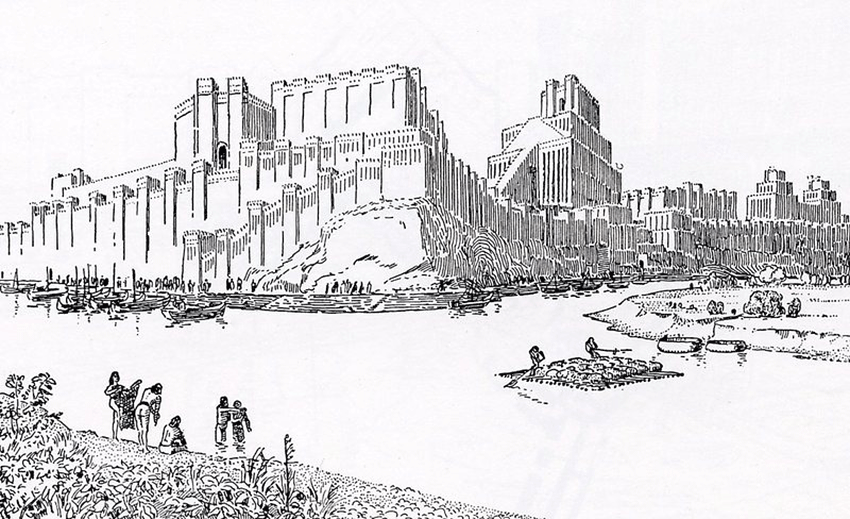

Sailing up the Tigris from the south, one of the many great spectacles that awaited ancient travellers was the awe-inspiring sight of Aššur’s ziggurat, visible from far away, arising atop a 40 meter high cliff that dominated the landscape. This structure was the ultimate proof of the Assyrians’ dedication to their patron god, who not only embodied the synonymous city of Aššur, but also represented the power of the Assyrian empire itself. Who was this Aššur? How was he envisaged by his worshippers and what importance did he carry for them? As we shall see momentarily, this proves to be a much harder question than one might expect.

Aššur’s Origins

The god Aššur’s origins are shrouded in mystery. It has been particularly challenging for researchers to trace the deity’s origins, given the city of Aššur’s reluctance to yield any valuable information on its earliest history. Non-stop building activities over the course of centuries have almost completely destroyed, replaced or hidden the original town that arose alongside the banks of the mighty Tigris. Nevertheless, the city of Aššur must have been already a town of special significance by 2500 BCE, luring early settlers to its confines due to its favourable position on the crossroads of various trade routes. The location also proved to be easily defendable, with a 40-meter high triangular rocky crag, the Qal’at Sherqat, called Abiḫ in ancient times, marking out the location vividly among the flat surroundings. All of this made the site an excellent choice of settlement.

“This has entertained a theory in recent decades that the god played merely a peripheral role back then.”

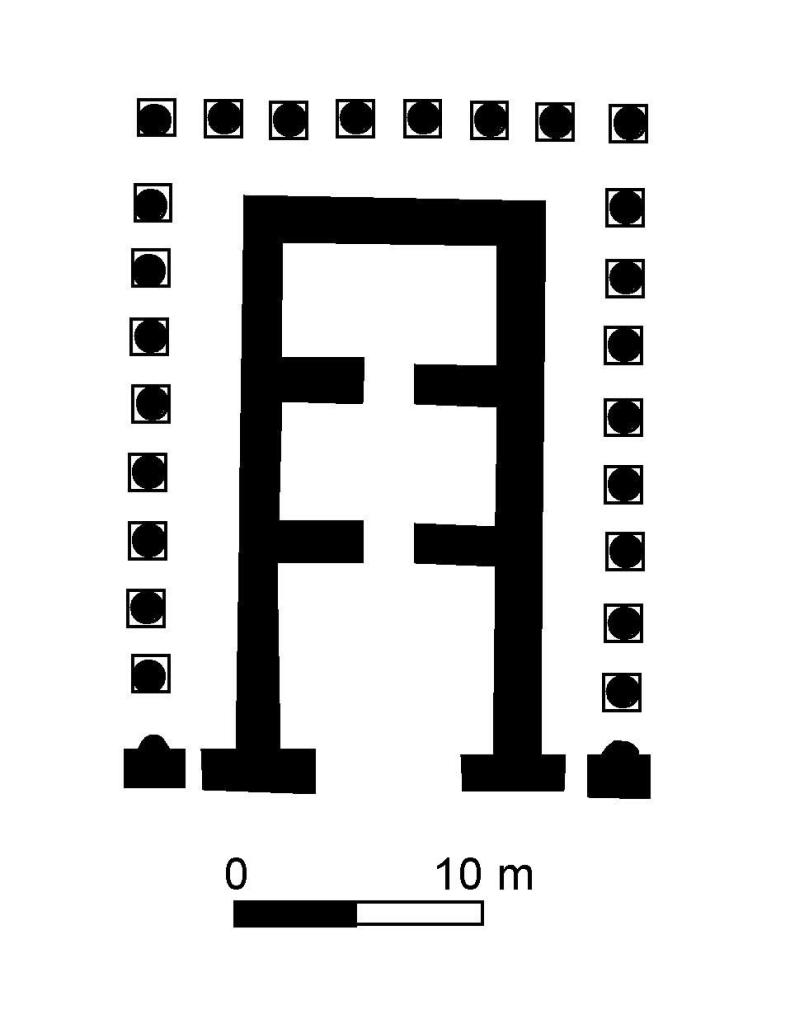

There has been one discovery which sheds a faint light on the religion of the oldest inhabitants of the city. In the northern part, a structure had been unearthed which many archaeologists believed to be the temple of the so-called “great goddess”, who later came to be identified with Ištar.1 There are strangely no traces, however, of Aššur during these early stages of the town’s history. Even the famed northeastern cliff upon which the famed temple and ziggurat of Aššur would proudly stand, reveals no significant building activity between 2500 and 2100 BCE.2 This has entertained a theory in recent decades that the god played merely a peripheral role back then.3 The Assyrian belief system was instead dominated by the aforementioned “great goddess”, making early Aššur more akin to other North-Mesopotamian settlements in terms of religion.4 Despite the theory’s sound reasoning, we have to remain cautious, however, as the scarcity of available material doesn’t give us exactly the luxury to come forward with any bold statements on the 3rd-millennium Assyrians and their religious beliefs.

The ruler who is said to have initiated construction on the god’s great temple on the Qal’at Sherqat was the 16th king of the Assyrian King List, Ušpia. He was the leader of the Assyrians perhaps during the late 22nd and 21st century BCE and was believed to have been the second last of the so-called “kings who lived in tents”. Although no archaeological evidence can confirm this attribution, it is generally accepted that the god Aššur had indeed received his own abode by the late 3rd millennium. It is unclear whence this deity came, as his name does not lend itself to any credible etymological explanation.5 Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the city gave its name to the deity or the other way around. There is no good reason, however, to assume any other origin of the god than with the Assyrians themselves, with the likes of Knut Leonard Tallqvist, Wilfred George Lambert and Karen Radner considering Aššur intrinsically Assyrian.6

The northeastern crag of Qal’at Sherqat (Abiḫ) was closely interwoven with the cult of the god Aššur. As one inscription from the reign of king Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. 1233-1197 BCE) reads: “the lord of the mountain Abiḫ, loved his mountain.”7 This is quite ironic given the fact that it was Tukulti-Ninurta I who tried to dislodge Aššur when he temporarily moved the Assyrian capital three kilometres upstream on the opposite bank of the Tigris and founded a new temple -albeit of modest size- for the god there. This was an act which was met with serious resistance and greatly contributed to his poor reputation.8 It was, in fact, not only blasphemous but also illogical to revere him anywhere else but in the city of which he was the personification and protector. Even when the kings’ ambitions had outgrown the relatively small confines of Aššur during the Neo-Assyrian period (911-609 BCE), leading them to move their capital elsewhere on multiple occasions, the city and the temple of Aššur still remained the religious and ideological heart of the kingdom, with the Neo-Assyrian rulers consistently abstaining from establishing a new sanctuary for their supreme deity in any of their new cities.

The close association of the god with the city as a concrete space is also highlighted in other sources. For example, at the ending of his name we sometimes encounter the cuneiform determinative sign of a location, while a clear reference to the city is at times introduced with the cuneiform determinative sign of divinity instead of location. Assyrian names such as Aššur-šaddî-ili (‘the god Aššur is a divine mountain’) and Aššur-duri (‘Aššur is my fortress’) also confirm the perception of the god as a physical space.9 Finally, we have also unearthed an ancient depiction, probably dating to the Old Assyrian period, which represents Aššur partly human-shaped and partly mountain-shaped.10

The Old Assyrian Period: The Rise of a Faceless God

“He was a faceless and abstract power as opposed to the other well-defined deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon.”

Once we enter the Old Assyrian Period (c. 2025 – c. 1364 BCE), things gradually become clearer. Treaties and royal inscriptions started referring to the god frequently, with the monarchs legitimizing their rule through him.11 They presented themselves as “Aššur’s Stewards” (waklum, “overseer”, or rubā’um, “the great one”), chosen by him to rule the city in his stead and to defend his interests.12 The sincerity of this ideology can be gathered from the fact that the city’s rulers refrained from taking up the title šarrum (king in Akkadian) until the Middle Assyrian Period (c. 1363 – 912 BCE), believing Aššur to be the one, true king.13

This stewardship meant that the Assyrian ruler simultaneously served as the city’s high priest, thus dominating both political and religious life in ancient Assyria. It was therefore his responsibility and privilege to maintain and -if possible- expand the god’s worship as well as to foster the god’s good will toward the city and its inhabitants. An integral part of this duty consisted of keeping his temple in good shape, an activity to which various royal inscriptions proudly refer. Without the steward, the religious worship of Aššur was impossible, however, reflected by the fact that the New Year’s festival, for example, could not be celebrated in his absence.14

This religious-political ideology can be traced back to the 21st century BCE, at a time when Aššur regained its independence from the powerful Ur III dynasty which had ruled Mesopotamia for over a century. A seal inscription which reveals the origins of this ideology was unearthed at the Anatolian city of Kaneš in one of the letters from the local Assyrian merchant community.15 The tablet contained a seal impression belonging to a certain Assyrian ruler from the 21st century BCE called “Silulu, son of Dakiku”, who might be identified with the Sulili of the Assyrian King List. The inscription starts with the simple phrase, “Aššur is king”, emphasizing Aššur’s true power, while he himself held mere stewardship. It had been suggested that this ideology originated in the southeastern Tigris region, more specifically in the city of Ešnunna.16 Ešnunna was a city-state with cultural ties to Aššur, where the supreme god Tišpak was likewise revered to as “king”, while the ruler served as his “steward”.

Another interesting early source comes a few decades later, dating to the reign of king Erišum I (r. c. 1974 – c. 1935 BCE). Despite the original inscription being lost to the ravages of time, two copies have survived:

“May just prevail in my city! Aššur is king! Erišum is Aššur’s Steward! Aššur is a swamp that cannot be traversed, ground that cannot be trodden upon, canals that cannot be crossed. He who tells a lie in the Step Gate, the demon of the ruins will smash his head like a pot that breaks”17

The so-called Step Gate, to which the final line refers, was the place in the city where justice was administered. The inscription supposedly stood in or near this building, warning the litigants not to tell any lies to the judges under pain of divine punishment. Once again, we see the motive of stewardship appear.

The above text also perceives the god as some natural force, reflecting another important trait of Aššur: he was a faceless and abstract power as opposed to the other well-defined deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon. Aššur initially did not in appear in any mythical stories and wasn’t connected to any genealogy, bereft of a spouse and children. He was simply the supreme divine power of the universe, something which makes him especially interesting to researchers of the history of religion, reminding us in a way of the all-encompassing, abstract gods of the monotheistic religions.

Aššur’s Journey to Supremacy

This did not mean, however, that everyday Assyrians didn’t have the proclivity to visualize the god in more comprehensible terms. There is proof that already during the Old Assyrian period (c. 2025 BC–c. 1364 BCE), Aššur received some concrete features which facilitated imagining him. A seal impression from the 18th century BCE, found at Acemhöyük, represents the god as a four-legged rock – perhaps in reference to the Qal’at Sherqat crag – with the head of a bull. The attribution of bovine features to Aššur was certainly not an isolated incident here, as his temple was also called the “House of the Wild Bull and the Lands” (Eamkurkurra) during Erišum’s reign in the 20th century BCE. The equation with a bull shouldn’t come as a surprise, however, as this animal was a well-established symbol of royal power since at least the days of the Akkadian empire (c. 2334 – 2154 BCE).18 Furthermore, correspondence from Kaneš informs us that Aššur could be anthropomorphised by his worshippers.19 Herein, an Assyrian merchant complains about the theft of the sun disk from the breast of Aššur’s cult statue as well as of his sword, a possible reference to the existence of representation in (partly?) human form.20 This passage is problematic, given the previously stated immobility of the god: the presence of a cult statue of Aššur in Anatolia seems to contradict this. However, the god could be represented elsewhere through ceremonial weapons which were believed to belong to Aššur, with the local population swearing oaths by them.21 Still, the passage seems to refer to an actual statue of the deity, leaving the present author with more questions than answers.

More significant in Aššur’s slow but sure development into a well-defined god were the frequent attempts to identify him with other Mesopotamian deities. This religious assimilation was made all the easier by his vague character, enabling him to absorb other deities and their stories with remarkable ease. Although evidence suggests that earlier attempts were made of assimilation with the Amorite god Dagan, the legendary ruler of North Mesopotamia, Šamši-Adad I (r. ca. 1808-1776 BCE) can be credited with the first successful policy of assimilation, one that would completely alter the god’s image and theology.22 He, in fact, equated Aššur with none other than the head of the Babylonian pantheon, Enlil, whose worship was centred at Nippur. When Šamši-Adad I rebuilt the temple on the Qal’at Sherqat on a monumental scale, he dedicated the new sanctuary to Enlil. This by no means meant the replacement and abolishment of the cult of Aššur, but quite simply expressed his conviction that Aššur was Enlil himself.23 This entailed a great challenge to Nippur’s status as the religious heart of the land between the Tigris and Euphrates. The assimilation had far-reaching consequences for the conception and theology of Aššur, with the Assyrian god assuming many of Enlil’s titles, such as “the great mountain” and “the wild bull”. Also, like Enlil, Aššur started being represented in the company of a spouse, Mullissu, the Assyrian counterpart of Ninlil, Enlil’s wife.24

One consequence of major importance in the assimilation of Aššur with Enlil lay in Assyrian state ideology. During the Middle Assyrian period (c. 1363–912 BCE), we encounter for the first time the yearly offerings each dependent territory of the empire had to make not to the king, but to Aššur and the other gods who resided at his temple.25 The yearly contribution quota were rather modest in size and could have surely been provided by the city and its hinterland, revealing the ideological nature of the procedure. It was important for the Assyrian provinces to do so, as it formed some sort of subjugation ritual to the god Aššur and therefore also to the Assyrian state and its ruler. Consequently, failure to comply could be regarded as an act of rebellion and was met with severe punishment. This practice was not invented by the Assyrians however, but dated back to at least the 21st century BCE, when the Ur III dynasty also demanded yearly offerings to Enlil at Nippur by its governors and subjugated rulers, symbolizing their allegiance to the established order. This subjugation ritual reached its peak during the Neo-Assyrian period, when it spread throughout the entire Ancient Near East in the wake of the rampaging armies of Assyria. For example, after Esarhaddon (r. 680-669 BCE) had conquered Egypt, he ordered its governor to provide “in perpetuity regular offerings for Aššur and the great gods”.26

“Thus, Assyria’s nemesis, Babylon, had successfully toppled Aššur’s reign in the world of the gods. Aššur, however, rose to the challenge to restore his supremacy.”

Šamši-Adad’s religious policy of assimilation with Enlil in all likelihood inspired King Hammurabi (r. c. 1792 – c. 1750 BCE) to do the same for his city’s patron deity, Marduk. He crowned Babylon the new Nippur and transferred the so-called “Enlilship”, that is the supreme power over the world, to Marduk.27 Hammurabi’s religious policy was a success, with Marduk henceforth being regarded by many as the foremost deity of Ancient Iraq up until the late 1st millennium BCE. Thus, Assyria’s nemesis, Babylon, had successfully toppled Aššur’s reign in the world of the gods. Aššur, however, rose to the challenge to restore his supremacy. This came in earnest under King Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE) with a religious dialogue of a remarkably aggressive nature, reflecting the tense rivalry between Assyria and Babylonia. A cultural war was waged by the Assyrians against Babylon in which they aimed to usurp Babylonia’s cultural supremacy by dethroning Marduk and recrowning Aššur the head of the divine world. In an act that must have shocked the Babylonians, the Assyrian king had Marduk’s ritual bed symbolically removed from the Etemenanki, the legendary ziggurat of Marduk, and brought to Aššur’s sanctuary in an act which Eckart Frahm called “cultural cannibalism”.28 Furthermore, the Assyrians tried to promote Aššur as the real creator of the universe by copying the famed Babylonian creation poem Enūma Eliš and simply replacing Marduk’s name with that of Aššur.29 Finally, Marduk, also influenced and altered the visual representation of Aššur, with the Assyrian god appearing with a snake-dragon, the traditional mythical companion of the god Marduk.

The Fall of Aššur the City and the God

Despite its formidable fortifications, the city of Aššur fell in 614 BCE at the hands of the Median king Cyaxares, shortly after which the Assyrian Empire collapsed as well, never to rise again. The damage to the city was enormous, and Aššur’s splendid temple and ziggurat were razed to the ground. The popularity of the god inevitably waned, but his cult did not disappear, as one might expect with a deity so closely associated with a state that was now defunct. Despite the massive destruction caused by Aššur’s enemies, the city remained inhabited, albeit on a modest scale. The surviving population erected a small sanctuary atop the rubble of the great temple, where they continued to worship their god.

Later, during the 1st century BCE, Aššur again became a vibrant city under Parthian rule, with the local governor even having a new temple built for “Assor” in a Hellenized style. Despite these positive signs, Aššur’s worship was doomed to remain a local affair throughout the rest of its history, never again to vie for the position of supreme god. Votive offerings to Aššur and his wife continued to be made in the Aramaic language up until the 2nd century CE, some eight centuries after the collapse of the Assyrian Empire—a testament to the resilience of the god’s cult. However, the sources fell silent afterwards. Following a life of more than two millennia, Aššur slowly slipped out of the Assyrians’ prayers as they slowly embraced a new universal god, the Christian God.

Olivier Goossens

Bibliography

- Andrae, W., Die archaischen Ischtar-Tempel in Aššur, 1922, Leipzig.

- Bär, J., Die älteren Ischtar-Tempel in Aššur. Stratigraphie, Architektur und Funde eines altorientalischen Heiligtums von der zweiten Hälfte 3. Jahrtausends bis zur Mitte des 2. Jahrtausends v. Chr., 2003, Saarbrücken.

- Borger, R., Die Inschriften Asarhaddons, Königs von Assyrien, 1956, Graz.

- Frahm, E., Assyria: The Rise of Fall of the World’s First Empire, 2023, London.

- Grayson, A., Assyrian Rulers of the Third and Second Millennia BCE (to 1115 BC), Toronto-Buffalo-London, 1987.

- Haller, A. & Andrae W., Die Heiligtümer des Gottes Aššur und der Sin-Šamaš-Tempel in Aššur, 1955, Berlin.

- Kryszat, G., “Ilu-šuma und der Gott aus dem Brunnen”, Vom Alten Orient zum Alten Testament. Festschrift für Wolfram Freiherr von Soden zum 85. Geburtstag am 19. June 1993, Kevelaer/Neukirchen-Vluyn, 1995, pp. 201-213.

- Lambert, W., “The God Aššur”, Iraq, Vol. 54, 1983, pp. 82-86.

- Larsen, M. The Old Assyrian City-State and its Colonies, 1976, Copenhagen.

- Maul, S., “Assyrian Religion”, A Companion to Assyria, ed. E. Frahm, 2017, Malden, pp. 336-358.

- Maul, S., “Die tägliche Speisung des Aššur (ginā’u) und deren politische Bedeutung”, Assyriologique Internationale in Barcelona, eds. L. Feliu & alia, 2013, Winona Lake, pp. 561-574.

- Radner, K., Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction, 2015, Oxford.

- Schroeder, O., Keilschrifttexte aus Aššur historischen Inhalts, Leipzig, 1922.

- Seux, M., Épithètes royales akkadiennes et sumériennes, Paris, 1967.

- Valk, Jonathan (May 2018). Assyrian Collective Identity in the Second Millennium BCE: A Social Categories Approach -dissertation (PDF). New York University.

- Andrae 1922; Bär 2003. ↩︎

- Haller & Andrae 1955, 9-ff., 12-ff.; Bär 1999, 10-ff. ↩︎

- Maud 2017, 336-337. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- Maud 2017, 339. ↩︎

- Tallqvist 1932; Lambert 1983; Radner 2015, 11. ↩︎

- Schroeder 1922, No. 54. ↩︎

- Andrae 1977, 174-176; Heinrich 1982, 215-217; Eickhoff 1985, 27-35. ↩︎

- Radner 2015, 11. ↩︎

- Andrae 1931; Kryszat 1995. ↩︎

- Valk 2018, 127. ↩︎

- Radner 2015, 13. ↩︎

- Seux 1967, 295ff. ↩︎

- Maul 2017, 342. ↩︎

- Frahm 2023, 41. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 42. ↩︎

- For Akkadian empire cf. the Stele of Naram-Sîn. ↩︎

- Frahm 2023, 42-43. ↩︎

- Larsen 1976, No. 37. ↩︎

- Maul 2017, 341. ↩︎

- Dagan: Grayson 1987, A.0.31. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 342. ↩︎

- Green & Black 1992, 38. ↩︎

- Maul 2013. ↩︎

- Borger 1956, 99. ↩︎

- Maul 2017, 343-344. ↩︎

- Frahm 2023, 227. ↩︎

- Ibidem, 230. ↩︎

Leave a comment