Anatolia is home to multiple obscure and lesser known languages. One of them is Galatian: a language spoken in central Anatolia between the 3rd century BCE and the 1st century CE by the Celts who migrated from Europe. It is important to note that Galatian is preserved in a highly fragmentary state. Until today no single monolingual Galatian source is attested.

This article will focus mainly on the linguistic aspects of Galatian. Its attestation and source material will be discussed as well as some conclusions that can be drawn from the limited corpus. Finally, the position of this language in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family will be addressed. The term ‘Celt’ is historically complex as it was shaped by modern nationalism and politics. In this paper, a distinction is made between archaeological, linguistic, and ethnic uses of this term. However, the focus remains linguistic.

“It is possible to compile a corpus of 100 unique Galatian words.”

It is possible to compile a corpus of 100 unique Galatian words. They are almost exclusively attested in Greek or Latin contexts. Of the total, 69%, appear solely in Greek sources, 13% only in Latin and 17% are found in both Greek and Latin material. A single name is attested in a Phrygian inscription. The majority, 47%, are attested in literary sources whilst 33% derive from epigraphic material and 2% from numismatic evidence. The majority of the inscriptions originated from Anatolia with 81% of them found in Galatia.

Each of these words is written in either the Greek or Latin alphabet; however, the transliteration of Galatian sounds does not appear to follow conventional standards. For example the Greek transliteration of the consonant /w/ could be written as <ou> (omicron + upsilon), <υ> (upsilon) or during the Roman Period as <β> (beta). In contrast, this is consistently written as <v> in Latin.

Unfortunately, the corpus only exists of names. Although the majority of these are personal names, ethnonyms, theonyms and toponyms also occur. Based on a comparison with other Celtic languages it appears that a large number of words in the corpus are compounds. This is a common strategy in Indo-European languages to form neologisms. It is possible to distinguish two types of compounds: endocentric and exocentric.

“Based on a comparison with other Celtic languages it appears that a large number of words in the corpus are compounds.”

In endocentric compounds the meaning comes from the sum of both word parts. An example is επο-ρηδο- (epo-rèdo); epo– from Proto-Celtic (PC) *ekwo– meaning horse and –rèdo- from PC *rēdo-, to drive/carriage. The compound either means ‘the horseback riding’ or ‘the driving in a chariot’.1

In exocentric compounds the meaning of the word cannot be obtained from the sum of both parts. They are often derived from an intrinsic quality of the thing they represent. An example of this is the name Κατο-μαρος (kato-maros). Kato– from PC *katu-, meaning ‘battle’ or ‘fight’, –maros from PC *māro-, ‘large’. The combination of both parts means something like ‘large in battle’, yet solely based on this, one could not comprehend its exact meaning.2

In general, some patterns can be discerned. When a name consists of two nouns, the word on position 1 (N1) determines the one on position 2 (N2). This may occur either as a possessive construction or as the object dependent of N2. These words are always endocentric compounds (cf. supra). An example of the first phenomenon is Αλβιο-ριξ (albio-rix), albio- from PC *albiyo- ‘world’ and -rix ‘king’, hence ‘king of the world’.3 The latter can be explained using the aforementioned επο-ρηδο- (epo-rèdo), with the horse functioning here as the object of the noun which means ‘the driving’, hence ‘the horseback riding’. In some attestation three nouns are combined. These three-part compounds behave the same way as two-part compounds. An example of this is επο-ρηδο-ριξ (epo-rèdo-rix), meaning ‘the king of horse driving’.

The combination of a noun and an adjective or the compound of an affix / suffix with an adjective always makes an exocentric compound. This is best demonstrated in Βηπο-λιτανός (vepo-litanos) vepo– from PC *wekw– ‘face’ or ‘speech’ and –litanos from PC *flitano– ‘broad’, meaning ‘broad of speech or face’ This compound displays an intrinsic quality of the represented word, yet without further context it remains impossible to determine its exact meaning.4 Another example is ἀτ-επό (at-epo). The word at is most likely a prefix from PC *ad, ‘towards’. In combination with epo it means something like ‘towards or belonging to the horse’. As in the previous examples its exact meaning is unknown from the sum of both words alone. One could possibly interpret it as a kind of stableman or an equestrian.5 A similar example is found in the Latin word essendum which is a Celtic loanword, probably Gallic. It is a compound made out of the prefix *es ‘in, inside’ and the verb *sed ‘to sit’. Literally, essendum means ‘a sit-in’ or less literal ‘a chariot’.6

“It is generally accepted that the Celtic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family.”

It is generally accepted that the Celtic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family, a group of languages all over the Eurasian continent which descent from one common ancestral language: proto-Indo-European. The Celtic languages’ most remarkable shared characteristic is the loss of the proto-Indo-European (PIE) /*p/ at the beginning (anlaut) or in the middle (inlaut) of a word. Furthermore, each PIE vowel remains preserved, except for PIE /*e/ which became a PC /*i/. The latter is most noticeable in the Galatian substantive rix ‘king’, as opposed to the Latin rex ‘king’.

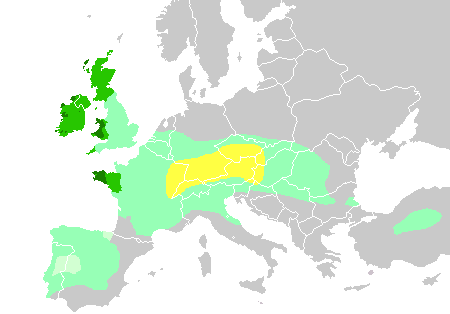

The Celtic languages’ subdivision within the Indo-European family tree remains a topic of considerable debate. This paper does not aim to provide an in-depth overview of this issue, as that would warrant a separate study altogether. Geographically, they could be subdivided into the languages spoken in mainland Europe and those on the British Isles. Another subdivision can be based on the consonant shift from PIE *kw to *p or *q. This grouping is controversial, however, as this sound evolution typologically often occurs. In addition, the shift probably happened at different times in the individual languages. An example of this is Gaulish where both sounds occur depending on the degree of archaism of the inscription.7

“Galatian appears to strongly resemble Gaulish and belongs to the Continental Celtic language group due to its linguistic and geographic similarities.”

Galatian appears to strongly resemble Gaulish and belongs to the Continental Celtic language group due to its linguistic and geographic similarities. It is unclear whether the two should really be seen as separate languages or just as dialects of the same tongue. The main differences between both is the occurrence of haplology (the omission of one occurrence of a sound or syllable that is repeated within a word, for example ‘probly’ for ‘probably’) in Galatian words and a presumably sound shift from /u/ to /o/. These could be the result of regional influences or the lack of a conventional script.

The Galatians and their language remain shrouded in mystery. At this moment there is little evidence to suggest that they spoke a language separate from Gaulish. The small corpus that has come down to us through Greek and Roman authors and epigraphic material gives some information on Galatian naming practices and compounds, but drawing further conclusions would be too optimistic with the current state of our knowledge.

Jelle Schelfthout

Jelle Schelfthout (born 2001) is an Archaeology Master’s student with a specialization in Egyptology at Ku Leuven from Leuven, Belgium. In 2023 he obtained a Master’s degree in Language and Literature, specializing in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. His interests are topics of death and identity in Akkadian and Egyptian literature, (Late-)Egyptian syntax and the transitions of power during the Third Intermediate Period. His current research focusses on the Osirian Chapels of the God’s Wives of Amun at Karnak. In his spare time he designs 3D reconstructions of Roman, Greek and Egyptian architecture. As of September 2025 he will give an introductory course to Middle-Egyptian for Egyptologica Vlaanderen.

Bibliography

- MacAulay, D., The Celtic Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, Cambridge.

- Matasović, R., Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic, Brill, 2009, Leiden.

- Stiffter, D., The Sound of Indo-European: Phonetics, Phonemics and Morphophonemics, 2012, Copenhagen.

- Uhlich, J., “Verbal governing Compounds (Synthetics) in Early Irish and other Celtic languages”, Transactions of the Philological Society, Vol. 100, 2002, pp. 403-433.

Leave a comment