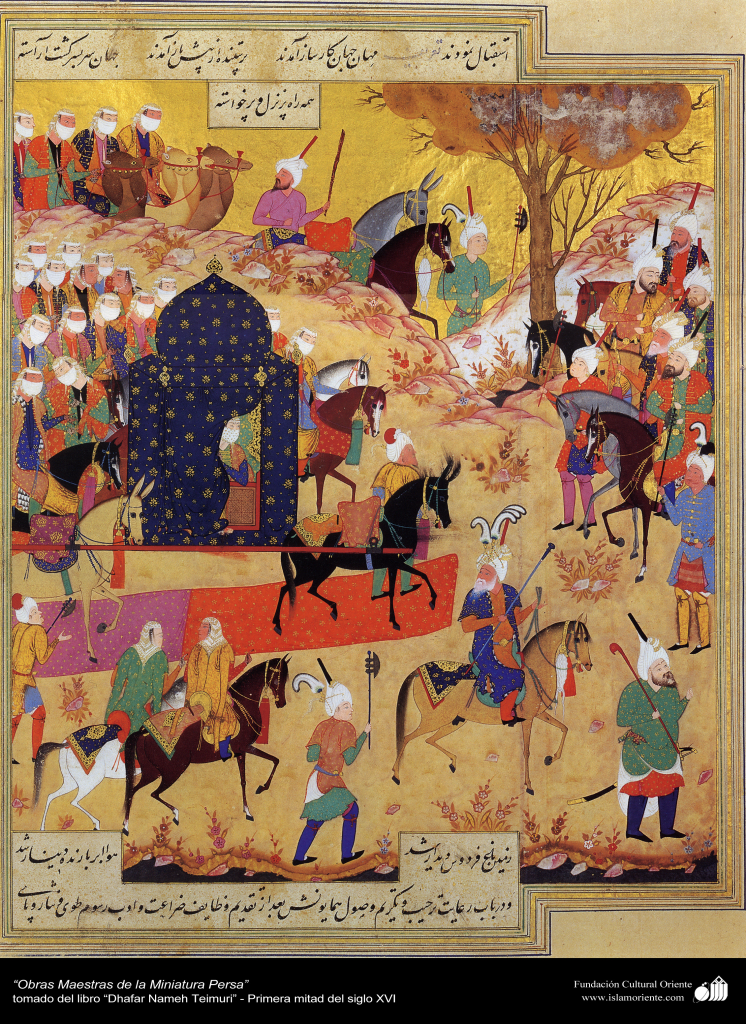

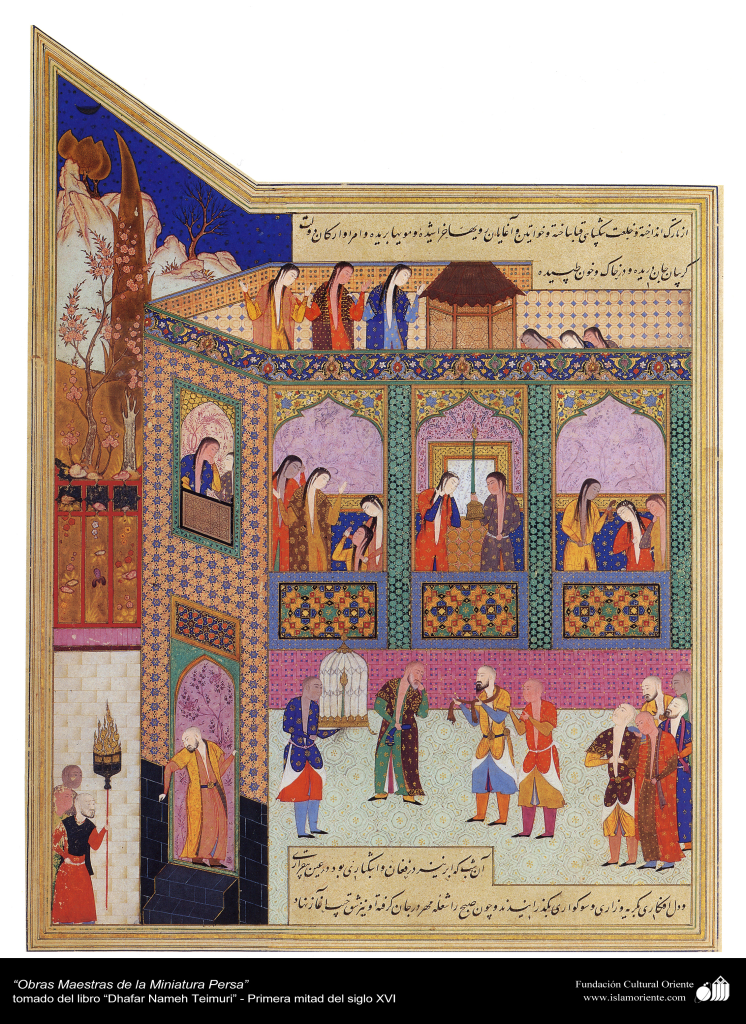

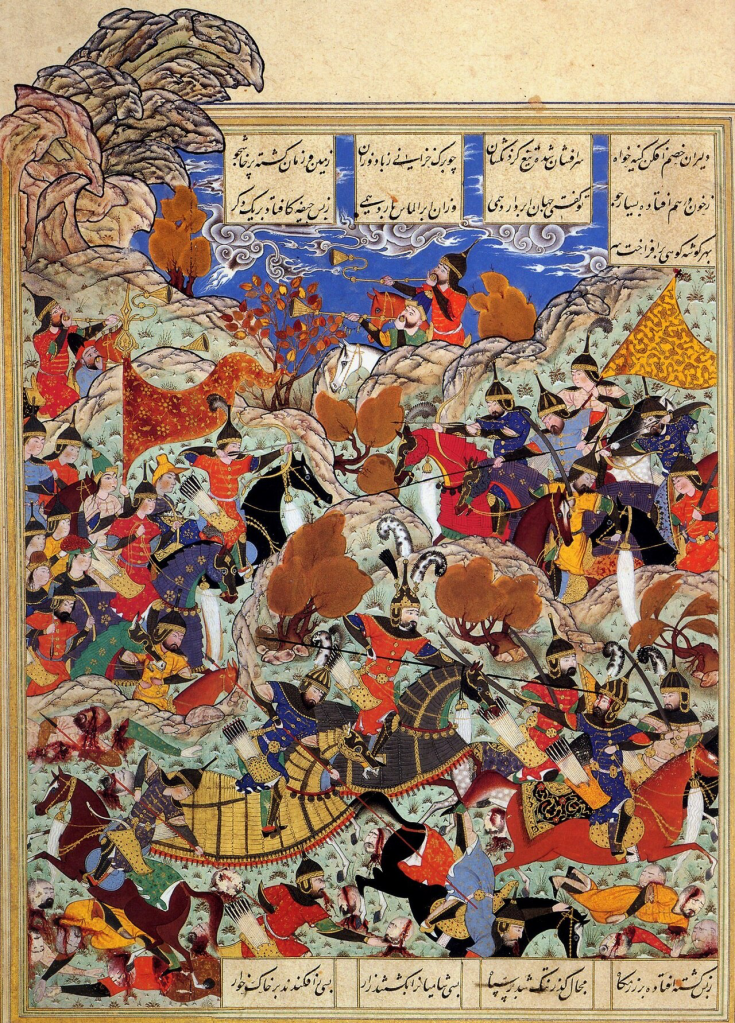

Zafarnāma of the Timurid Period (Golestan Palace Library, Tehran)

Another manuscript to which Behzād made significant contributions was the Zafarnāma currently residing in the Golestan Palace Library in Tehran. The Zafarnāma (“Book of Victories”), written by Sharaf al-Din ʿAlī Yazdī (died 1454), recounts the conquests of Timur (1320s-1405), the founder of the Timurid Empire, and stands among the most frequently illustrated historical texts of the Timurid period. The manuscript project was initiated in Shiraz under the patronage of Prince Ibrāhīm Mīrzā (1394-1434), taking four years to complete, and was finished in 1425. The book narrates Timur’s life in detail, from his birth to his death. Before Yazdī’s version, there existed an earlier chronicle titled Zafarnāma-yi Shāmī or Tārīkh-i Futūḥāt-i Amīr Tīmūr Gūrkān, written in Uighur script by Niẓām al-Dīn Shāmī. Yazdī’s Zafarnāma manuscript consists of 750 folios, each containing nineteen lines written in nastaʿlīq script. The elegant calligraphy of this rare manuscript was completed in 1529 by Sultan Muhammad Nūr Muzahhib. Before the main text, the opening four folios are illuminated with gold embellishments and a Simurgh motif, executed by Mīr Azūd-i Muzahhib. In this and subsequent manuscript copies, there are a total of twenty-four miniatures depicting court ceremonies and battle scenes, produced with exceptional artistic refinement.

Shadabeh Azizpour

Shadabeh Azizpour is an art historian specializing in Persian and Turco-Persian miniature painting and early Islamic visual culture. She holds a PhD in Art History, with research focusing on manuscript production, artistic exchange, and the mobility of visual forms across Iran plateau, Anatolia, and the broader Persianate world. Her work combines visual analysis, codicology, and cultural history to examine how illustrated manuscripts functioned as sites of artistic innovation and cross-regional interaction. Her broader research interests include courtly painting, transimperial artistic networks, and the relationship between image, text, and knowledge in the early modern Islamic world. Her research also explores the history of medieval architecture in the Iranian plateau, Central Asia, and Anatolia, with particular attention to the relationships between architectural space, manuscripts, ornament, and visual culture.

References

- Ashrafi, M. (2007). Behzād va shekl-gīrī-ye maktab-e mīnīyatūr-e Bukhārā dar qarn-e 16 mīlādī [Behzād and the formation of the Bukhara miniature school in the 16th century]. Tehran: Moʾasses-e Taʾlīf, Tarjome va Nashr-e Āsār-e Honarī Matn.

- Azhand, Y. (2016a). Negārgari-e Irān (Vol. 1). Tehran: Sāzmān-e Samt.

- Azhand, Y. (2016b). Negārgari-e Irān (Vol. 2). Tehran: Sāzmān-e Samt.

- Azizpour, S. (2024). Safavid schools of depictions (Doctoral dissertation, Erciyes University). National Thesis Center of Türkiye (YÖK).

- Bahari, E. (1996). Behzad, Master Iranian Painter. Islamic Azad University (Shabestar). [Persian]

- Francis, R. (2004). Jelvehā-ye honar-e Pārsi: Nuskhehā-ye nafis-e Irānī, qarn-e 6–11 hijrī-ye qamarī, mojūd dar ketābkhāneh-ye Faransah [Persian artistic brilliance: Precious Iranian manuscripts from the 6th to 11th centuries AH, preserved in the French Library] (A. Rouhbakhshan, Trans.). Tehran: Sāzmān-e Chāp va Enteshārāt-e Vezārat-e Farhang va Ershād-e Eslāmī.

- Gelibolulu, Mustafa ʿĀlī. (1926). Menāqıb-ı Hünerverān. Istanbul: Matbaa-ı ʿAmire.

- Gelibolulu, Mustafa ʿĀlī. (1982). Hattatların ve Kitap Sanatçılarının Destanları (Menāqıb-ı Hünerverān) (M. Cunbur, Ed.). Ankara: Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Yayınları.

- Ghaffārī Qazvīnī, Q. A. (1964). Tārīkh-e Jahān Ārā. Tehran: Ketābforooshi Hāfez.

- Govashani (Govāshānī), D. M. (1999). Dust Mohammad Govashani. Tehran: Amir Kabir.

- Grube, E. J. (1968). The Classical Style in Islamic Painting. Germany: Edizioni Oriens.

- Khandmir, G. I. H. (1954). Habīb al-Siyar fī Akhbār Afrād al-Bashar (Vol. 3). Tehran: Khayyām Publishing.

- Kumī, G. A. (1973). Golestan-e Honar. Tehran: Bunyād-i Farhang-i Īrān.

- Kumī, G. A., & Ahmet, G. (2004 [1383 AH]). Gülistān-i Hüner (A. Süheyli Hānsārī, Ed.). Tehran: Neşr-i Menuçihri.

- Mayel Heravī, N. (1993). Ketāb-e Ārāyī dar Tamaddon-e Eslāmī [Book Decoration in Islamic Civilization]. Mashhad: Āstān Qods Razavī.

- Mirjafari, H. (2000). Tārīkh-e Tahavvolāt-e Sīyāsī, Eghtesādī, Ejtemāʿī va Farhangī-ye Irān dar Dore-ye Tīmūriyān va Torkamānān [The Political, Economic, Social, and Cultural Transformations of Iran during the Timurid and Turkmen Periods]. Tehran: Dāneshgāh-e Esfahān & SAMT.

- Rajabi, M. A., & Hosseini Rad, A. (2005). Shāhkarhā-ye Negārgari-ye Irān [Masterpieces of Persian Painting]. Tehran: Moʾassese-ye Toseʿe-ye Honarhā-ye Tajassomī. [In Persian]

- Thackston, W. M. (2001). Album Prefaces and Other Documents on the History of Calligraphers and Painters (Vol. 10). Leiden: Brill.

- Turkmān, I. B. M. (1896). Tārīkh-e ʿĀlam Ārā-ye ʿAbbāsī. Tehran: Amīr Kabīr.

Leave a comment