History is replete with mighty fortifications, with cities such as Constantinople and Diyarbakir boasting defensive walls that are rightfully seen marvels of engineering and architecture. And yet, this would not be the limit of wall construction, as some powers deemed that entire regions, not just cities, would benefit from their presence. Hadrian’s Wall, which separated Roman Britannia from the Caledonian tribes to the north, is one of the most famous examples of such a project. With a length of almost 120km and sitting at the heart of a sophisticated network of forts and watch towers, it has been deemed to function as both a defensive system but also as a customs post and trade management system, stamping Roman authority into the very landscape.

And yet there is another defensive wall, located in northern Iran, which utterly dwarfs Hadrian’s Wall, known as the Great Wall of Gorgan. Although it may not enjoy the same repute as its Roman counterpart, it has been labelled as one of the most sophisticated and ambitious frontier walls ever built and arguably the largest single defensive wall in history. This article will analyse the historical circumstances surrounding the wall before delving into how the Sassanians constructed and operated this impressive system of defences. Finally, we will dive into the reasons as to why the wall was built in the first place.

A Barrier Between Two Worlds

Before delving into the specifics of the Gorgan Wall, it is important to understand the geographic context in which it stood.

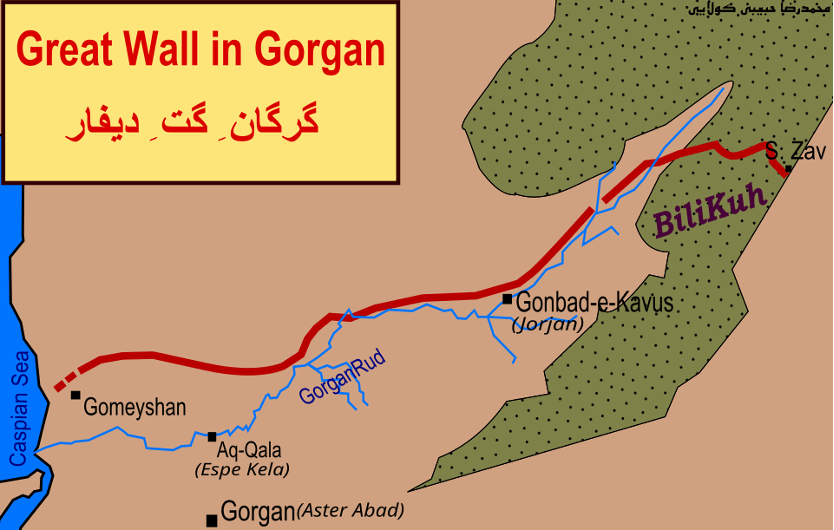

The wall lies in the Golestan province of northern Iran, a region known as Hyrcania in the ancient world, near the modern city of Gorgan, from which it takes its name. It begins on the shores of the Caspian Sea, turns north above the city of Gonbad-e-Kavus, and ends in the Pishkamar Mountains, a journey of some 195 kilometres that crosses a range of landscapes, from fertile plains to harsher, more arid terrain.

“It would be the colour of these brick, or the materials used to make them, that would give the wall a reddish hue, prompting the Turkmen to name the structure Qizil Alan, or the Red Snake.”

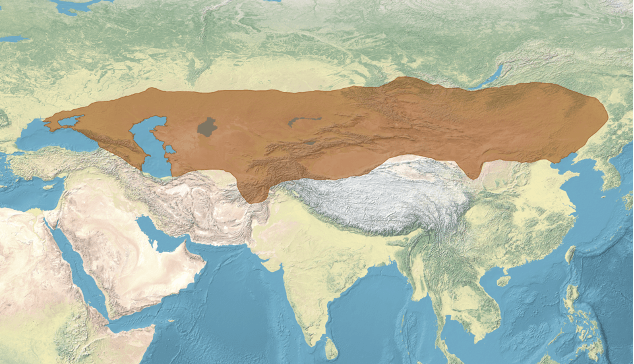

Just as the Gorgan Wall marked a transition between two physical regions, it also stood at a cultural and political frontier. To the south lay the settled agricultural lands of Hyrcania, while to the north stretched the more austere expanses of the Eurasian steppe. These northern lands were home to tribal confederations such as the Huns and early Turkic groups, whose nomadic way of life had developed over millennia to help them endure and thrive in this demanding environment.

With such a vast scale to cover and such a variety of geographic factors to manage, constructing the Great Wall would be, in all senses of the term, a monumental challenge for the King of Kings’ architects to overcome.

Building the Wall

The Sassanians were no strangers to monumental architecture, as can be seen in the wondrous monuments like the Arch of Ctesiphon and the royal complex of Takht-e-Soleyman. The Great Wall of Gorgan, however, would be a far greater challenge, both due to the amount of material required for its construction as well as the logistical challenges presented.

The wall was constructed using vast amounts of fired bricks, as the clay needed was more plentiful than stone in the landscapes that the Wall crossed. It would be the colour of these brick, or the materials used to make them, that would give the wall a reddish hue, prompting the Turkmen to name the structure Qizil Alan, or the Red Snake.

Remarkably, all the bricks were made at a standardized size of around 40x40x10cm. In order to produce the millions of bricks required for not only the wall and its accompanying fort network, the Sassanians constructed a vast network of standardized kilns that shadowed the course of the wall. Fieldwork conducted near one of the forts found seven kilns within a span of 220 meters, hinting at the presence of thousands of kilns along the entire wall. Archaeologists also discovered a vast canal system that brought water from either the Gorgan river or from nearby underground qanat systems. This would have been used for both supplying the workers and soldiers at the wall but also aiding in the manufacture of the bricks used in the wall’s construction, which required water to help mix and bind the clay before it was fired in the kilns. The addressing of these two requirements was made even more crucial as much of the wall runs through arid terrain that could not have met the network’s water requirements. The canal also fed water into a 5 meter ditch that was constructed along the north side of the wall. Although it was originally thought that this ditch was primarily a defensive moat, field studies found that the ditch, as well as the wall, ran along a natural gradient that would have allowed water to flow in an east-west direction without much trouble, indicating that it would have also likely aided in the shipping of materials along the wall.

“Fieldwork conducted near one of the forts found seven kilns within a span of 220 meters, hinting at the presence of thousands of kilns along the entire wall”

The construction of the Great Wall of Gorgan stands as a clear testament of the engineering and logistical prowess of Sassanian Persia, as well as the vast resources that it had at its disposal. With the wall now built, however, it is time to turn to how the Great Wall of Gorgan functioned within the wider northern defensive network of the Sassanians.

Manning the Wall

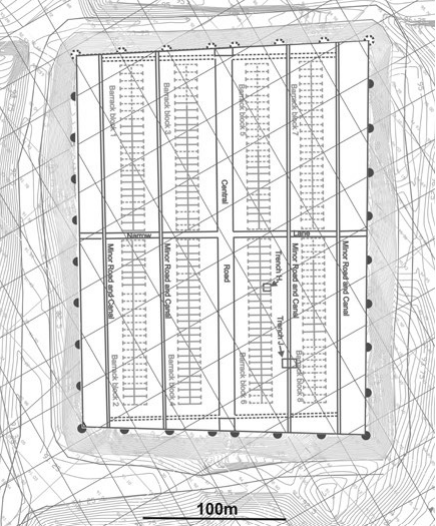

Although the wall, alongside its accompanying ditch/moat, would most certainly have been powerful obstacles to any attacking force from the north, it was further complemented by over thirty fortresses, with spacing ranging from 10 to 50km at strategic positions along the wall.

As with the wall itself, the fortresses were built of fired bricks, provided by the vast network of kilns and canals that were mentioned in the previous section. When it came to the internal buildings, which would have been less prone to attack, the Sassanians made use of less labour intensive but also less durable mud brick. These fortresses varied in size and shape but were most often designed in a rectangular shape, with neat rows of long, parallel buildings that have been interpreted as the barrack blocks where the soldiers were billeted, in a similar fashion to Roman legionary forts. The number of barracks within seemed to follow a standard protocol depending on the fort’s size, with larger forts boasting 4 to 6 blocks while smaller ones had 1 to 2. This indicated that certain zones of the wall may have been seen as needing garrisons of different sizes. In addition, efficient and rapid response times seem to have been at the forefront of the Sassanian architect’s minds. All the barracks were aligned at right angles to the walls, reducing the walking time to the wall and allowing the soldiers stationed within to rapidly assume their stations in the event of an attack from the north. The effort invested in the organization of these forts, as well as in the materials used to build them, indicate that these would have been permanent garrisons and not ad-hoc dwellings for levies during times of crisis. Estimates based on the sizes of the forts place the number of soldiers manning the Great Wall of Gorgan at between 15,000 and 30,000. Taking into account the forts that also dotted the hinterland beyond the wall, alongside the likely presence of horses given the central role of cavalry in the Sassanian army, this raises a further issue: how to feed so many men and animals across such a vast expanse?

Although food may have been transported along the canals to various forts and housed within dedicated storehouses and storage pits, the soldiers’ food would be primarily provided by what was available in their forts’ hinterland. Local agriculture would have provided grains, fruit and vegetables while the pastoral raising of livestock, such as sheep, goats and cattle would have provided the bulk of the soldiers’ protein requirements. Wild animals like birds, gazelles and fish would have also been hunted to supplement their diet but appear far less frequently, indicating that they were more of an occasional treat than a guaranteed part of the Sassanian garrison menu.

“Estimates based on the sizes of the forts place the number of soldiers manning the Great Wall of Gorgan at between 15,000 and 30,000.”

With such an organizational system supporting this powerful military force, the Great Wall of Gorgan stood as a mighty display of Sassanian power, ready to meet any challenge that came its way. And yet, this forces one to ponder what would make one of the most powerful and sophisticated empires in antiquity decide that building and maintaining such a defensive network was necessary.

The Threat from the Steppe

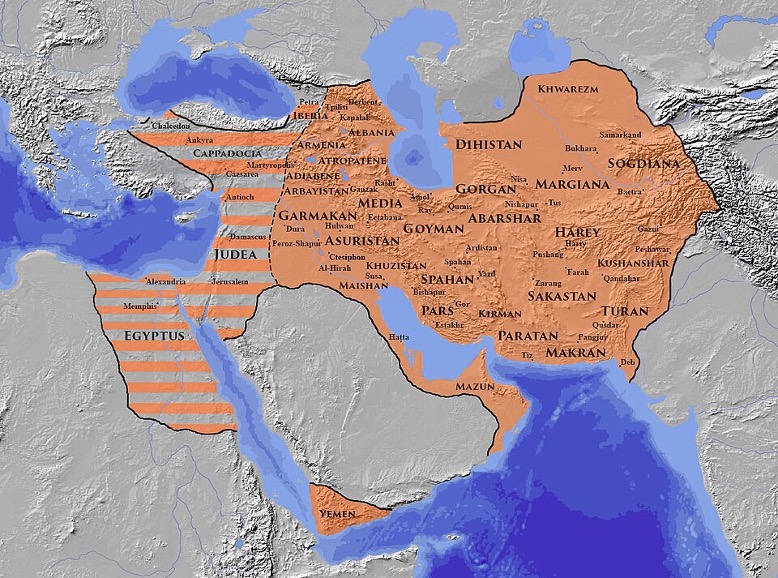

Although the Sassanian Empire is often remembered for its prolonged conflicts with Rome, it also faced serious and recurring threats along its eastern and northern frontiers, some of which posed existential dangers to the state.

As noted earlier, the Eurasian Steppe was home to a succession of nomadic groups which, at various points in history, coalesced into powerful confederations capable of threatening their settled neighbours. Among the most formidable of these were the Hephthalites, or “White Huns,” who established a powerful empire to the east of Sassanian territory during the fifth century. The Hephthalites inflicted several major defeats on the Sassanians, killing one of their kings and, at times, reduced them to tributary status. They even played a decisive role in internal Sassanian politics, supporting Kavad I in his successful return to the throne in 498 AD.

The eventual destruction of the Hephthalite Empire during the reign of Khosrow I Anushirvan, achieved through an alliance with the Göktürk confederation to the north, did not eliminate the steppe threat. Instead, it ushered in a new geopolitical reality, as the Göktürks themselves emerged as the dominant nomadic power on the empire’s northern frontier.

In this context, the geography of the Gorgan Plain assumed particular strategic importance. The relatively flat corridor between the Pishkamar Mountains and the Caspian Sea provided a natural route between the Eurasian Steppe and the Iranian heartland. This passage had been exploited by earlier powers, including the Parthians, and would be used again in later centuries by nomadic conquerors. By investing enormous resources into the construction of the Great Wall of Gorgan, the Sassanians sought to control and defend one of the most vulnerable approaches into their empire.

While the wall cannot be seen as an impenetrable barrier, it likely functioned as a means of deterrence, surveillance, and control, allowing the Sassanians to regulate movement across the frontier and respond rapidly to incursions. In doing so, it, alongside other great fortifications, such as in the Caucasus and the Hindu Kush, reduced pressure along the northern frontier and enabled the empire to concentrate military resources on other theatres, including its long-running conflict with Rome.

The Red Snake Quietly Fades

Despite the sheer scale of the Great Wall of Gorgan and the effort required to build, maintain, and operate it, the monument does not appear in any literary source identified to date. This absence makes understanding the reasons for the abandonment of one of the most ambitious defensive structures of Late Antiquity particularly challenging and places greater reliance on archaeological evidence.

The Great Wall of Gorgan was most likely abandoned as a result of a combination of environmental and human factors. Archaeological survey has demonstrated the existence of extensive canal systems and irrigated landscapes associated with the wall, supplying both its garrisons and the civilian settlements that supported them. Shifting river courses, declining water availability, or the failure of these hydraulic systems may have undermined both agriculture and supply, contributing to the gradual abandonment of settlements in the region.

“Despite the sheer scale of the Great Wall of Gorgan and the effort required to build, maintain, and operate it, the monument does not appear in any literary source identified to date.”

Excavations and radiocarbon dating indicate that the fortresses along the wall ceased to be occupied by the first half of the seventh century CE. By this point, the Sassanian Empire was under severe strain, having expended substantial military and economic resources during prolonged conflicts with the Roman Empire. It is therefore plausible that attention and resources were increasingly concentrated on more immediate threats elsewhere. The subsequent rise of the Islamic Caliphate and the rapid collapse of Sassanian authority likely accelerated the abandonment of the Gorgan frontier, removing any remaining capacity to maintain its defenses.

Once the frontier was no longer actively manned, the Great Wall of Gorgan quietly faded from the world. Its structures were plundered for building material in nearby settlements, while other sections were subsumed by the advancing Caspian Sea. One consequence of this slow disappearance was that, when new peoples moved into the region and encountered the wall’s ruins, its origins were no longer known with certainty. Attempts to explain it gave rise to a variety of names, from the aforementioned Red Snake to Sadd-i Iskandar, or Alexander’s Barrier, reflecting a legend that attributed its construction to Alexander the Great, who had died centuries before the wall was actually built.

A Wonder For The Ages

In its ambition, complexity and size, the Great Wall of Gorgan stands among the most extraordinary frontier systems of the ancient world. Conceived not as a single barrier but as a living landscape of walls, forts, canals, and garrisons, it embodied the Sassanian Empire’s determination to control movement between the steppe and the settled lands of Iran. Like Hadrian’s Wall or the great fortifications of northern China, it was as much a statement of imperial authority as it was a military defence, reshaping the land itself to serve the needs of empire.

Yet unlike its better-known counterparts, the Red Snake slipped quietly from memory. Its absence from written sources and its slow erosion by time and water ensured that its story would only be recovered through archaeology. Today, as research continues to reveal the sophistication of its construction and the complexity of the society that sustained it, the Great Wall of Gorgan demands recognition not as a forgotten curiosity, but as a central monument of Late Antiquity, one that reminds us that the frontiers of the ancient world were not static lines, but dynamic zones where geography, military power and human ingenuity mingled.

Milo Reddaway

Further Reading

- Khorramrouei, R., Pahlavan, P., Asgari, E.Z., Sabouri, S., Daneshi, P. and Shahri, P.S.K., 2020. Gorgan City: Heritage and Ritual Landscapes. Journal of Art & Civilization of the Orient, 8(28), pp.15-26.

- Mashkour, M., Khazaeli, R., Fathi, H., Amiri, S., Decruyenaere, D., Mohaseb, A., Davoudi, H., Sheikhi, S. and Sauer, E.W., 2017. Animal exploitation and subsistence on the borders of the Sassanian Empire: from the Gorgan Wall (Iran) to the gates of the Alans (Georgia). Sassanian Persia: Between Rome and Steppes of Eurasia, pp.74-98.

- Nokandeh, J., Sauer, E.W., Rekavandi, H.O., Wilkinson, T., Abbasi, G.A., Schweninger, J.L., Mahmoudi, M., Parker, D., Fattahi, M., Usher-Wilson, L.S. and Ershadi, M., 2006. Linear barriers of northern Iran: the great wall of Gorgan and the wall of Tammishe. Iran, 44(1), pp.121-173.

- Rekavandi, H.O., Sauer, E.W., Wilkinson, T., Tamak, E.S., Ainslie, R., Mahmoudi, M., Griffiths, S., Ershadi, M., Van Rensburg, J.J., Fattahi, M. and Ratcliffe, J., 2007. An imperial frontier of the Sassanian Empire: further fieldwork at the great wall of Gorgan. Iran, 45(1), pp.95-136.

- Rekavandi, H.O., Sauer, E.W., Wilkinson, T., Abbasi, G.A., Priestman, S., Tamak, E.S., Ainslie, R., Mahmoudi, M., Galiatsatos, N., Roustai, K. and Van Rensburg, J.J., 2008. Sassanian walls, hinterland fortresses and abandoned ancient irrigated landscapes: the 2007 season on the great wall of Gorgan and the wall of Tammishe. Iran, pp.151-178.

- Sauer, E., Rekavadi, H.O., Wilkinson, T. and Nokandeh, J., 2008. The enigma of the ‘Red Snake’: Revealing one of the World’s Greatest Frontier Walls. Current World Archaeology, (27), pp.12-22.

- Sauer, E.W., Nokandeh, J., Rekavandi, H.O., Naskidashvili, D., Nemati, M.R., Mousavinia, M., Otto, A., Herles, M. and Kaniuth, K., 2020, April. Interconnected frontiers: Trans-Caspian defensive networks of the Sassanian Empire. In Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: Vol. 2: Field Reports. Islamic Archaeology (pp. 363-372). Harrassowitz Verlag.

- Sauer, E.W., Rekavandi, H.O. and Nokandeh, J., 2020. The Gorgān Wall’s Garrison Revealed Via Satellite Search. New agendas in remote sensing and landscape archaeology in the Near East: studies in honour of Tony J. Wilkinson, p.80.

- Sauer, E.W., Nokandeh, J. and Omrani Rekavandi, H., 2022. Evolution of the Sassanian defences of the Gorgan Plain. Antiquité Tardive, 30, pp.103-118.

- Wilkinson, T.J., Rekavandi, H.O., Hopper, K., Priestman, S., Roustaei, K. and Galiatsatos, N., 2013. The landscapes of the Gorgān Wall. Persia’s Imperial Power in Late Antiquity: The Great Wall of Gorgān and Frontier Landscapes of Sassanian Iran, pp.24-132.

Leave a comment