From the 6th to the 4th centuries BCE, the Achaemenid Persian dynasty built one of the most extraordinary empires the world has ever seen. At its height, it stretched from the Balkans and Libya in the west to the steppes of Central Asia and the borders of India in the east. And yet, only decades after the empire was founded by Cyrus the Great, it would be plunged into crisis. Cambyses, Cyrus’s son and the conqueror of Egypt, was dead, having died while travelling to quell a rebellion supposedly led by his brother. Sources state that a priest named Gaumata had stolen the throne, pretending to be the king’s brother after having murdered him. This state of affairs was made all the worse by unrest growing in the provinces, meaning that the empire was coming dangerously close to falling apart soon after it had been created.

From this chaos would emerge one of history’s most remarkable rulers. Darius, a distant relative of Cyrus and former royal cup-bearer to Cambyses, overthrew Gaumata and crushed the revolts, becoming the new King of Kings. And yet it would be through far more than military force that Darius would hold the great empire together. Over the course of his reign, he introduced a series of administrative, economic, and ideological reforms that would not only stabilise Persia but help it prosper, shaping imperial governance for centuries to come.

Reprogramming the Machine of Governance

Even though Darius had slain the usurper Gaumata and avenged the murder of Cambyses and his brother, his troubles were only just beginning. Revolts soon broke out in Elam and Babylon, followed by uprisings in other parts of the empire, even in the Persian heartland. After two years of brutal campaigning, Darius secured his position as king, but long-term stability was still far from guaranteed. Recognizing that even an energetic and hands-on ruler could not be everywhere at once, Darius set himself to reshape how the empire was organised.

“Even though Darius had slain the usurper Gaumata and avenged the murder of Cambyses and his brother, his troubles were only just beginning”

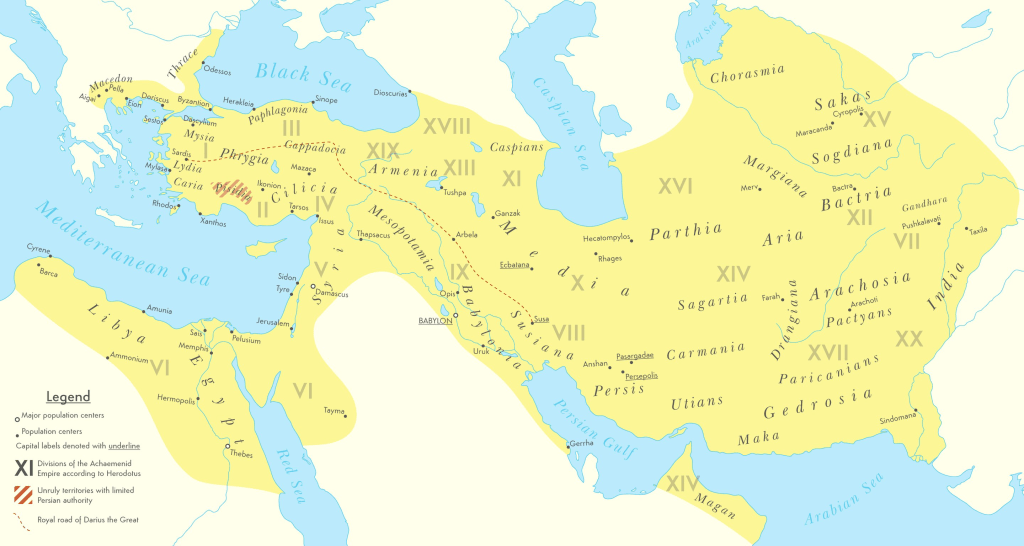

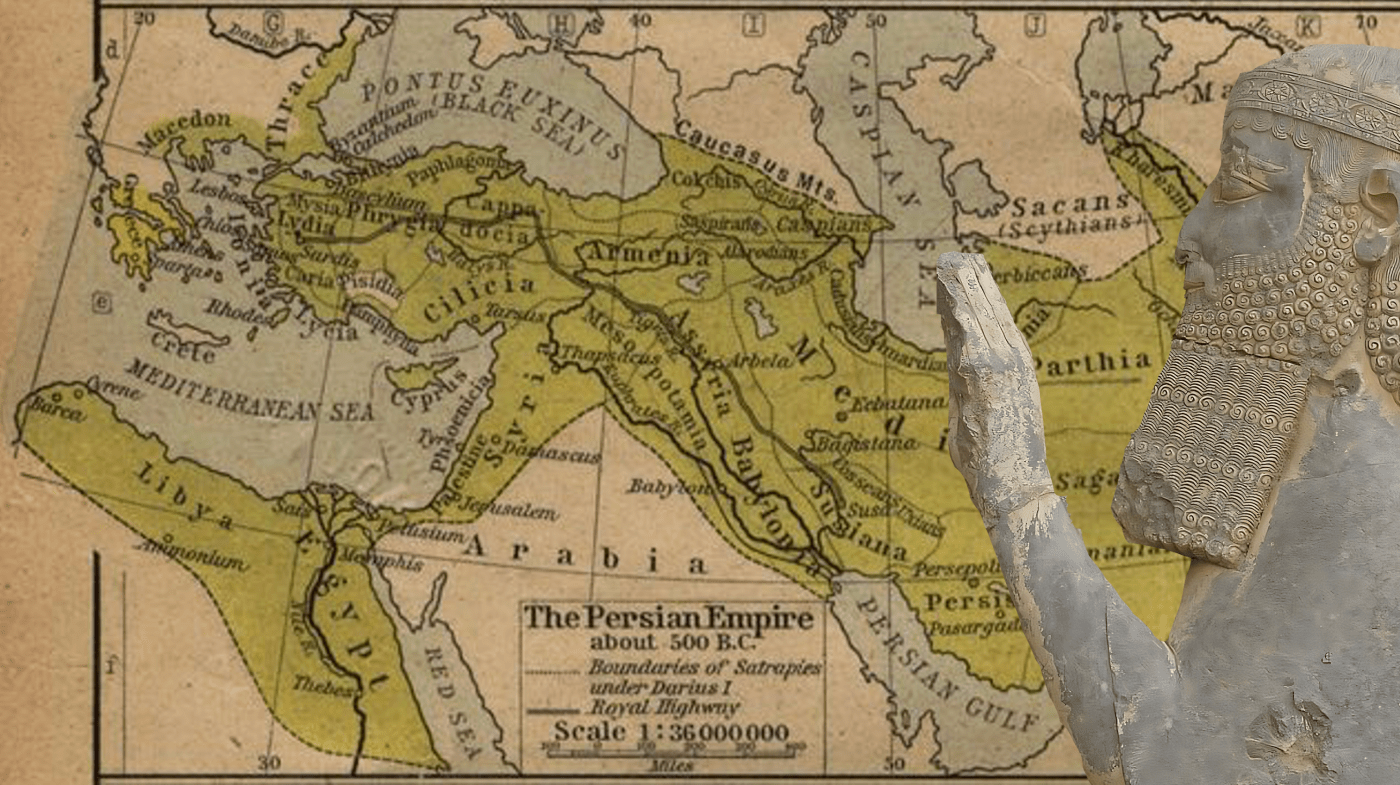

While Cyrus the Great had already created around 20 administrative divisions to help oversee the empire, Darius expanded the system, increasing the number of satrapies to 36. This allowed for more direct and efficient governance while limiting the power each satrap could amass, reducing the risk of political rebellion.

Satraps were charged with maintaining order, collecting taxes, and, during times of war, supplying troops to the royal army. Stationed in provincial capitals such as Marakanda (modern Samarkand) in the province of Sogdia, they were given a considerable amount of autonomy and managed both administrative and judicial affairs. To ensure effective local governance, satraps worked closely with regional elites, who were often familiar with existing traditions and religious customs. They also oversaw local military matters, acting as the first line of defence against both foreign invasions and internal unrest.

“Having already dealt with so many rebellions so early in his reign, Darius took steps to mitigate this issue by imposing multiple checks on satrapal power. “

Satraps were expected to emulate the royal court in style and procedure, projecting Darius’s presence to even the most remote corners of the empire. And yet, with such great autonomy inevitably came the risk of disloyalty, even rebellion. Having already dealt with so many rebellions so early in his reign, Darius took steps to mitigate this issue by imposing multiple checks on satrapal power. Satraps were required to consult the king on major matters, particularly those involving foreign affairs, and to maintain frequent correspondence with the royal court. Each satrap was also assigned a royal secretary to ensure they followed the king’s directives. Crucially, the heads of provincial finances and the military reported directly to the king, not the satrap, although the satrap could levy local forces if the situation demanded it. Additionally, inspectors known as the “Eyes of the King” travelled between provinces to conduct audits and report any misconduct.

Despite occasional uprisings, most notably the Great Satrap Revolt in Anatolia (372–362 BCE), the satrapal system proved remarkably effective. It enabled efficient governance across a vast and culturally diverse empire, helping to sustain Achaemenid rule for nearly two centuries. So successful was this model that it was later adopted by future states including the Seleucids and the Arab Caliphates.

Sustaining the Empire: Taxation, Coinage & Reform

Empires survive on wealth, from funding armies to sustaining the machinery of governance, and the Achaemenid Empire was no exception. When Darius took power, Persian administration relied largely on irregular tribute and gift-giving from subject peoples, with no fixed taxation system. Having restructured the empire around an expanded satrapal framework, Darius turned his attention to its economic foundations. His reforms would not only fund future campaigns and monumental construction, but also allow for tighter control, clearer oversight, and faster imperial response to regional issues.

By 519 BCE, a new taxation system had been implemented across the empire. Each satrapy was now assessed for its agricultural productivity, and its obligations were set accordingly. Payment was typically rendered in silver, and the tribute owed by each region became fixed, creating predictability for the imperial treasury and accountability for local governors.

One of Darius’s most significant innovations was the introduction of a standardised coinage system. Although coinage had originated in Lydia in the 7th century BCE, Darius issued the first imperial Persian currency: the gold daric (from the Old Persian word for golden), minted only at royal centres of authority such as Susa and Sardis. Bearing the image of the king, most commonly in a martial pose while wielding weapons such as a spear and bow, the daric functioned not just as money but as a guarantor of legitimacy and economic stability. It quickly gained international circulation, reaching as far as Celtic Europe, and was complemented by a silver coinage system (the siglos) for domestic use, such as when satraps hired mercenaries, although the siglos seems to have been mostly used in Asia Minor.

Alongside this, Darius introduced standard weights and measures, helping regulate market exchanges, reduce fraud, and build a unified commercial system across diverse regions.

These economic reforms underpinned a vast increase in imperial revenue and efficiency. According to Herodotus, the empire received 232.2 tonnes of silver annually in tribute, with an additional ten tonnes of gold paid by India.

“Through these reforms, Darius transformed imperial wealth from an ad hoc flow of gifts into a structured, enforceable, and scalable economic system.”

Through these reforms, Darius transformed imperial wealth from an ad hoc flow of gifts into a structured, enforceable, and scalable economic system. In doing so, he laid the fiscal foundations for an empire that could project power over thousands of miles and sustain itself for two hundred years. The daric and the silver tribute were more than just instruments of wealth. They were instruments of control, uniting a patchwork of peoples into a functioning imperial economy. Like the satrapal system, Darius’s economic policy exemplified his genius for building systems to support the state, a legacy that would influence imperial governance for generations to come.

Connecting a World Empire

Alongside expanding the satrapal network and reforming the imperial economy, Darius set himself to the task of transforming how the empire stayed connected. Trade, armies, and people had to be able to move efficiently across the colossal territories of the empire but more importantly, royal messengers had to deliver instructions with speed and precision to enact the king’s will and inform him of any developments.

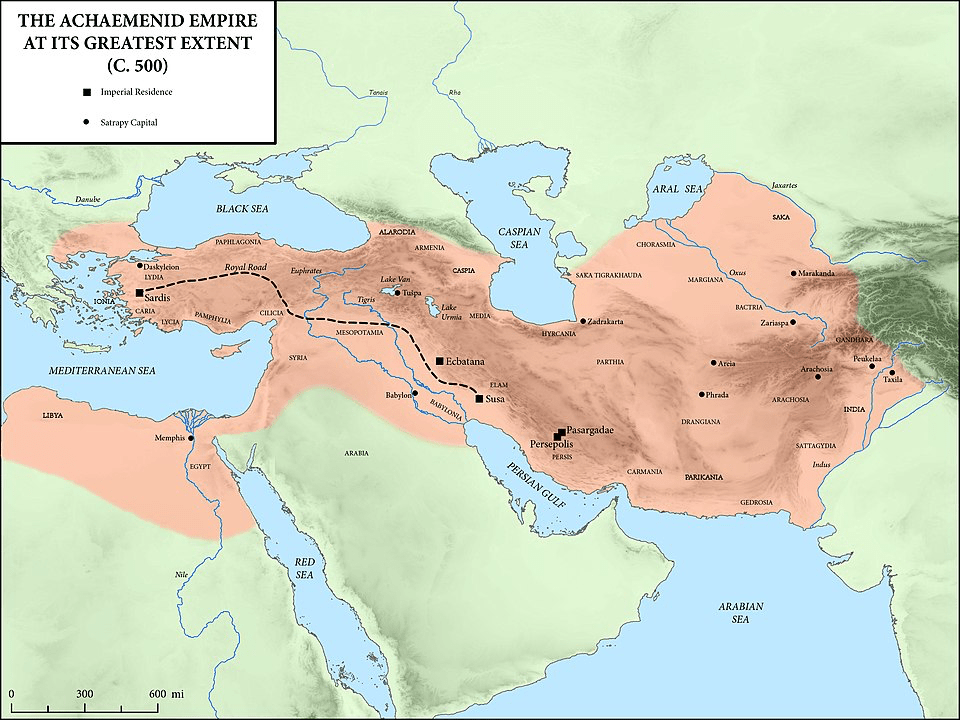

Previous Near Eastern states had built roads to address these needs, but what the Persians achieved under Darius was unprecedented in its time and would be seldom matched in the centuries to come. The most famous of these projects, the Royal Road, connected the western provinces to the Persian heartland. Stretching over 2,400 kilometres from Sardis in Anatolia to Susa, the royal capital in Elam, the road was flanked by similar highways linking Persia to its southern and eastern frontiers.

Way-stations, situated approximately every 28 kilometres, provided rest for travellers and shelter for imperial officials, while also serving as administrative points for road maintenance. Security was a high priority: outposts protected travellers and merchants, while severe penalties were enforced against bandits and robbers.

“The results of this new system were astonishing: while the 2,400-kilometre route from Sardis to Susa might take a traveller up to 90 days on foot, a royal message could complete the journey in just nine, a feat at which even the Greeks couldn’t help but marvel.”

Among the most important users of the Royal Road were the imperial couriers, or pirradazish. These messengers operated through a sophisticated relay system of post stations along the road that existed solely for their use, allowing the messenger to quickly switch to a fresh horse or to pass his message along to the next courier. The results of this new system were astonishing: while the 2,400-kilometre route from Sardis to Susa might take a traveller up to 90 days on foot, a royal message could complete the journey in just nine, a feat at which even the Greeks couldn’t help but marvel.

Darius’s infrastructure reforms did not stop on land. He also expanded the empire’s water transport capabilities, linking roads to rivers, canals, and ports. He ordered new waterways dug and existing channels connected to enable greater connectivity between the Nile, Red Sea, and Persian Gulf, a maritime strategy that anticipated the concept of the Suez Canal by over two millennia.

This combined land-and-sea network enabled the Persian Empire to operate at a scale unmatched in its day. Messages, goods, armies and royal orders could move at unprecedented speed, allowing Darius to respond swiftly to events in the provinces and maintain his authority over vast distances. His relentless investment in communication and transportation made him not only a regional monarch, but one of the first global rulers, whose logistical statecraft would later influence empires from Rome to the Mongols.

Enforcing the Rule of Law

“Says Darius the king: Within these countries what man was watchful, him who should be well esteemed I esteemed; who was an enemy, him who should be well punished I punished; by the grace of Ahuramazda these countries respected my laws; as it was commanded by me to them, so it was done”

– An extract from the Behistun Inscription, commissioned by Darius The Great.

Of all the domains Darius involved himself in, from infrastructure and economics to religious ideology, it was the administration of justice that seemed to particularly draw his interest. His inscriptions portray a ruler who took personal responsibility for justice and order, seeing them not merely as administrative necessities, but as divine mandates bestowed by Ahuramazda, the supreme god of the Zoroastrian faith to which he ascribed.

The Achaemenid Empire encompassed some of the oldest legal cultures in the world, including Babylonian, Elamite, and Egyptian traditions, and Darius would work to harmonise these diverse systems into a functioning imperial legal framework. He is recorded as having invited legal scholars from across the empire to codify and standardise existing laws, bringing them in line with imperial principles while preserving essential local customs.

“His inscriptions portray a ruler who took personal responsibility for justice and order, seeing them not merely as administrative necessities, but as divine mandates bestowed by Ahuramazda.”

The office of the Great King thus became a central pillar of the legal machinery of empire. Darius himself was the supreme judicial authority, with the power to intervene in complex or politically sensitive cases, although he would sometimes interest himself in more local cases as well. Provincial judges, often drawn from the Persian nobility and appointed directly by the king and his court, were expected to uphold these laws with integrity. In line with his broader administrative decentralisation, satraps were also empowered to oversee legal matters within their provinces, though their decisions could be reviewed or overturned by the king.

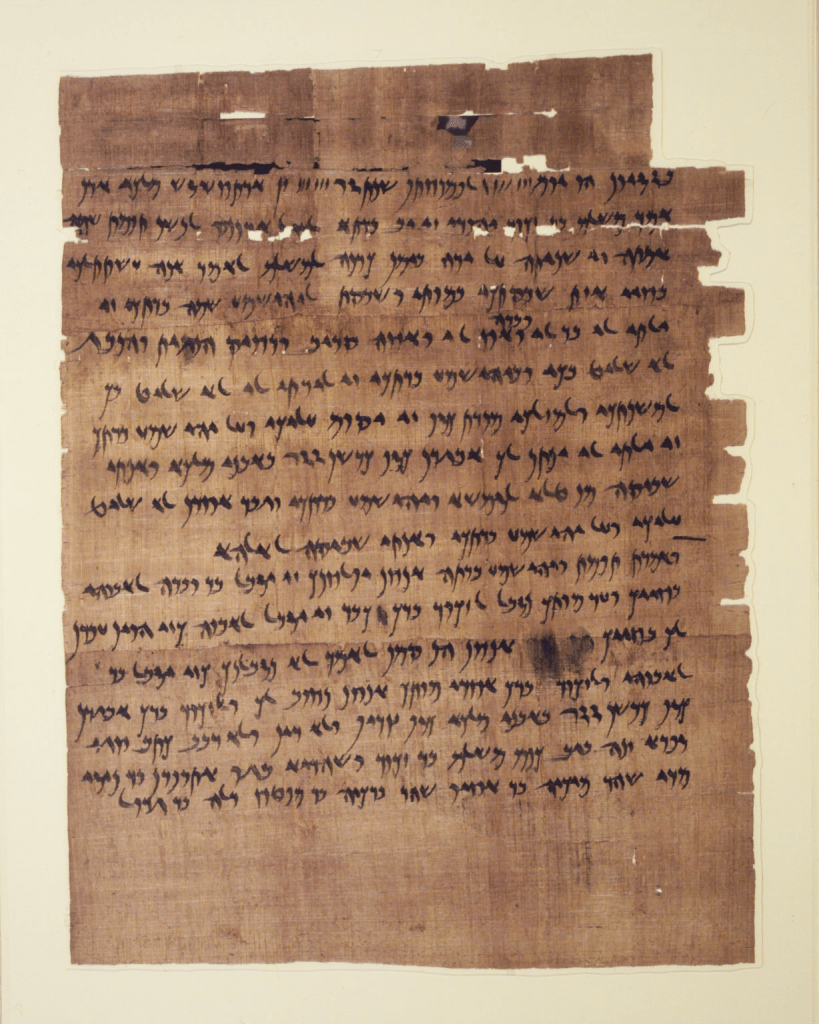

Language reform played a key role in these efforts. Darius promoted Imperial Aramaic as the administrative and legal lingua-franca of the empire. Used alongside local languages and cuneiform traditions, Aramaic helped bridge communication gaps across thousands of kilometres, much as Latin would later do in the Roman and medieval worlds. Its adoption allowed for greater consistency in record-keeping, legal communication, and the issuing of royal decrees.

The Persian commitment to written law is also reflected in the bureaucratic records uncovered at sites like Persepolis and Babylon. These clay tablets, often inscribed in Elamite or Aramaic, document everything from court proceedings to labour disputes, and show a surprisingly systematic and bureaucratic culture of justice. Legal decisions were archived for reference, reviewed by scribes, and sometimes escalated to higher levels of authority if the case demanded it, indicating a multi-tiered legal system responsive to both local and imperial needs.

It’s clear that Darius truly saw the rule of law as an expression of his imperial legitimacy, a core pillar of his divinely appointed mandate to rule and of the political identity of his empire. By combining regional legal traditions with imperial oversight and administrative clarity, Darius created a system that was both flexible and formidable, one capable of managing the legal complexities of a world empire. His efforts laid the groundwork for legal practices that would echo through later Hellenistic kingdoms, Persian dynasties and even the administrative systems of early Islamic caliphates.

The Ideology of Unity

The Persian Empire was a state of incredible religious and cultural diversity. Within its vast borders lived peoples whose traditions stretched back millennia such as the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Greeks, Jews, and many others, each with their own gods, customs, and laws. History has repeatedly shown that when diversity is mismanaged, it becomes a force that can destroy a nation. But one of the great achievements of the Achaemenid Empire was its deft handling of this delicate pluralism.

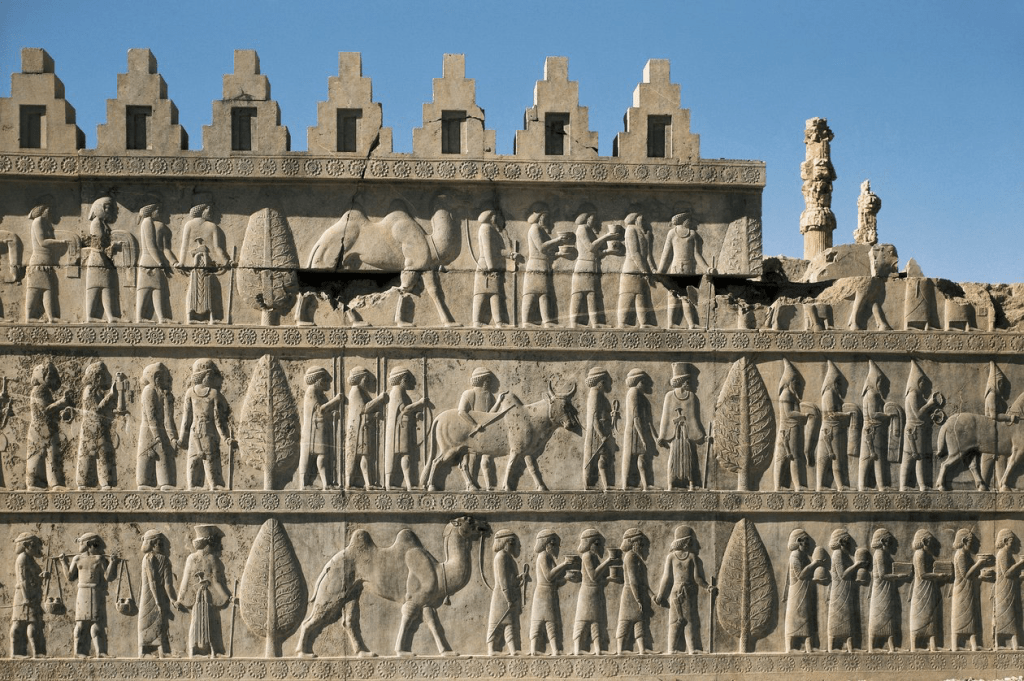

Darius the Great inherited a precedent of religious tolerance from Cyrus the Great, who had famously worked alongside local temples and priesthoods rather than against them. Darius not only maintained this approach but deepened it. In his inscriptions, he boasts of restoring temples across the empire and is even credited with funding the reconstruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. In Egypt, he presented himself as the rightful pharaoh and upholder of the local gods, a calculated act of cultural fluency to endear himself to this most ancient of cultures. He would promote this image in art as well, as can be seen in the great city of Persepolis, where dignitaries from various nations are shown in their cultural dress and treated with kindness and respect, not submission. For Darius, religious tolerance was not just benevolence, it was a tool for imperial stability, reducing the risk of unrest and ensuring that no sectarian grievance could threaten the unity of the empire.

“He forged a vision of unity through diversity that would echo across centuries of imperial history.”

Yet his approach to religion was not merely diplomatic. Darius’ world-view was deeply shaped by Zoroastrianism, a spiritual tradition that emphasised the cosmic struggle between Asha (truth and order) and Druj (falsehood and chaos). Throughout the Behistun Inscription and other texts, Darius repeatedly invokes Ahuramazda, crediting the god for his right to rule and for granting him victory over rebels who championed Druj. In this dualistic worldview, Darius positioned himself as the divinely mandated agent of order, rooting out chaos and restoring justice. His administrative reforms, from taxation and law to infrastructure and communication, were not just acts of governance; they were expressions of cosmic duty.

This fusion of tolerance and ideology, of pragmatism and spiritual vision, gave the Achaemenid Empire a uniquely resilient foundation. Darius did not seek to erase difference; he sought to frame it within a shared imperial order, bound together not by forced conversion, but by a unifying moral framework. In doing so, he crafted more than just an empire. He forged a vision of unity through diversity that would echo across centuries of imperial history.

A Great Legacy

Darius the Great, after nearly forty years of rule, died from an illness in 486 BCE. Although his inscriptions can still be read on stone cliffs and the walls of the palaces he constructed, his true legacy were the systems he built: in the logic of governance over chaos; in the flow of roads and coinage; in the idea that diversity could be managed without erasure; and that law could serve not just kings, but the empire as a whole.

By combining ruthless efficiency with administrative foresight and ideological nuance, he offered a blueprint that would echo through the Roman imperium, the Islamic caliphates, and even modern bureaucratic states. From local governors to tax systems, legal codes to post roads, many of the challenges faced by empires then remain familiar now.

In the end, Darius ruled not just with force, but with structure and diligence. He imagined an empire held together not by constant conquest, but by shared purpose and connected parts, a system vast enough to contain multitudes, yet cohesive enough to endure. Cyrus the Great may have brought the Persian Empire into being, and has been rightly celebrated as both a conqueror and a ruler. But it was Darius who made it a lasting, and incredible, success.

Milo Reddaway

Further Reading

- Briant, P., 2002. From Cyrus to Alexander: a History of the Persian Empire. Penn State Press.

- Dusinberre, E.R., 2013. Empire, Authority, and Autonomy in Achaemenid Anatolia. Cambridge University Press.

- Farrokh, K., 2007. Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War. New York: Osprey.

- Kuhrt, A., 2013. The Persian Empire: a Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period. Routledge.

- Llewellyn-Jones, L., 2022. Persians: The Age of the Great Kings. Hachette UK.

- Tobin-Dodd, R., 2019. Darius I in Egypt: Achaemenid Authority and Egyptian Continuity (Master’s thesis, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill).

Milo Reddaway holds a degree in Archaeology from Durham University, where his undergraduate thesis focused on the archaeological evidence for Achaemenid Persian governance and the empire’s renowned policy of religious tolerance. Raised in a diplomatic family, he spent much of his life travelling across the globe, an experience that fostered a lasting fascination with ancient cultures and historical sites. His Iranian heritage, through his mother, further shaped both his personal and academic interest in the history of the Near East, Central Asia, and the broader Iranian world. He has participated in several archaeological excavations, including at the Neo-Assyrian site of Tushhan (Ziyaret Tepe) in southeastern Turkey. He currently hosts Lorekindled, a podcast exploring topics from across the ancient and medieval worlds.

Leave a comment