“Through textiles and texts alike, Astana reveals the rich tapestry of a world once connected by fibre, faith, and far-reaching ambition.”

The Silk Road, a vast commercial network connecting Eastern China to the Mediterranean, was more than just a route for trade – it was a crucible of exchange, where ideas, materials, and cultures intersected for centuries. Stretching from the imperial capitals of the East to the ports of the West, it carried not only spices, paper, leather, and tea but also textiles, literature, religious beliefs, and technologies. While much of the Silk Road’s history was long shrouded in legend and fragmented historical texts, modern archaeology has brought greater clarity to its narrative. One of the most illuminating discoveries in this regard is the Astana Graveyard, located near the ancient Turfan Oasis in China’s Xinjiang region. The artifacts unearthed there have significantly expanded our understanding of Silk Road commerce, mobility, and material culture.

Turfan was an important node in the Silk Road network due to its geography. Strategically located between the Taklamakan Desert and the Tianshan Mountains, it served as a crucial oasis where traders could rest, replenish, and engage in commerce. From Turfan, the route extended westward through the Fergana Valley into Osh (modern Kyrgyzstan), and then into the mountainous corridors of present-day Northern Pakistan, including Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Upper Chitral. Along this corridor, textile traditions evolved through layered influences, as Chinese silk culture merged with Central Asian wool craftsmanship and South Asian dyeing techniques.

Set against the harsh, arid backdrop of the Turfan Oasis, the Astana Cemetery served as the burial ground for residents of the Gaochang Kingdom between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE. Its remarkable preservation – made possible by the region’s dry climate – has yielded textiles, manuscripts, wall paintings, and everyday objects that reflect the advanced nature of Silk Road society. Through these discoveries, archaeologists and historians have been able to piece together a far more nuanced picture of life along this ancient route. The Astana tombs function not merely as resting places for the dead but as time capsules of interregional exchange, material innovation, and social dynamics.

“The Astana tombs function not merely as resting places for the dead but as time capsules of interregional exchange, material innovation, and social dynamics.”

The textile heritage recovered from these graves provides critical insights into one of the Silk Road’s most economically and culturally significant industries: the trade and production of silk and wool. China, the original source of sericulture, had long monopolized the secrets of silk production. Prior to 500 CE, only Chinese craftsmen knew how to raise silkworms and spin fine silk threads. Even after this monopoly was broken by the Byzantines and Persians, Chinese weavers continued to produce some of the finest textiles known to antiquity. Silk, in fact, became so valuable during the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) that it was often used as a form of currency.

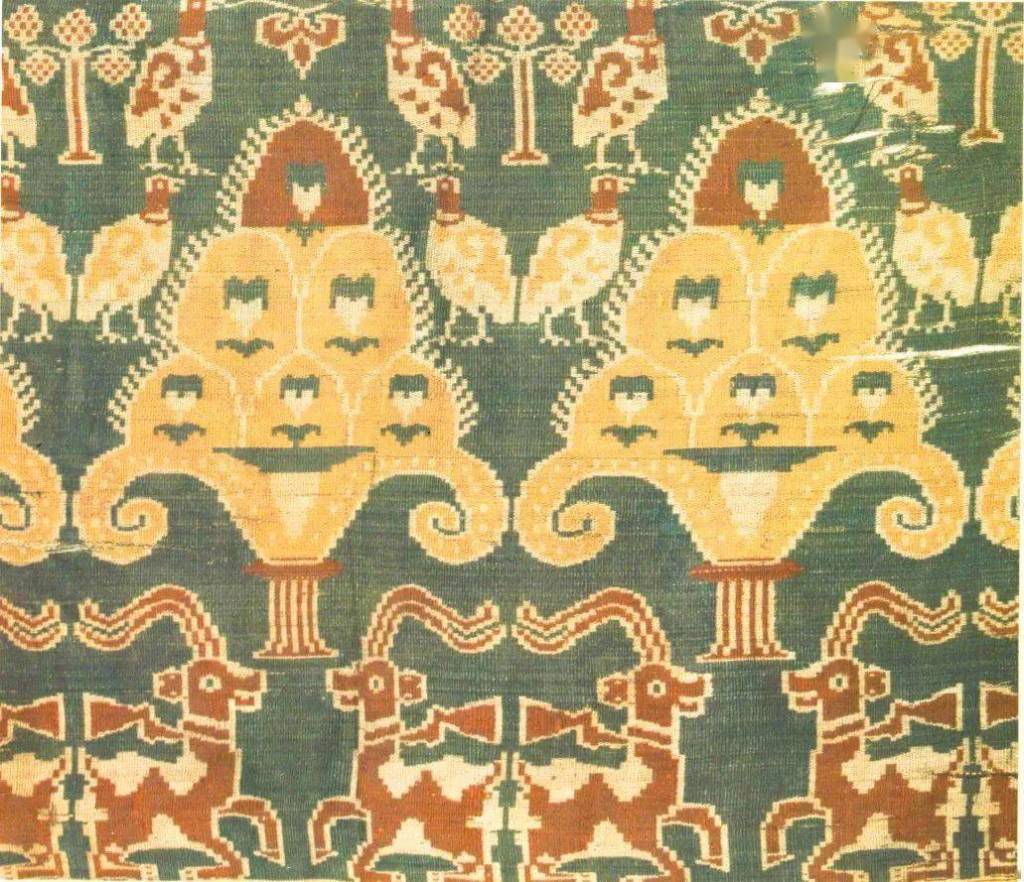

The finds at Astana confirm that the Silk Road facilitated the exchange of not only goods but also technical knowledge. Turfan itself was a melting pot of cultures, particularly during the 5th to 8th centuries, when it hosted two dominant immigrant communities: the Chinese and the Sogdians of Central Asia (modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan). The Sogdians played a crucial role in Silk Road trade and were instrumental in transmitting textile techniques across Eurasia. They brought with them wool tapestries, indigo-dyed cottons, and a sophisticated visual language of design motifs. Interestingly, although the Sogdians were prominent merchants, documents found in the Astana tombs reveal that they did not typically engage in the silk trade directly – perhaps indicating their niche in other commodities or intermediary roles in textile production.

The textiles preserved at Astana also highlight the impact of material availability on weaving traditions. The choice of silk or wool directly influenced the structure and aesthetics of the cloth. While silk’s tensile strength and long fibres allowed Chinese weavers to create complex warp-faced patterns and polychrome silks (known as jin Chinese), Central Asian artisans working with wool—a shorter, more elastic fibre—opted for weft-faced tapestry structures. These materials dictated weaving technologies and resulted in distinct textile traditions that still managed to influence one another through continuous cultural contact. One of the most striking examples of this exchange is the evolution of tapestry weaving.

“The choice of silk or wool directly influenced the structure and aesthetics of the cloth. While silk’s tensile strength and long fibres allowed Chinese weavers to create complex warp-faced patterns and polychrome silks (known as jin Chinese), Central Asian artisans working with wool—a shorter, more elastic fibre—opted for weft-faced tapestry structures.”

Sogdian artisans in Turfan introduced a technique using wool, which Chinese weavers adapted to silk, developing intricate designs that eventually culminated in the kesi or “carved silk” style of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1279 CE). These silk tapestries imitated the brushwork of calligraphers and painters representing a high point in the technical and artistic sophistication of Chinese textile production.

Beyond textiles, the Astana Graveyard has also provided documentary evidence that deepens our understanding of the political and economic networks of the Silk Road. Wooden slips, contracts, and letters recovered from the tombs reveal details about taxes, goods exchanged, and the bureaucratic workings of frontier regions. These documents highlight the social diversity of Silk Road participants: soldiers, scribes, merchants, artisans, and farmers whose lives were intimately tied to long-distance trade.

Finally, the discoveries of Astana illuminate the importance of loom technology in the transmission of weaving knowledge. Evidence suggests that Sogdian weavers in Turfan developed wide compound weave structures – likely using harness looms adapted from Iranian or Syrian designs. These looms allowed for the mechanical repetition of motifs and were far more efficient than earlier hand-operated models. The technological advancements made in Turfan would eventually ripple outwards, influencing weaving centres in Central Asia and Sichuan, where the famed shu jin or Sichuan brocades had already been thriving since the Han dynasty ruling from 206 BCE to 220 CE.

In conclusion, the archaeological discoveries at the Astana Graveyard are a cornerstone in Silk Road knowledge. They offer not only physical remnants of ancient trade but also compelling evidence of technological exchange, cross-cultural collaboration, and the everyday lives of those who shaped the Silk Road. Through textiles and texts alike, Astana reveals the rich tapestry of a world once connected by fibre, faith, and far-reaching ambition.

Bakhtawar Jamil

Bakhtawar Jamil graduated from the National College of Arts in Pakistan with a degree in textiles and a deep-rooted interest in art history, material culture, and heritage studies. Their practice as a textile practitioner is informed by a research-based approach that explores how indigenous craft traditions encode ecological knowledge, cultural identity, and community memory.

Further reading:

- Baumer, C., The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Silk Roads, 2014, London.

- Hansen, V., The Glory of the Silk Road: Art from Ancient China, 2004, New York.

Leave a comment