Central Asia is home to a wide variety of cultures and languages that have interacted with each other over the centuries. Since antiquity, the Iranian languages have been prominent in this part of the world, their homeland being chiefly present-day Iran. The oldest representative of the Iranian branch, the Avestan language, is an East Iranian language and became an important liturgical language for Zoroastrians, as it is the language of Zarathustra’s Gathas. The Old Persian language, a West Iranian language and ancestor of modern Persian (i.e. Farsi, Dari, and Tadjik), was the language of the vast Persian Empire, which extended into Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. However, Old Persian was by no means used as the lingua franca of this enormous empire; that honour belonged to Aramaic, a specific variety that is today called Imperial Aramaic. Old Persian and its ad hoc invented cuneiform script were restricted to monumental inscriptions, often accompanied by Babylonian and Elamite versions. The first time an Iranian language was used in Persian administration was in the Parthian Empire, when the Middle Iranian Parthian language took centre stage (tellingly, it was written in a script derived from the Aramaic abjad). The subsequent Sassanian dynasty deployed the closely related Middle Persian Pahlavi dialect as an official and literary language. These languages were part of a Western Iranian continuum and were spoken by the ruling elite of the Persian Empire. After the conquest of Persia by the Arabs, Arabic became the dominant language for several centuries, until Classical Persian (an immediate descendant of Pahlavi) emerged.

In the east of the former Persian Empire, on the outskirts of the Islamic world, Arabic did not penetrate as a lingua franca, and the Islamization of the region took place only by the 10th century. The language that gained momentum there in the early Middle Ages was another Middle Iranian language, but from the Eastern branch. Here too, there was a continuum of dialects that were often restricted to a specific region, such as Khotanese or Choresmian. But it was Sogdian, a language originally spoken in the province of Sogdiana and the city of Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, that became the lingua franca of the Silk Road in that part of Central Asia. Turkic peoples such as the Uyghurs, whose native language differed greatly from Indo-European Sogdian, also used this language for administration. The Sogdians were known as industrious merchants, and it was through trade that they spread their language as far as western China, among other means by founding merchant colonies in Chinese Turkestan.

“But it was Sogdian, a language originally spoken in the province of Sogdiana and the city of Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, that became the lingua franca of the Silk Road in that part of Central Asia”

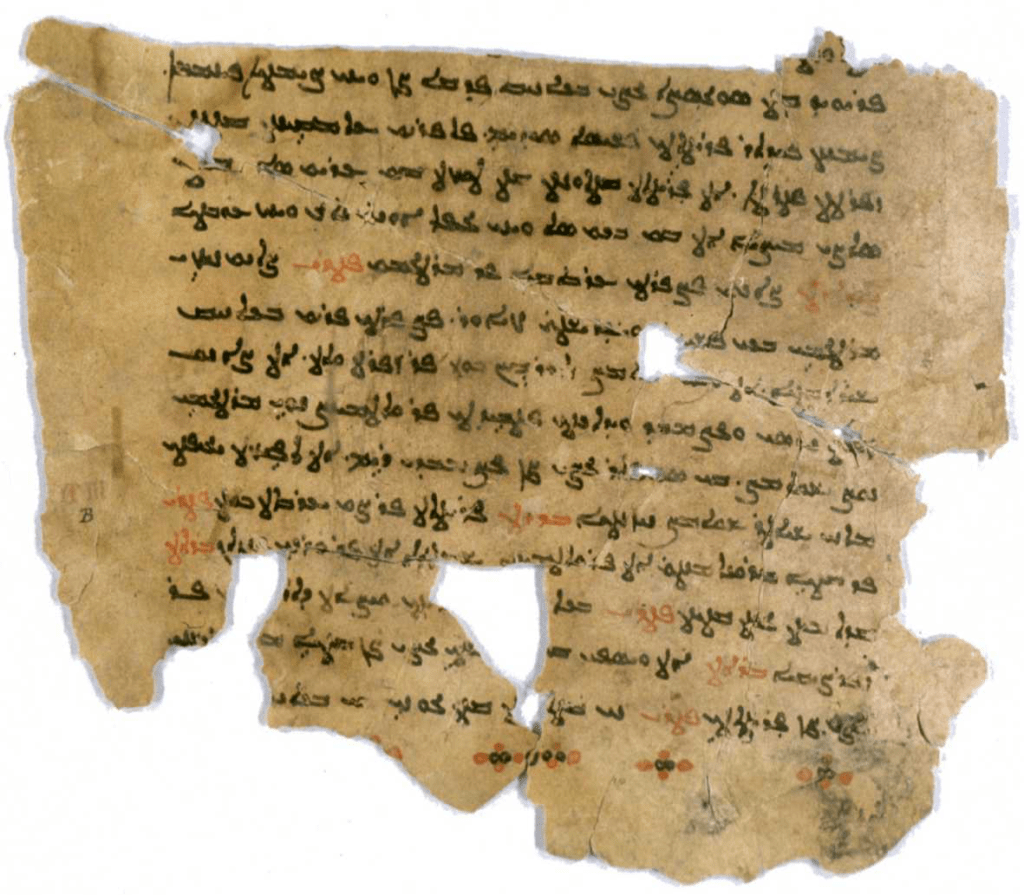

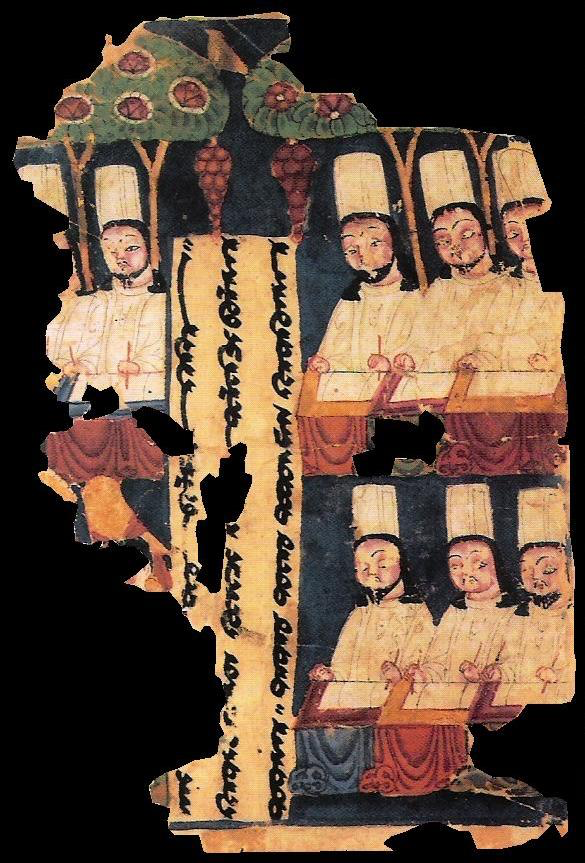

The oldest datable documents hark back to the fourth century, but the bulk of the Sogdian evidence dates to the early Middle Ages. The entire body of Sogdian writings is typically classified into three corpora according to the religious content of the texts: Buddhist Sogdian, Manichaean Sogdian, and Christian Sogdian. Furthermore, each corpus is characterized by its own linguistic peculiarities. These are most evident in the use of certain loanwords. For instance, Buddhist Sogdian texts are prone to using Sanskrit or Chinese loanwords, whereas Christian Sogdian employs more Syriac terms. In addition to these linguistic elements, the three varieties are also distinguished by their scripts (Sogdian, Manichaean, and Syriac). All of these scripts ultimately derive from the Aramaic–Syriac alphabet. This threefold division is mirrored in textbooks, grammars, and dictionaries of Sogdian, which typically focus on one of these varieties.

By far the largest corpus is the Buddhist Sogdian one. Like Tocharian, on which I wrote another blog (https://alongthesilkroad.com/2025/05/12/the-tocharians-their-language-and-literature/), these texts typically consist of translations of Indian or Chinese material, such as Jatakas (“birth tales”). In addition, most texts have been found in Turfan, where the Tocharian manuscripts were also discovered. On a related note, it is quite probable that Sogdians and Tocharians came into contact with each other early in their history, as suggested by the numerous Iranian loanwords in Tocharian, possibly from Proto-Sogdian. The script used in the Buddhist texts is called Sogdian-Uyghur, as it was a variant or precursor of the alphabet later used for the Uyghur language. The smaller corpus of Christian Sogdian writings consists almost entirely of translations from Syriac works, written in the standard Syriac (Nestorian) alphabet. Some of these New Testament translations are accompanied by the Syriac text (as I noted in this post on bilingual New Testament manuscripts: https://alongthesilkroad.com/2025/09/12/the-beauty-and-value-of-eastern-bilingual-manuscripts-of-the-bible/).

“The entire body of Sogdian writings is typically classified into three corpora according to the religious content of the texts: Buddhist Sogdian, Manichaean Sogdian, and Christian Sogdian”

Linguistically, Sogdian attests a rather conservative nominal system, preserving much of the ancient Iranian case system. The verbal system, by contrast, has been innovated and expanded. Today, Sogdian survives as a living language, spoken by a relatively small community in modern-day Tajikistan. This “Neo-Sogdian” is called Yaghnobi and preserves some characteristic features of ancient Sogdian, while innovating in certain respects like other modern Iranian languages.

If you want to learn Sogdian, you can turn to a few handbooks. The best and most easily accessible is Skjærvø’s PDF course on Manichaean Sogdian. Skjærvø, one of the world’s leading experts on Iranian languages, teaches the basics of the Manichaean variety there, and it is available for free. A comprehensive manual covering all varieties of Sogdian was published as recently as 2022 by the Japanese scholar Yoshida Yutaka, but unfortunately only in Japanese (ソグド語文法講義 [Lectures on Sogdian Grammar]). Even without an English translation, this work is a milestone in Sogdian studies and has been very positively received.

Maxime Maleux

References

- Catt, Adam Alvah. 2023. ‘Review of Yoshida Yutaka 吉田豊 2022. Sogudogo bunpō kōgi ソグド語文法講義 [Lectures on Sogdian Grammar]’. Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 76(1): 165–167.

- Fortson, Benjamin W. 2011. Indo-European language and culture: An introduction. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor. 2007. An Introduction to Manichean Sogdian. Berlin.

- Yoshida, Yutaka. 2016. “SOGDIAN LANGUAGE i. Description.” Encyclopaedia Iranica. Published November 11. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sogdian-language-01/

Leave a comment